A Growing Suburb

Sewers, Water, and Streetlights

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, April 2006

Between 1870 and 1920, West Hartford was transforming from a farm town to a suburban town. As it did, its government reacted by regulating construction and by building an infrastructure of bridges, sewers, water mains and paved roads. The population grew from about 1,500 residents who lived on farms, to 9,000 strong as housing developed in the center and along Farmington Avenue. The new, suburban citizens pushed for services that Hartford dwellers already enjoyed.

The Noah Webster House and West Hartford Historical Society archive holds many town records that describe these changes. One of them, Special Acts of the General Assembly, 1854-1913, provides a window into the infrastructure growth in town as well as the relationship between local and state governments. Annual Town Reports from 1870 also tell a story of how the town grew.

In 1888, when Hiram Hurlburt represented West Hartford, the General Assembly, established a Board of Health in each town. This Board of Health made rules that impacted the town budget and homeowners. It provided instructions for “privy, cesspools, drains and garbage.” This law lead to the town digging sewers. It also established rules for selling food. No carcasses of calf, pig or lamb could be sold here. It also required residents of town to report any cases of croup, scarlet fever, diphtheria, typhoid, typhus, cholera, or yellow fever. The state was ahead of federal regulations as it was not until 1906 that the U.S. Congress passed the Meat Inspection Act.

The growing population and hence the growing amount of sewage seeping into Trout Brook, led the General Assembly in 1893 to authorize the town of West Hartford to construct sewers. The town decided where the sewers would go and the local property owners had to pay for the spur that went to their home. They made a deal with Hartford to hook up to their system as well, and to pay Hartford a fee for the hook up. Developer Frederick C. Rockwell was West Hartford’s Representative to the General Assembly when this law was passed. Rockwell had some interest in these sewers as he built the first housing development in town on the Boulevard between Trout Brook and Main Street. He owned the land and began to build houses in the 1890s. After the sewers were built, the next step was, in 1913 to build a sewage disposal plant. In the same year the town got the power to grant building permits.

In 1895, the General Assembly made it the duty of the Hartford Board of Water Commissioners to lay connecting pipes and furnish water to the residents in West Hartford who applied and paid for their water. Hartford’s water came from the reservoir in West Hartford, so by-passed the town itself. Adolph Sternberg was West Hartford’s representative to the General Assembly at this time. He was one of nine children of Charles Sternberg, a German immigrant lawyer who, in 1854, came to West Hartford to farm.

In 1897, the General Assembly allowed for the town to appoint a Water Commission and establish building lines. It gave the town the power to lay pipes and ask property owners to pay for the pipes that went across their property.

In 1903, when Representative G. F. Scarborough sat in the General Assembly, the West Hartford town government got the power to build sidewalks, but at the property owners’ expense.

In 1907, Democrat Charles Edward Beach served the town at the General Assembly. Charles Edward was the son of Charles M. Beach, a Hartford businessman who bought land in West Hartford in 1859 and built Vine Hill Farm on the corner of New Britain Avenue and South Main. By 1900, Charles Edward managed the farm. He also was the town surveyor and served as selectman. As a representative at the State House, he helped establish a Special Commission to “inquire into the management of affairs” in town. It seems as though the town had a difficult time collecting taxes. Between 1888 and 1894 the tax collector books were missing. Beach, the only Democrat to serve between 1857 and 1925, seemed to be checking up on Republican politicians who controlled the town. Six years later, in 1913, the town established a Board of Finance to exercise supervision of financial affairs in the town.

The following table, which shows the growth in population, budget, and the allocation of funds within that budget, is a window into building the infrastructure of the town.

| Year | Population | Budget | Highways | Streetlights | Budget per person |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 1533 | $27,000 | 10% | 0% | $18 |

| 1880 | 1828 | $34,000 | 18% | 0% | $18 |

| 1890 | 1930 | $37,000 | 17% | 0% | $19 |

| 1900 | 3186 | $56,900 | 15% | 0% | $18 |

| 1910 | 4808 | $150,000 | 8% | 5% | $31 |

| 1920 | 8854 | $410,000 | 5% | 2% | $46 |

Over 50 years, the amount of money spent in town grew 15 times while the population grew 6 times. The percentage of budget money spent on highways and bridges peaked around 1890. The installation of streetlights occurred over a short period of time. Clearly by 1920, the town provided more services to its constituents.

One important piece of the infrastructure, education, became a larger percentage of the budget in the 1920s when seven schools were built: Beach Park, Morley, Smith, and Elmwood elementary schools, Plant and Talcott Junior Highs, and Hall High. After the town built up its infrastructure, it paved the way for more housing developments and attracted many new residents to enjoy the amenities of sewers, piped in water and street lights that had before, only existed in the city.

Biking in West Hartford

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, July 2012

In 2012, West Hartford’s Bicycle Advisory Committee meets the second Monday of every month to make West Hartford a more bike friendly town. Bike enthusiasts yearn for bike lanes and safe places to ride on the roads. Twentieth century plans for roads were all about cars; bicyclists are trying to change that.

West Hartford’s history as a bike town goes way back to the Charter Oak Race Track well before the “bike craze” of the 1890s. Back then, the bike craze led to athletic competitions, a new way to get to work, a new leisure time activity, and safer roads.

In September 1878, two Hartford physicians who purchased Columbia bikes proposed that the Charter Oak Race track add bicycle racing. In May 1879, the Hartford Courant reported that people were talking about a bicycle tournament at Charter Oak Park and that Hartford had some good bicycle riders ready to compete.

On June 13, 1879 George W. Pomroy of the Oakwood Hotel gave a purse of $100 [about $2,200 today] for a bicycle race at the Charter Oak Race Track. It was the best two out of three in mile heats. On the Fourth of July 1879, Charter Oak Park sponsored bicycle contests along with horse racing, and a sack race.

Mr. G.W. Pomroy at the Oakwood Hotel was particularly active in arranging the bicycle race. The crowd loved the race and pushed Pomroy to set up another race. According to the Courant, “The interest in bicycles is greatly on the increase in Hartford, since their manufacture has begun here at the Weed works, and many young men have become engaged in the use of the machine. A considerable number are very expert in its use, and with more entering a very entertaining race could be arranged.”

Albert A. Pope, who founded Boston’s Pope Manufacturing Company, became an enthusiast about bikes at the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition. He started to import bikes from England in 1878 and took out US patents on the European models. Col. Pope wanted bikes to be made in America and so he approached Hartford’s Weed Sewing Machine Company who used interchangeable parts and by the end of September 1878, they manufactured 50 bicycles with the large front wheel. To produce the Duplex Excelsior copies, Weed produced 77 unique parts and the only part that came from a supplier was the rubber tire.

Pope dubbed the new bicycle “Columbia.” His use of the hollow tube and ball bearings distinguished his bikes from others. According to an 1878 Hartford Courant article, “Mr. Pope… who resides ten miles from the city [Boston], rides to and from his place daily on one of these vehicles, unless the weather is stormy.” Further, the article stated that the bicycle craze in England had gone on for years and that an amateur rider had ridden a 3 minute 10 second mile.

By 1881, The Hartford Wheel Club organized monthly races at Charter Oak Park. On Saturday, June 25, 1881, at 3:00 pm, the amateur competitors biked from Capitol Avenue and Washington Street to the park. The 50 bicyclists, including five racers from New Britain were divided into three classes. It was the biggest gathering of bicyclists ever. The winning racer rode the mile in 3:25 from a standing start. The three judges included George B. Day, son of George Day the leader of the Weed Sewing Machine Company that was building the bicycles.

In the summer of 1882, Mr. Hyde of the Charter Oak Park Hotel and Mr. William B. Smith leased Charter Oak Park for the Fourth of July. They offered prizes worth $2,000 for trotting races, bicycle races and foot races. They offered a “shore dinner.”

