Post-World War II Era

Shelter from the Storm

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, December 2011

Conard High School’s transformation into a shelter from November 1 to 8, 2011, marshaled many town and social services to care for more than 350 people who visited the shelter daily. This unprecedented use of the school during the natural disaster caused by the early snowstorm made me wonder how the town dealt with the flood in 1955.

West Hartford’s response to the ’55 flood got tangled up in World War II housing which the town had been trying to demolish for four years.

The Lanham Act, passed in 1940, permitted the use of federal funds to build public housing for defense industry workers. The government shifted from building housing for the poor to building housing for war workers as war industries began to boom. As workers migrated to the cities to take factory jobs, they needed places to live. The federal government made this part of the war effort, suspending traditional public housing construction but expediting the construction of war worker housing administered by local public housing authorities.

West Hartford’s three war housing projects, Elmwood Acres (on Elmhurst Street) with 300 units, Oakwood Acres (where Kennedy Park is today) with 335 units, and South Quaker Terrace with 159 units, (on Quaker Lane near the National Guard) all opened between 1942 and 1943. Oakwood Acres and South Quaker Terrace had a total of 494 housing units. Elmwood Acres consisted of small single-family homes and duplexes that are still inhabited.

According to the Lanham Act, when the war ended, the housing would be torn down. The Oakwood and Trout Brook Acres housing was built very quickly and was not meant to last. And, post-war, towns worried about the developments becoming low-income housing.

Just two months after the war ended, the town appointed an Advisory Committee on the Disposition of War Housing. At its first meeting in December 1945 over 100 South Quaker Lane tenants sought aid from federal, state and local officials who told them they had to move to Oakwood Acres. A spokesman for 40 families at South Quaker Terrace said adult members of most of the families signed a petition that would be sent to Governor Baldwin, Senators McMahon and Hart, U.S. Representative Herman P. Koppelmann and Councilman Cassens.

Among the residents were 11 veterans who felt that moving would be a hardship. Veterans found it difficult to rent, and their advocates argued that those in