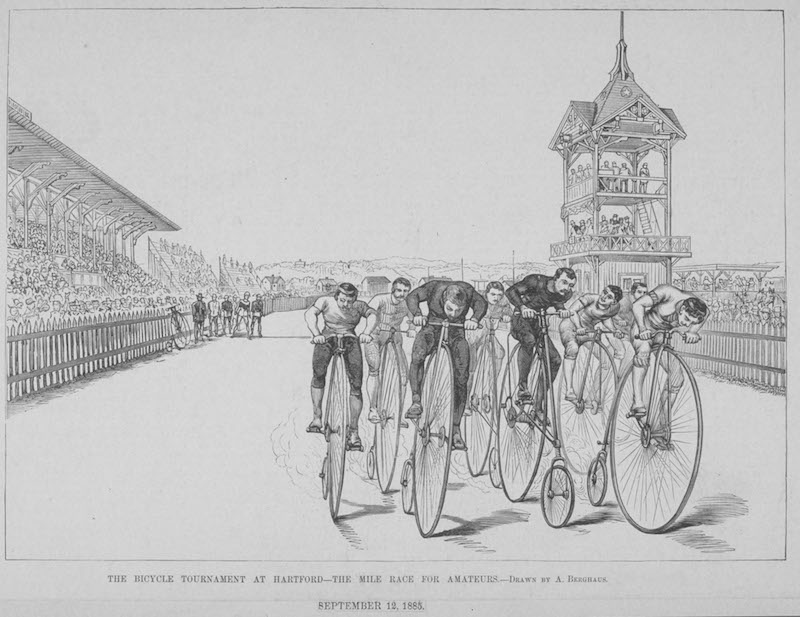

This drawing, originally published in Harper’s Weekly (1885) by illustrator Albert Berghaus, shows the final heat of the one-mile open amateur bicycle race at Charter Oak Park in 1885. Note the crowds of spectators in the covered grandstands and the tall viewing platform to the right. The Connecticut Bicycle Club sponsored this series of races over a two-day tournament. At least 7,000 spectators attended. Source: The Connecticut Historical Society.

In September 1884, the Connecticut Bicycle Club mounted a race with prizes of $1,000. Hundreds of people lined the streets for a parade of over 100 bikers. They scheduled 12 races with riders from Hartford, Springfield and Boston. The top racer had a time of 3 minutes 3 seconds. Five thousand people came to the races in the first large-scale bike race West Hartford had seen. Colonel Pope was one of the officials of the races. The Courant reported:

Never before in this country has a more successful one day’s tournament been held, and never before in any race in the world has such good time been made as in the mile race… A comparison between such racing and horse racing must necessarily be to the advantage of the former sport, for there was no grumbling on the result of the contest and no boisterous language, and the auditors knew that the struggles they viewed between the race were honest and that the best man always won.

By the early 1890s, Pope developed a bicycle trust, which controlled all bicycle patents in the United States. For all bikes manufactured in the US he got $10 per bike. Pope changed the size of the front wheel to be equal in size to the back and had the rider sit between the wheels. This made the bicycles even easier to ride and democratized the athletic pursuit. The bicycle craze blossomed with this new invention in the 1890s. According to Ellsworth Grant in his article “The Miracle on Capital Avenue,” in the Hog River Journal in 2002, Weed employed 600 men making these “safety” bicycles. In the mid 1890s, Pope lorded over 18 acres of factory space on Capitol Avenue. He employed almost 4,000 people and produced 50,000 bicycles a year.

According to Pope, the main problem for bicyclists was that there were not safe, macadamized roads to ride. In 1880, he was one of the founders of the “League of American Wheelmen” to lobby local governments for improved roads. The late nineteenth century bicyclists long before the invention of the automobile spurred the “Good Roads Movement.” By the 1890s, much of West Hartford’s town budget was in building hard top roads.

Today, bicyclists are back at it, trying to improve the roads for riding. The context has changed dramatically as the gas-powered automobile is the main impetus for improved roads. But bicyclists want car drivers to share the road and allow them to feel safe as physicians once again encourage their patients to bike to keep fit.

James Talcott, Merchant and Philanthropist

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, April 2003

As the town plans for a new middle school on the east side of town, I wonder what we’ll call it. How have we named other schools? What does it say about the historical context and about the town’s values? School names can be an interesting source of information about both.

Talcott Junior High, on the corner of Quaker Lane and New Britain Avenue opened in 1922. Its opening was part of a reorganization of the town schools as they moved away from both the one room schoolhouse and the kindergarten to grade 8 school. James Talcott (1835-1916), lived in town for 19 years, and was “a successful merchant and member of a family long active in town and school affairs.” He moved to New York City at 19 to become a merchant and lived there until his death at the age of 81. His contact with the town seemed minimal after he left, but his career and public life in New York made him a man to emulate.

William Hurd Hillyer, James Talcott’s 1937 biographer, described him as a man who prospered on individual initiative, responsibility, morality, ethics, integrity, honesty, being honorable, kindly and steadfast and having a spirit of cooperation. He tied these values to Talcott’s Puritan work ethic. These values are part of the civic education public schools try to teach.

Hillyer also claimed that Talcott’s “pure English lineage” was a cause of his success. James Talcott descended from a man who shared the same name and migrated to America with Thomas Hooker in 1632. John Talcott was one of the founders of Hartford with Thomas Hooker in 1636 and Talcott Street in Hartford is named after him. He served as a Court Magistrate, was a Deputy from 1637 to 1652, and was Treasurer of the colony from 1654 to his death in 1660. His son, John Talcott, Jr. succeeded his father as Treasurer of the colony. Another descendant, Joseph Talcott was Governor of Connecticut from 1725 to 1742.

Samuel Talcott of West Hartford built a mill near the pottery in 1828 where he and his sons carried on a thriving wool business for years. Talcott’s sheep provided wool for his woolen business. They had a fulling shop where the cloth was made ready for market and stored. The businesses were part of his 1000 acres of land which extended from New Britain Avenue as far as Flatbush Avenue, to the west side of Quaker Lane near where Trout Brook crosses the road.

Samuel Talcott’s son Seth took over the mill and he was the father to James. As a young man, James and his ox team had the task of bringing goods to market in Hartford. When his brother opened up a woolen knitting mill in New Britain, James got involved at the outset as a merchant. As a man of just 19, he set out for New York City in 1854, and set up shop. This was right when West Hartford became an independent town.

In the 1850s merchants were the pillars of capital and lived in the big cities. They were generally the wealthiest men and were civic leaders. As a merchant, James Talcott sold his brothers’ goods to stores like New York’s A.T. Stewart, the biggest retail merchant in the country, and Philadelphia’s Wanamakers, the country’s first department store. He was successful, according to Hillyer, because of his honesty and integrity, and because the knitted woolen goods from this brother’s factory in New Britain were so good.

Once established in New York City, James Talcott married Henrietta Francis in 1861. Her uncle had a farm in West Hartford. James probably met her on a Thanksgiving break where he spent a few days every year with his parents in West Hartford. James and Henrietta bought a house at 20 West 39th Street – a four-story brick house. He lived there for 12 years and his three sons J. Frederick, Arthur and Frank were born there. They later had two daughters.

Every Saturday afternoon, Mrs. Talcott drove in the family carriage downtown to bring Mr. Talcott home. She never drove to the front of his building on Franklin Street because both she and Mr. Talcott believed that it would have been “unnecessarily ostentatious” for him to step into a fine carriage with a coachman and footman in front of his business.

In 1876 they bought a five story brownstone for $90,000 cash at 7 West 57th Street. This was a new and fashionable part of the city which had become so because William H. Vanderbilt and other wealthy New Yorkers had built imposing homes there. But probably more important was the opening of Central Park where New Yorkers could skate, sleigh, ride, drive, and play outdoor games like archery, croquet, and lawn tennis. Talcott had enough money and social standing to be a part of this West Side life.

In this home, well staffed with servants, there was a routine. Mrs. Talcott served tea at five o’clock each day. Friends usually came by to visit at this time. Dinner was always served at 7:30 and Mr. Talcott always dressed “in full evening dress” for the occasion whether there were guests or not. He served no wine or liquor, but an imported sparkling mineral water.

Talcott showed a deep interest in religion and took an active part in church affairs. Talcott joined the Broadway Tabernacle Church (Congregational) and became a member of the Church Committee at age 30 when, traditionally, this group was made of the elders of the church. He found time for mission work in Bethany Parish at 34th and 10th, in one of the poorest sections of the city.

James Talcott was a Republican and he was mentioned as a candidate for Mayor of New York City in 1890, but never ran. He was a protectionist and one of the staunchest supporters of the American Protective Tariff League, a position that most merchants took. He spent time fighting Democratically controlled Tammany Hall.

As a philanthropist he gave away 10 percent of his wealth. He saw himself as a steward of his wealth. Some of his interests included a library built at the Northfield School, Massachusetts, a dormitory built at Oberlin College, the Grace Talcott Hospital at Shunteh-foo, China, planting an arboretum at Mt. Holyoke College, and endowing a professorship for religion at Barnard College. He was one of the founders of the Jerry McAuley Water Street Mission, the Cremorne Mission and the Home for Intemperate Men.

In 1897, Talcott gave books and money to help establish West Hartford’s free public library. Until then, the library was part of the First Congregational Church.

In his later years, Talcott devoted his life to peace. He went to Lake Mohonk, America’s peace center each fall. He supported peace in trade and in politics. Talcott was 80 when war broke out in Europe and he expressed his disapproval. He died peacefully in 1916 at Lake Mohonk, before the U.S. entered the war.

The 1920s, the post World War I era, was a time when “the business of America was business.” The town’s population grew to almost 9,000 by 1920, and middle class professionals started to move to West Hartford, the streetcar suburb. James Talcott’s career must have appealed to them because of his monetary success, his moral and ethical purity, and his charitable works. Many other members of the family were involved in West Hartford governmental affairs, but the town officials chose this self-made business leader and philanthropist, this champion of hard work, integrity, honesty and success, to be a role model for the town.

Elmwood Suburbs

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, June 2011. Thank you to Jeffrey Murray, Conard High School junior, whose research paper, “Elmwood: From Rural Community to Working Class Suburb,” won the 2011 Freeman and Mary Meyer Prize for Excellence in Local History.

In the early 20th century, the Elmwood section of West Hartford developed its suburban character on a parallel to West Hartford center’s development. The same ingredients nourished growth in both places: transportation in the form of the trolley, farmers ready to sell their land to developers, real estate developers, and people looking to move out of the city. It all added up to a growth in population and an eclectic mix of residential, industrial, commercial, religious and educational institutions. This mix of buildings and people gives Elmwood the separate identity it retains today.

In 1900, when the trolley company laid a track down New Britain Avenue ending at East Street (now Quaker Lane), suburban development picked up. Before the trolley, residents could jump on the steam train running through the southeast corner of town for $24 per year. But in 1899, the train raised the rates to $60 per year and passengers lobbied to bring the trolley to Elmwood. Within a year the line opened.

As people moved out of Hartford and New Britain and into West Hartford, government services expanded. In 1900 the town added onto the Elmwood School, built as a two-room schoolhouse in 1888.

In 1901, the West End Land Company bought land in Elmwood on the present site of Yale and Florence Streets. Their handbills to sell the properties advertised free trolley rides. Four years later, F.C. Rockwell, who developed the Boulevard in the Center between Main and Trout Brook, sold land on New Britain Avenue to developer Terry Chapin. This land was subdivided by 1909 into more than 60 lots.

Wallace B. Goodwin, grandson of Harvey Goodwin, the founder of Goodwin Pottery, a local industry since the early 1800s, began to develop Elmwood with small single-family homes. He wanted to sell lots to people of moderate means. Goodwin also wanted to retain the agricultural nature of the residential area. In an advertisement for “Bungalow Farms,” on Newington Road he wrote, “If you could own your own home with a real little farm, where you could raise your own vegetables and chickens and be in Hartford or New Britain within fifteen or twenty minutes’ ride, now wouldn’t that be ideal?” He sold “acre lots and bungalows” in a “beautiful restricted section.” He added that the lots were “close to Elmwood Trolley and Railroad Stations.” Goodwin appeared in the ad, holding a plot of land with a bungalow, set on a country road.

Wallace B. Goodwin, in the real estate and insurance business, was a direct descendant of the founder of Goodwin Pottery. In 1936 he bought land west of Ridgewood Road to create a development around Wood Pond and Woodridge Lake, once the ice business ended. Source: Display Ad 65, The Hartford Courant, May 24, 1914.

In 1913, Goodwin planned to develop an Elmwood that would be distinct from developments in the center of town. Mentioning New Britain in his ad and suggesting that residents could grow their own vegetables were attempts to market a suburban neighborhood with rural charm that differed from the developments in the center of town.

On April 25, 1915, the Hartford Courant reported that Goodwin bought land from F.W. Talcott on the east side of East Street for developing this “splendid tract” in a “restricted way.” Goodwin called the area “Burgoyne Gardens.” Houses built on this tract had a view of Talcott Mountain and Charter Oak Park, across Trout Brook from the development. Sewers and piped in water both served this neighborhood. Goodwin had room for about 40 homes on the plot and he planned to build both single and two-family homes.

Goodwin’s development was within walking distance of a post office, library, and school with easy access to the trolley and train, which could whisk commuters into Hartford. The post office built in 1873, was a sign that Elmwood had a separate identity from West Hartford, which became independent from Hartford in 1854, just 19 years earlier. Also in 1873 the Elmwood Community Church set up a Sunday school, which met at the Elmwood School. In 1876, this group of Congregationalists built the Elmwood Chapel at New Britain Avenue and Grove Street. In 1926 this church moved to its present location on Newington Road. By the mid 1920s, the population of Elmwood stood at about 2,000.

Meanwhile, Wallace B. Goodwin continued to expand his reach from real estate developer to purveyor of insurance on furniture and buildings, mortgages, and selling ready-built sheds to be used as garages.

In 1917, the Catholic Transcript reported that the Elmwood church, St. Brigid, was the first Catholic Church to be erected in West Hartford. According to the Transcript, “The Town is fast growing and the new church, which is at the southern end, promises one day to be a considerable Catholic center.” The Church started as a mission of St. Lawrence O’Toole Church, in Hartford just about a mile east of Cambridge Street and New Britain Avenue.

Elmwood continued to develop its own identity as a working class suburb with manufacturing and farms, and an active political life. The area residents saw themselves as outsiders from those who lived in the town center. In an attempt to get fire protection in Elmwood in 1919, the “Men’s Union” “turned out in full battalion strength” to a special fire district meeting at the Town Hall in the center of town. They hired cars to take them to the town hall and surprised the “unsuspecting townsmen of the north end.” Those running the meeting were met by “a storm of protest.”

The Elmwood men got their way when the Fire District voted to give fire hydrants to Elmwood by increasing the mill rate by one mill. The Men’s Union’s next step was to establish their own fire station in town which finally came to fruition in 1919. It was clear that the increased fire protection would add to the value of houses in Elmwood.

In 1922, Talcott Junior High opened on land contributed by the Talcott Estate. Talcott and Plant Junior Highs were among the first junior high schools built in Connecticut. Six years later in 1928, as the population in Elmwood grew, the town tore down the Elmwood School and replaced it with the Elmwood Grammar School fashioned after the Beach Park School on Steele Road and the Morley School on Fern Street.

The Hartford Courant claimed that this subdivision was “an excellent location for the suburban dweller.” By 1925, those who moved to Elmwood made a choice to live in a community proud of their factories and railroad tracks as well as the churches, schools, library and post office which helped to develop an identity that makes a uniquely Elmwood section of town.

The Prospect Casino

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, May 2009

An article in the Hartford Courant from February 25, 1901, “Casino to Close: Clubhouse on Farmington Avenue to be Leased or Sold,” caught my eye recently. The subtitle read “It has not been much patronized of late, Golf and the Country Club at Farmington Avenue proving stronger attractions—Pleasant Building, but Little Used this Winter.”

I had known the casino was on the southwest corner of Farmington Avenue and Prospect near where St. John’s Episcopal Church stands today. It struck me as not quite right that a “dry town” would have a casino, but I had never seen much more than a mention of the place in town.

The term casino did not always refer to a place for gambling and West Hartford’s casino was far from our present definition of a casino. Originally the term referred to a small Italian villa, summerhouse or pavilion built for pleasure, usually on the grounds of a larger Italian villa. Its meaning changed through the 19th century, but this original meaning seemed a better fit for the “casino” built in West Hartford in 1894.

On January 30, 1894, residents of the West End of Hartford and the east end of West Hartford met at Whiting Lane Schoolhouse to organize building “a clubhouse and casino” to act as a social club on Farmington Avenue. It was named: “The Neighborhood Club Company.” A group of 20 men paid subscriptions worth $5,000 on the way to the needed amount of $7,000. The purpose of the meeting was to talk about building the hall to be “suitable for such amusements as are desired.” H.C. Judd, F.G. Whitmore, Anson Brainerd, and John O. Enders were four of the founders.

The club chose among a dozen architectural plans. An 1894 Courant article described it:

a low pitched roof rises at the front to a height sufficient for two floors and is surmounted by a platform where a flag staff rises to a height of fifty feet from the ground. From the roof projects a pleasing dormer balcony. The style of architecture is semi-colonial.

Inside, the clubhouse had a reception hall, an office, a ladies’ parlor, reading room, billiard room, assembly hall (66 x 44 feet) with a capacity for seating 500 people for dinner. They built a stage in this room as well. On the second floor, there was an office for the secretary, and a lounging and smoking room. In the basement they built two bowling alleys, a kitchen, dressing rooms, and baths. The building was heated by hot water, and lit, “for the present,” by gas. A wide veranda surrounded the clubhouse on two sides. In the backyard, they planned to build three tennis courts.

By time the building was finished, its costs had more than tripled to $23,000. Of the 140 stockholders, about 60 percent of the members lived in West Hartford along Farmington Avenue and Prospect. The other 40 percent lived in the city. According to the rules of the club, “it is intended that the tone of the club life shall be at all times elevating and that nothing in the nature of gaming or carousal shall ever be allowed.” They planned for “ladies and young people” to be part of the club. Clearly built before the term casino evolved, the rules were clear: betting and gambling were prohibited by the by-laws as was selling or keeping liquor.

Members held lectures, listened to musicians, hosted theatrical performances, had fairs, and hosted balls. Members went to the casino to read, play games, and just talk. They allowed the Farmington Avenue Christian Association to hold services there until they found a permanent home.

The opening party for the club in February 1895 was a real gala! The members decorated the building in “Oriental Luxuriance” and “well-known society people (who) danced the hours away.” A Courant reporter wrote:

Society was out in full force and the company was brilliant in the costumes of the ladies, handsome gowns, beautiful bouquets and other accessories of charming toilets. There was a large number of well known people present, and while the chief attraction was the dancing in the ballroom there was a good deal of social chat in the spacious parlors and in the brilliant rooms.

Over time the members changed their club’s name from the Neighborhood to the Casino Club. The building was used often for theatrical performances, dances and receptions. When it was warm, the managers enclosed the verandah in cloth in the evening. Women and children came to the club frequently and it kept its reputation as a family club.

However, in 1896, the Hartford Golf Club opened. In the late 1890s, the Farmington Golf Club on Outlook Avenue opened. The Fern Street Golf Club was also a going concern at the same time. According to the Courant, interest in the Casino Club fell off when the golf clubs opened.

In February 1901, the members decided to close the Casino and they sold the building at a loss for $15,000 to Dr. Naylor. He planned to convert the casino into a home, but never moved in. He leased the building for various functions including entertainment, and Miss B.A. Hollister’s ladies’ gymnastic class.

On December 18, 1902 a spectacular fire burned the casino to the ground. The fire began in the rear of the building at about 9:30 at night. Neighbors made the call to the Hartford Fire Department and several companies arrived, but they were not allowed to start fighting the fire until Chief Eaton, who was two and a third miles away, arrived and gave special orders to fight the fire across the city line.

The fire companies took more than two hours to put the fire out. Hartford residents complained about having to pay their tax money for fire protection for West Hartford. In fact, many people moved to West Hartford because the tax rate was lower. However, Hartford seemed to supply both police and fire protection to the growing suburb of just over 3,000 residents. There had been talk of a new West Hartford fire district, but the West Hartford selectmen did not vote to fund one until 1909 and the fire company was finally completed in 1915, not far from the site of the fire.

As this new upper middle class moved to West Hartford, they organized, developed, and built new ways to spend their leisure time. The Prospect Casino had a short life, but it was an important symbol of the change in West Hartford from farm town to suburb. Those who worked in Hartford’s white-collar jobs organized and joined private clubs for their recreation. These clubs, as well as their new residences in the suburbs, helped define this new middle class.

Charter Oak School

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, May 2013

In March 2013, West Hartford’s Board of Education voted to build the first new elementary school since Norfeldt School was built in 1964. A new Charter Oak School, with a price tag of $40 million (with the town paying about $8 million), will open in 2016. The present school houses 270 students and the new school will have room for 560 students from the neighborhood and magnet students from all over town. Charter Oak’s scope and size has changed many times in its history. This investment in a state of the art building will help to do what Board of Education Chair Madeleine McKernan dreamed of over 40 years ago: to provide an equal opportunity for all students no matter where they live in West Hartford.

In 1884, the Common School district of West Hartford built the original elementary school in the neighborhood. The one room schoolhouse on the south side of Flatbush Avenue (near the present day Home Depot) at first housed all eight grades, but as the population grew, three more rooms were added, and only K-4 students could fit in Charter Oak. Older students went to Smith School, or the Elmwood School on New Britain Avenue. This little four room Charter Oak area school had a capacity of 100 students. The current Charter Oak School was built in 1930 to accommodate kindergarten to grade 6.

The architect, Russell Barker planned for a 15-room building for 560 students with a price tag of $290,000. Superintendent Lloyd Bugbee planned this school as one of the first “modern” schools in the “American perpendicular” style with silver and black colors on the front of the building. One innovation in the building was the inlaid linoleum floor in the kindergarten room with inlaid children’s stories. Architects planned a library in the middle of the school.

Miss Bernice Patterson took on the role of teaching principal of the 4-room schoolhouse in 1924. In 1930, when the new school opened, she became the first principal. She served as principal for 22 years when Miss Harriet Foley replaced her.

A 2 ½ inch piece of the trunk section of the famous Charter Oak tree was displayed in the main corridor. Walter Korder, a local artist, received New Deal money in the 1930s to paint several fairy tale paintings that still hang in the building.

In 1941, the town took the playground behind the school to make fields. The school then acquired play space in the front of the school on Oakwood Avenue. In 1954, the School Board, built a cafeteria in the remodeled basement, after parents advocated for it so children would not need to walk home for lunch. Charter Oak students ate a hot lunch just like those who attended the new schools like Webster Hill (1949), Bugbee (1952), Duffy (1954), and Whiting Lane (1954).

In 1957, Building and Grounds added a fence around the entire play area. In 1958 a gym was added, again to keep up with the new schools being built. In 1963, enrollment declined as eminent domain forced families out of homes along the I-84 corridor. Charter Oak lost 60 students in that one year.

In September 1972, school administrators hoped to build a new large elementary school for 1,000 students for $4 million to replace Smith and Charter Oak. In 1972, the Hartford Courant reported that the Board of Education wanted “to replace the aging Smith, Charter Oak and Elmwood Schools.” The Board scaled down its plans to a 700 student school to replace just Smith and Charter Oak. But a lack of parental support led the Board to drop the proposal.

According to Board Chair Madeline McKernan, the main impetus for the new school was to provide an equal education to students in all areas of town. The Board felt that Charter Oak and Smith’s buildings did not provide an equal education for students in the poorest areas of town.

Instead, in November, the Board decided to renovate the existing Charter Oak and expand it so that Smith School could be closed. Parents at Smith promptly organized a group called Save our Schools (SOS) to make sure that Smith did not get shut down. The Board of Education backed off and allowed both schools to remain open and in 1974 voted for funds to rehab each school. In 1975, the Board of Education decided to close the Elmwood School due to declining enrollment. In the early 1980s, Smith closed as well.

Since the early 1990s, West Hartford’s Board of Education has been under pressure to racially integrate its elementary schools. The 1968 Racial Balance Act requires towns to integrate within their district by making sure that no school has a racial balance that is 25% above or below the town’s percentage for students of color. The 1994-5 K-2, 3-5 plan attempted to ameliorate this racial imbalance, but public outcry led to the Board of Education rescinding the program which led to three magnet elementary schools instead, hoping for voluntary integration. Charter Oak became one of those magnets.

In March 2013, a 20-member committee decided to build a new Charter Oak School rather than revamp the old. New diversity school legislation, designed by Senator Beth Bye and Representative Andrew Fleischmann, passed in 2012, allows for the town to receive up to 80 percent construction cost for reimbursement if the school is being built with a plan to reach racial balance goals. Regular construction reimbursement for West Hartford is 40%.

The story of Charter Oak School, a school named after a rebellious Connecticut event to protect democracy in the 1600s, represents much about our town. It was the third elementary school, after Beach Park and Morley, to be built in town. Its original architectural plan broke new ground and its changing demographics point to the change in West Hartford’s population in the past 40 years. Though the housing stock in its neighborhood has changed little, the skin color and languages of those who live in these houses has changed. The parents’ desire for a state of the art school to provide the best environment for their children, on the drawing board for the second time in 40 years, will soon become a reality.

West Hartford in 1896

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, January 2009. Thanks to Dick Kreitner for the atlas.

This fall a friend passed along a real treasure to me in my role as the Town Historian: a 112-year-old atlas of Hartford and West Hartford. The atlas provides unique information. It opens up a world to me that newspaper articles and even photographs cannot engender. The Atlas of the City of Hartford Connecticut, including also the Town of West Hartford tells me much about the economic world of West Hartford over a century ago. It defines the town of West Hartford as a town that supported agriculture and industry, as it became a suburb of Hartford, on which it depended for its economic well-being.

In 1896, West Hartford had about 2,500 residents and was just starting to move from farm town to suburb. L.J. Richards & Co. of Springfield, Massachusetts published the atlas based on records from Hartford and West Hartford municipal engineers and some of the publisher’s own engineers. There are 30 Plates in the book, 26 from Hartford, and four from West Hartford. You can browse through this atlas in the Local History Room in West Hartford’s Noah Webster Public Library, or their historical maps online page.

Plate 27 is a map of the entire town, showing every dwelling in town. The mapmakers delineated whether buildings were brick, wood, brick and wood, stone, iron, whether it was a barn stable or shed, or a greenhouse. The atlas includes the owners’ names for each dwelling and piece of land.

The map marks sewers under Park Street from Prospect past South Main, and on Fern, Quaker Lane, and the south end of Steele Road, a sure sign of the infrastructure built for residential neighborhoods. The street railway that traversed Farmington Avenue spanned the town from east to west. The Hartford and West Hartford Horse Railroad Company, incorporated in 1863 sent the line out to West Hartford in 1889.

Wallace Thomson founded the W.W. Thomson Company at 146 South Main Street in 1899. Originally they grew vegetables and produce that they sold to farmer’s markets in the region. His son, W. Pomeroy Thomson, produced over 30 new varieties of carnations between 1958 and 1988 in West Hartford, Florida, and Bogota, Colombia. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

By the 1890s, West Hartford’s farmers specialized in dairy. The two creameries in town, Highland Creamery on the southwest corner of Albany Avenue and Mountain Road and the Elmwood Creamery owned by C.M. Beach, now part of Beachland Park, were important parts of this agricultural base. According to William H. Hall in his West Hartford (1930), the creamery was supplied by the farms that surrounded each dairy.

On Plate 27, the publishers named two farms in town: Boswell Farm on the west side of South Main where Rockledge is today, and Maplewood owned by F.A. Thomson across the street. These farms were just to the north of the Vine Hill Farm and Grist Mill which included land on three corners of New Britain Avenue and South Main Street.

Gristmills in town at the time are a reflection of the continued agricultural base. There were the Trout Brook Grist Mill on North Main where Trout Brook crosses near American School for the Deaf, and the grist mill next to the Elmwood Creamery in today’s Beachland Park. Daniels Mill Company owned a gristmill on the corner of Simsbury Road and Bloomfield Avenue. Daniels Mill Co. was established in 1835, according to the directory at the back of the atlas. Here, the publishers listed “well-known citizens, representing the business, professional and educational interest of the city, through whose hearty support alone the completion of this volume has been made possible.” Daniels Mill sold wholesale and retail flour, feed, grain, hay and straw. “Grain by the carload” was their specialty. Their headquarters at 40 Elm Street in Hartford represented the close connection between the economies of Hartford and West Hartford.

Farmers specialized in greenhouse grown plants as well. There were greenhouses on Whiting Lane owned by Alfred Whiting. Next to the Hartford Brick Company on New Park Avenue stood the greenhouses of Charles K. Swenson, one of the many Swedish immigrants who worked with plants. W.E. Wallace sold nursery goods on the corner of Farmington Avenue and Quaker Lane from his greenhouse. According to Hall’s book, Wales Andrews had four greenhouses on the corner of New Britain Avenue and Grove Street where he specialized in growing cucumbers.

Many successful businessmen who worked in Hartford, lived in West Hartford and supported the making of the Atlas are listed in the directory in the back of the book. Charles M. Beach of the Beach Dye Works, J.J. Enders of State Savings Bank, J.L. English, secretary of Aetna Life who lived on Fern Street, and Bernard Caya, contractor lived on Prospect Avenue. F.C. Rockwell, who was the head of the Bonsilate Box Co. lived on Prospect Avenue. He subdivided the land along the Boulevard as he looked forward to one of the first suburban developments in town.

E.H. Arnold & Sons used the pond from the dammed up Trout Brook at Farmington Avenue to harvest ice. His Trout Brook Ice and Feed Company needed five buildings to take care of its business. Headquarters for Arnold’s building were on Asylum Avenue downtown. His company was both wholesale and retail selling ice and grain.

By 1896, West Hartford also had its share of industry. The clay soil led to brick making as a lucrative business. There were three brick companies in town. On New Park Avenue, with railroad spurs right into their yards were the Hartford Brick Company and across the tracks, the Charter Oak Brick Company. On the corner of Prospect and Caya Avenue was the Dennis & Co. Brick Manufacturers.

Brickmakers used the clay soil in the southeast section of town to build several lucrative businesses. The Phoenix Brick Company, Park Brick Company, and the brickyards of Michael Kane lined the railroad line in the industrial section of town. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

Along the railroad tracks in the southeast section of town industry grew. The Whitlock Coil and Pipe Company was across the tracks from the Goodwin Brothers Pottery. Whitlock Coil and Pipe opened its doors in 1892 and manufactured coiled pipe for use with steam boilers. The Goodwin Brothers began the pottery business to take advantage of the clay, just as the brickmakers did. They sold their jugs and jars across the continent.

For entertainment, on the corner of Prospect and Farmington where St. John’s Episcopal Church stands today, was the Prospect Casino. On Prospect and New Park, race enthusiasts could go to the Charter Oak Driving Park. There was a bandstand, a grandstand, and a half-mile track. Both of these establishments depended on Hartford residents for their success.

The center was beginning to be a retail center. Where the present day library sits was Burr’s Carriage Repository and Hardware Store. Buckland’s Store and Post Office stood at the corner of Main and Farmington. But, these are the only two retail establishments in the center. The real growth came in the 1930s.

Economically, West Hartford continued to depend on Hartford. Farmers sold their produce to Hartford residents, the railroad that passed through the southeast corner of town connected goods to the city center, and Hartford businessmen brought value as they began to settle in the residential suburb. L.J. Richards’ Atlas confirms that West Hartford’s prosperity depended on Hartford’s economy. In 1896, residents and businesses knew that their prosperity depended on the city. Today, many West Hartford residents continue to understand how West Hartford’s economy is tied to that of Hartford and the region that surrounds it.

A Day in This Town’s History: August 10, 1899

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, July 2009

An August 10, 1899 news brief from the Hartford Courant opens a window into West Hartford at the turn of the 20th century. This seven-paragraph article has 272 words and provides a sense of the fabric of a town changing from a farm town into a suburb.

Item one: Mrs. F.H. Stadtmuller as a ’Ceres" presided at the meeting of the Grange Tuesday evening. The hall was prettily decorated with stalks of corn and golden rod. Papers upon grains were read by Mrs. S.P. Griswold, D.G. Francis, Dr. Ganunack, Mrs. P.R. Day and Mrs. Paullson. It has been decided to postpone the matter of an excursion for the present.

Imagine Mrs. Stadtmuller dressed like the Roman goddess of agriculture, wearing a garland of ears of corn. Ceres was an elected position in the Grange, which started as a secret organization in town in 1887 with 32 charter members. The purpose of the Grange was to improve social connections and fight the economic backwardness of farmers.

The interests of West Hartford Grange 58 included education, improvement in public highways, rural mail delivery and town affairs. Yearly, they prepared exhibits for the annual state fairs at Charter Oak Park. According to Hall’s West Hartford, even in 1930, the Grange continued “its organization and its interest in the town.”

Stadtmuller presided over the meeting, introducing the five speakers, three of whom were women. In 1900, as this town’s population topped 3,000, some suburban developments like Buena Vista and West Hartford Heights were beginning as the trolley made transportation to Hartford easier.

While “grains” were being celebrated, however, the production of grain acreage in New England dwindled. Between 1880 and 1930, almost 19 million acres in New England were taken out of farming, and the number of farms declined by 31 percent.

The surviving farms in town specialized in dairy and market gardens providing plantings for suburban homes. Mrs. Stadtmuller was the wife of Frank E. Stadtmuller, who from 1885 to 1907 managed the Beach’s Vine Hill Farm, which occupied acreage from New Britain Avenue to South Main Street to South Quaker Lane. This dairy farm was a model for the state in producing “baby’s milk.” While Vine Hill continued to prosper for another two decades, farmland was becoming more valuable for residential housing than for farming. Perhaps the Grange was glorifying an agricultural life that they saw slipping away.

Item two: The Rev. John Freeborg held a meeting for the Swedish people at the Baptist Church. A considerable number of Swedes are employed in town and they are interested to hear preaching in their own language and attend the meetings as well.

By 1900, Swedes were one of the largest immigrant groups in town. Between 1851 and 1930 as much as 25 percent of the Swedish population emigrated to the United States. A second wave of immigration in the 1880s and 1890s found young Swedes settling in Connecticut near urban areas.

In 1970, this town had the highest percentage of people of Swedish background in the state. Swedes settled in the Park Road area, building two- and three-family houses and starting businesses.

At one time, the building owned by Bazilians was a Swedish grocery story. Still remaining on Park Road are Hall’s Market, where you can still buy Swedish sausage called korv, and A.C. Petersen’s.

According to Butterworth, Grant and Woodworth in Celebrate! West Hartford (2003), 20 Swedish immigrants from West Hartford, New Britain and Hartford formed a Methodist church in 1895. They built their first church on the corner of Lockwood Terrace and the Boulevard in 1921. Today that church is the Boulevard Baptist Church. The Swedish Methodist Church finally moved to Berkshire Road and New Britain Avenue and today is known as the West Hartford United Methodist Church.

The ability of a Swede who was probably a Methodist to speak at a Baptist Church speaks to the interdenominational sharing in our town. The town’s many denominations have shared pulpits in times of disaster and overcrowding.

Item three: Millie Fulton, youngest daughter of C.W. Fulton, received a bad cut just below the knee from a piece of glass while playing about the mill pond the other day. Dr. Alcott, who was called, was obliged to sew up the wound.

The mill pond on Trout Brook was on the north side of Farmington Avenue. This pond was used in the winters to harvest ice, but in the summer must have been a great place, except for the glass, to go for a swim.

Dr. Ralph W.E. Alcott was one of the doctors in town at the turn of the century. In the birth records, his name appears as attending to the delivery of babies in people’s homes before the advent of having babies in hospitals. He was involved in promoting the development of a sewer system here at the turn of the century as an important development to protect against the spread of disease.

Item four: Misses Helen and Elizabeth Hubbard are at Branford for a week. Mrs. E.M. Peck is visiting relatives in West Haven. A daughter was born recently to Mr. and Mrs. John Hoye.

These three tidbits of information reflect on the small town that this was in 1899. Vacations and visits were noted weekly. A trip to Branford was not so difficult for residents because of the train lines that ran to the shore. By the 1880s, with the rise of factories, taking a week-long vacation became popular. Many residents owned or rented cottages on the Connecticut shore.

Item five: A resident of Charter Oak was before Justice A.C. Sternberg last night charged with stealing corn from the garden of Mrs. E.A. Talcott near East Street, Elmwood. The accused was found in the corn after dark by Herbert Talcott, but claimed that he was there for other purposes and was an honest man. Bags found on the ground he disclaimed owning. The accused was supported in his testimony by Mrs. Teresa Buck of Charter Oak. As the theft was not proved, the case was nolled. There has been considerable complaint of the theft of garden truck from the region bordering on Charter Oak.

In the alleged burglary in the 1899 paper, a frustrated farmer, Mrs. E.A. Talcott, tried to find who was stealing her corn. A character witness, vouching for the innocence of the accused, helped to get the case nolled. There was no lack of tension in turn of the century West Hartford.

Judge Adolph C. Sternberg served in the state legislature from 1895-96. He was a German immigrant and the son of a highly educated man who moved here in 1854. He grew up with seven brothers and one sister on the southern end of Mountain Road where it meets Sedgwick Road.

Sternberg, as well as being a judge, helped move this town from the town meeting to the town council manager system of government. In 1916, there was so much controversy over the valuation of agricultural and residential land between farmers and suburbanites that residents rejected the assessment list and the town could collect no taxes for that year, having to borrow to pay its expenses. This controversy moved the town to adopt a new town charter in 1919 that made it the first town in the state to adopt this progressive form of government.

This news from the summer of 1899 describes a farm town with community organizations, immigrants, people wealthy enough to go on week-long vacations and law breaking. The Hartford Courant kept people apprised of not only the political and organizational news, but also of the social fabric of the town that helped to stitch us into a community.

Abraham Janes, Blacksmith

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, February 2012

My article this month started by researching what was happening in Town 100 years ago. That search took me to the Historical Hartford Courant, just a click away through the West Hartford Public Library online service. There, I found that a January 14, 1912 fire raged for five hours at Abraham Janes’ Blacksmith and Carriage Shop, 921 Farmington Avenue. The fire displaced two families, and destroyed over $12,000 worth of property. Janes would later rebuild his carriage and blacksmith shop and run it well into the 1920s.

That sounded like a story to me: perseverance and grit with community support. So, I’d write about the fire and how the Janes business was rebuilt. Initially, I found two articles on the fire and thought I was set.

At the time of the fire, Mr. Janes, his wife, their six children and an apprentice lived over the repository of his blacksmith shop. Walter Payne, an employee of the Hartford Water Board and his wife and three children lived over the blacksmith shop. The first floor of the building was a paint shop, blacksmith shop, the repository and an office. The basement had two forges, wood working machinery and storage booths.

When the fire broke out, Mr. Janes and two others rescued the eight sleeping children just before they were consumed by fire. West Hartford’s volunteer Fountain Hose Company rushed to put out the fire. The nearby Congregational Church’s bell called the volunteer firemen who rushed to the scene. The row of houses on Nichols Court that ran parallel to Raymond Road, (then School Street), did not catch fire because the night was so still. Reports claimed the temperature was 16 below zero.

Janes had insured the property for $11,000. The loss was close to $12,000. The Payne family was only able to save a small trunk of clothing and a few bedclothes. Several wagons and sleighs and three cars were saved, but another car burned. A month later, the insurance company had still not paid Janes. This stopped Janes’ attempts to build a temporary shed to continue jobbing and horseshoeing. Janes, according to the Courant, had not been idle, attending to his customers at their homes or elsewhere as soon as he got the materials needed to shoe. His plans were to rebuild a one-story shop on the foundation of the burned building. Still, he took a loss and had to borrow money to keep his son in college.

Part of the story about fires is not just about how the victims reacted, but how the community kicked in. According to the Courant, the response was “generous.” The women of the First Church met in the parlor the next Monday morning to work on articles of clothing for the Janes children. The pastor of the Paynes South Park Methodist Church asked for help for their 6, 4, and 2 year old children. Congregants donated $75 to the Paynes.

But who was this man, Janes? Like most life stories, his was complicated. There were articles about him running afoul of the law – passing a standing trolley, trying to collect money from customers who stiffed him, and in 1931, having his house on Quaker Lane go into foreclosure.

A continued search led me to more features on Janes. As cars became the mode of transportation, and as the role of a blacksmith changed from shoeing horses to specialty work, the Courant memorialized him in one article “Childhood Trade Brings Him Fame: Abraham Janes of West Hartford Follows Art of Smithy His Father Taught Him As A Boy in Newfoundland,” (1927) and a year later, “Abraham Janes, Artist in Wrought Iron Work: Sparks Fly From the Anvil Where, Under an Expert’s Hands, Modern Iron Becomes Latches, Grills, and Lanterns in the Style of Other Days” (1928).

In these articles I found out that Abraham Janes was born in 1872 in Brigus, Newfoundland, and grew up there where he apprenticed to his blacksmith father for 10 years. At age 17 Janes went to the Arctic on Peary’s first polar expedition. He set up a forge on Turnavik Island, mending the dog sleds and iron needed for exploration over the northern ice and for the ship. In 1898, at age 26, he emigrated to Hartford and opened his shop on Farmington Avenue. For the 27 years of his traditional blacksmith shop, he claimed, he made 53 vehicles per year and shoed hundreds of horses. One day he shod a pair of horses in 34 minutes without assistance. On another day, in 18 hours, he shod 53 horses. When there was a strike and riot in Ansonia in 1901, the cavalry was called out to stop the strike. Janes and an assistant went to the stables and, working under pressure, shod 43 horses between 2 A.M and 7 A.M.

Janes got involved in the community as well. After the shop burned, he moved to Quaker Lane between Farmington and Park. In 1912, he joined on with Theodore Roosevelt’s Bull Moose Party, attending a local convention. In 1913 he was elected gatekeeper of the Grange. He served as a member of the Fountain Hose Company No. 1 apparatus committee, being part of rebuilding the combination truck to equip it for fire fighting. He was the head of the committee to build a new firehouse shed a few years after the fire burned his place of work.

And, the Courant reported, that Janes’ work changed with the times. By the late 1920s, Janes, at age 56, still worked at the shop, but made thumb latches, butterfly hinges, grills, and balcony railings for bars and clubs as far away as New York and New Jersey. Janes fashioned all the hand-wrought iron at the Hartford Theological Seminary (now the University of Connecticut Law School), the window grills on the Fire Department in Hartford, the balconies and stair rail at the Fuller Brush building, the Spanish Balconies at the Hartford Club dining rooms, and iron work on West Hartford homes on Sycamore, Albany Avenue, and Whiting Lane.

As I searched for Janes’ obituary, to round out his story, it was not in the Courant. One of his 10 siblings died in 1940 and Abraham Janes was listed as living in Memphis, Tennessee. His wife, Lillian Janes died in 1957 at age 84, while living on Lancaster Road and her obituary claimed she died a widow. She left four sons and three daughters, three of whom lived in West Hartford.

Janes’ story was more of a puzzle than I thought. Where he was between 1931 and 1957 is not clear. In a Google search I found a family genealogy website produced by one of his 37 grandchildren. Several comments under his photograph helped to put flesh on his bones. One grandchild said:

Grandpa Janes (Abraham) was a good looking man, my Dad once said he didn’t smoke, drink or swear and had only one weakness: women. My Dad was attending Norwich University when the separation occurred between our grandparents. He left school and went home to help support the family.

I’m left to speculate that Abraham left Lillian sometime during the Depression, perhaps as the house went into foreclosure. Perhaps his trips to New York City to sell his specialized wares opened up new horizons. Losing his house to foreclosure might have been too much for his pride to stay in West Hartford. Or maybe, like his grandson suggested, there was another woman that drew him away from his adopted town. I think there are some readers who may remember his shop on Farmington Avenue or knew his family. Can you help me fill in the story? Research that started with a fire 100 years ago led to a master craftsman who changed with the times but whose full story is still not complete.

Henry Selden: A Man Who Changed with the Times

Originally appeared in Hartford Life, December 2001. Thank you to Bob Strickland, a long time resident of Selden Hill, who wants to keep the memory of the Seldens alive, and lent me several articles.

The life of West Hartford resident Henry Hezekiah Selden (1854-1932), symbolizes the sweeping changes in the United States as the economy and technology modernized our nation. Historians have described how the Second Industrial Revolution in the post Civil War period revolutionized the lives of average Americans. How did a man like Selden adapt to these changes while he retained his life as a traditional dairy farmer?

In 1776, the Selden family moved to Great Hill in what was then Farmington. When Henry Selden was five, in 1859, West Hartford annexed about 330 acres known as Selden Hill and now known as Buena Vista, in response to a petition by Henry’s uncle, Hezekiah Selden. This section of land is bounded by the reservoir on the north, Farmington on the west, West Farms Mall on the south, and Cornerstone Pool and the skating rink on the east.

By the mid-1800s, most New England farms had become dairy farms. With the new Erie Canal and railroad transportation, the opening of fertile land in Ohio, and the move westward, it was no longer profitable to grow wheat here. In the 1850s, some farmers in West Hartford grazed sheep, but the Selden’s chose to keep cows.

Henry attended the West School, a one-room schoolhouse that still stands on Mountain Road and now houses the West Hartford Art League. In the early 1870s, he spent a semester or two at Williston Academy in central Massachusetts to complete his education. He returned to the farm at Selden Hill to work for his father.

Henry Selden ran his ice cream parlor in West Hartford Center between 1898 and 1902 where LaSalle Road intersects with Farmington Avenue. Source: Selden Family.

As a dairy farmer, Henry cut and delivered hay in the summer, cut ice on Wood Pond in the winter, mended fences, and cared for livestock. The farm had 25 to 30 head of cattle, four horses and 150 acres of farmland. Their property had eight outbuildings and a 12-room farmhouse. A farmer who held 50 acres of land could live a good life.

Henry’s interest in new inventions started early. In the mid-1860s, when Henry was still a child, he watched men build the reservoir across Farmington Avenue from his parents’ dairy farm. Some of the workmen stayed at the Selden Farm while on the project. One of these workman’s jobs was to feed the horses and young Henry was fascinated by the small Seth Thomas alarm clock, which awakened him every morning. According to his granddaughter Dorothy Selden, the young worker was willing to trade the clock to Henry for some useless trinkets.

Henry’s fascination with things mechanical must have been piqued by the new pump organ at the First Congregational Church in the center of town. This church, the third building, was on the northwest corner of Farmington and Main and stood until 1957. Henry got a job in the church as the first boy to pump the new organ.

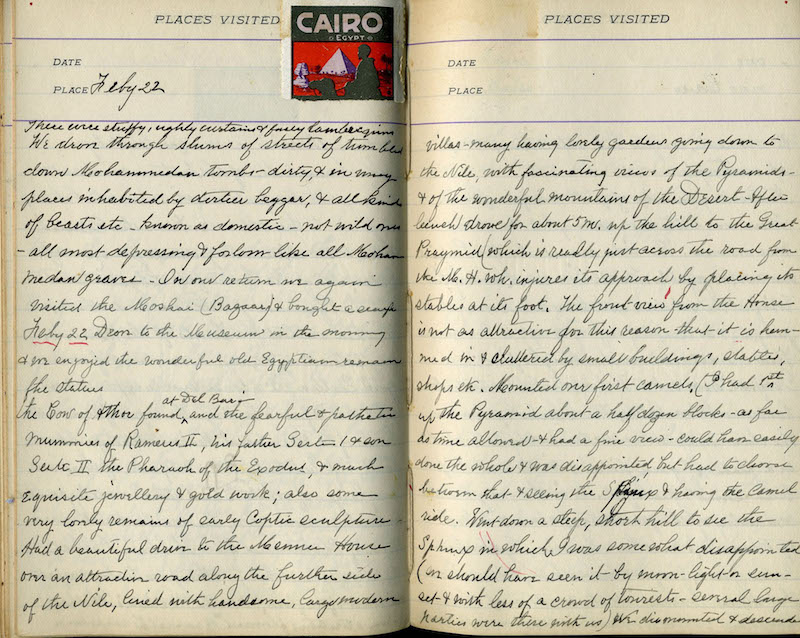

Henry’s interest in things technological continued into early adulthood. In 1876, when he was 22, he and his mother, father, aunt and uncle made the journey, by rail to Philadelphia, to celebrate the centennial of the United States. On August 21, the group of five set off for this city on the train from Hartford to New Haven. They boarded a boat in New Haven for New York City where they again boarded the train to Germantown Junction, Pennsylvania where they checked in at a hotel opposite the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. They stayed in Philadelphia for five days and Henry kept a diary of his visit. The exhibits from China, the Sandwich Islands, Belgium, and England intrigued him.

But he was most interested in Machinery Hall, the Saw Mill, the railroad exhibit and a printing shop. When his parents and aunt and uncle returned to the hotel, Henry stayed and rode the cars around the Centennial Exhibition. The next day they toured again, and Henry returned to Machinery Hall. He was so intrigued by the building, that in later years he named one of the buildings on his farm Machinery Hall. After a five-day visit, the Seldens took the 7:10 train out of Philadelphia, arrived in New York City at 10:30, hired a carriage, drove through the botanical gardens there, and arrived in Hartford by train by 9:30 p.m. The technology in Philadelphia intrigued the young farmer from West Hartford.

Henry, according to his granddaughter, preferred to work with machines rather than the soil. His interest in machines led him to build a mill on his property where he cut lumber for himself and his neighbors. He built a lathe powered by horses on a treadmill and he had his own repair shop and blacksmith shop.

Henry married Sarah Whiting in 1888 when he was an established bachelor at the age of 34. They went on to have eight children, and Henry taught them how to work on the farm. At the age of five, they started to do jobs on what was a prosperous farm. Most of Henry’s income came from milk, butter, and hay. There were times when he allowed his six and seven year olds to take his hay by themselves with their wagon to Hartford. His daughter, Rilla Selden (1898-1987) remembers wrapping pounds of butter in parchment and sitting high on the horse-drawn wagon with her father as he traveled his delivery route and getting down at each house to deliver the fresh butter at 25 cents per pound.

Henry was always looking for something new. Between 1898 and 1902, he and his sister-in-law opened the Selden Ice Cream Parlor in West Hartford Center at the present location of the Treva Restaurant. It was at the end of the trolley line that made it from Hartford to the center by 1889. According to Selden’s granddaughter Dorothy, the ice cream parlor was the first to use fresh fruit in their ice cream. The store closed when a nearby drug store began to serve ice cream.

Henry Selden bought his first car in 1918 when he was 64. He enjoyed riding in it, but decided not to drive it because he was so hard of hearing by that time that he couldn’t tell whether the motor was running. Once, when he did decide to drive it on the farm, he was heard yelling “Whoa! Whoa!” to stop it.

In 1926, 50 years after his trip to Philadelphia to celebrate the U.S. Centennial, Henry and two of his sons, Irving and Roland, took their Model T to Philadelphia for the U.S. Sesquicentennial. The fact that Henry enjoyed this celebration as much as he did as a young man is a testament to his willingness to use and learn about modern technology. He learned how to integrate it into the workings of his already established farm.

Elmwood’s Frank Stadtmuller

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, May 2006

Frank Stadtmuller came to public prominence as West Hartford was changing from a rural town to a suburb. He was a progressive farmer who advocated a role for farming in 20th century Connecticut and West Hartford.

As a Democrat in an overwhelmingly Republican town, Stadtmuller held positions as Justice of the Peace, a member of the school committee, head of the West Hartford Democratic Caucus, Town Selectman, Vestryman at St. John’s Episcopal Church, West Hartford’s Building Inspector, and West Hartford’s Health Officer. In the state, he served as the President of the Sheepbreeder’s Association, President of the Connecticut Dairymen’s Association, and the State Agricultural Commissioner. Stadtmuller always listed his place of residence as Elmwood.

Stadtmuller was born in 1861 on the Vine Hill Farm owned by Charles Mason Beach. His father Louis Stadtmuller was a German immigrant who worked for the Beaches. At age 6, the family moved to New Haven and Stadtmuller grew up there and graduated from Yale. He returned to Vine Hill in 1885 and, at age 24, took over the management of the farm for the next 30 years. He worked hand in hand with Beach’s son, Charles Edward who was one year younger than Stadtmuller.

Stadtmuller championed progressive farming. He and Charles Beach were the “inventors” of “baby’s milk” or what was known as “sanitary milk” in Connecticut. To produce baby’s milk, they kept the cows clean and the milkers free from disease. Each day, they tested the milk in the lab. Before the 1890s, infants only drank mother’s milk. Beach and Stadtmuller marketed cow’s milk to children.

Stadtmuller is most well known for being the originator of the certified milk business in Connecticut, between 1890 and 1920. His work force at Vine Hill farm is dressed in whites wearing caps and carrying covered buckets of milk. Their attempt to improve the sanitation milking cows led to advertising this milk for babies as “Clinical Nursery Milk.” Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

Stadtmuller was a businessman and an advocate as well as a farmer. He believed that milk had to be marketed and he believed the state had a role to play in doing this by inspecting milk, certifying its cleanliness, and providing price supports. In 1907, at a meeting of the Connecticut Dairymen’s Association, Stadtmuller gave a talk on problems with the low market price of milk.

However, having regulations and enforcement were two different things. At the state dairymen’s convention in 1913, the president of the group, Warren Davis, said that municipal milk inspection was “a joke.” He argued that the legislature would not appropriate enough money for inspection and that the inspection should be done by the State Health Department, rather than local health officers.

Stadtmuller believed that when each municipality inspected milk, the standards varied a great deal. The producer who lived closest to the point of distribution was inspected much more than the one further away and he believed that a state standard would help the situation. In 1917, as the State Dairy and Food Commissioner, he arrested the First Selectman of Southbury and four others for selling “watered milk.” These men felt the pressure of the cost of producing milk. Stadtmuller could use these men both as an example of the need for standards and the hard time that milk producers had producing a profit of any kind.

In 1914, in a speech before a meeting of the Men’s Union of the First Congregational Church, Stadtmuller decried the plight of the farmer in Connecticut, claiming that many of their problems were based on poor distribution of goods and the lack of cooperation between farmers. He also believed that the price of milk had to go up two cents per quart or even more men would give up dairy farming.

In that same year, as President of the Hartford County Rural Improvement Association, Stadtmuller encouraged those in attendance to value agriculture. Hartford County in 1909 produced $6 million worth of agricultural goods. He knew of large areas of “wasteland” that had gone to brush that could double Hartford County’s agricultural production. He urged “the children to stay on the farm instead of flocking to the city.” Cooperation among producers, he said, would lead to success.

Stadtmuller’s idea of an organization came to fruition in 1915 when his Hartford Country Rural Improvement Association (of which he was President) and the Board of Trade came together to discuss how they could help each other to save agriculture for the county. The amount of farmland decreased every decade, farmers moved west, and the many no longer thought of New England as an agricultural region. Stadtmuller seemed at his best when he used his position in various agencies to bring people together.

Stadtmuller also helped found and lead the West Hartford Business Men’s Association. In November 1910, they held a meeting on the subject of a public utilities commission. Stadtmuller’s Association called in two speakers from Hartford, Normand Allen and Ralph O. Wells, who explained the reasons that a commission was needed to control the “great public service corporations.” Allen, the owner of the Sage Allen Department Store explained that there “was no opposition to the great corporations.” He believed that there needed to be a way to secure the safety of employees on railways, to be sure that electric and gas meters measured use fairly, and that rates for electric and gas be controlled because they were unfair.

Allen proposed a public utilities commission of three to five men being paid $7,500 a piece to regulate the industry. The other speaker, Ralph O. Wells was concerned with the “baleful influence of the lobby in Connecticut legislation.” He believed that the Legislature was not controlled by reason but by corporations trading votes and “log rolling” to get what they needed. He believed that the electric and gas corporations had much too much power.

Stadtmuller believed that government regulation and associational cooperation could improve life for farmers and consumers. During the 1930s, with Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, the federal government, for the first time introduced price supports for agricultural products and established a “cost yardstick” for the cost of electrical power. In the 1910s, Elmwood’s Frank Stadtmuller (1861-1918) already brought these issues to the public’s eyes. Where many historians argue that the push for more government intervention in the economy came from the federal level, in fact the ideas were brewing on the local level right here in West Hartford a quarter of a century earlier, during the Progressive Era.

Historic Homes: Developing a Sense of Community

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, September 2005

In our fast-moving world, the permanence of our architecture inspires us to discover our sense of place. By observing houses in town, we can gain a better sense of our cultural roots, the history of the town and our human-made environment.

Homes are prized by the families who live in them; visiting them can provide us a direct connection to the past.

The Noah Webster House’s first historic house tour on September 17, 2005 will give us that chance. Five homes in the south end of town will be open to the public, three built in the colonial period, one in 1847 and one in 1900. Each provides a glimpse into the history of the town, the craftsmanship of architectural detail, and daily life in another time and place.

The first two houses on the tour are owned by the town: the Sarah Whitman Hooker House at 1237 New Britain Avenue, built in 1735, and the Noah Webster House and West Hartford Historical Society at 227 South Main Street, built in 1747.

The Sarah Whitman Hooker House was originally built in the 1720s and served both as a tavern and residence in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. The house has been renovated several times and its restoration in the last 30 years reflects the lives of those who lived inside.

Recently the house has been in the news with the naming of the new middle school after an enslaved man Bristow who bought his freedom in 1775 from the owners of the house, Thomas Hart and Sarah Whitman Hooker. Hooker’s house was also used as a prison for Tories during the American Revolution.

In 1807 Sarah Whitman Hooker added on to the house and the changes were made in the Georgian style of architecture. The central chimney was taken out and two chimneys were put in, producing a central hallway with two rooms on each side. The roof was rebuilt to add a full second floor. This house has been restored to a time period in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. On the house tour, you will be invited into the first floor.

The Noah Webster House is restored to the year 1774 and represents a classic two-over-two colonial saltbox. In the 18th century the Websters owned 80 acres of land stretching west down the hill from Main Street.

Though only a few of the present furnishings actually belonged to Noah, the house has period furniture which shows the difference in lifestyle 230 years ago. In this house, compare the “new” lean-to kitchen and fireplace from the late 18th century, which was built to save on wood and heat, to the original. Notice how the furniture is moveable and how rooms served more and different purposes than they do today. The new reproduction kitchen allows the museum to continue to be a hands-on museum without further endangering the original house.

The third house, and one of the three private homes to be opened, is the Benjamin Colton House at 25 Sedgwick Road, built in 1769. This was built by the son of the second minister of the West Division. Reverend Colton was the minister of the first church in the West Division from 1713-1759. His first son George and grandsons Chester and George became ministers in other Connecticut towns.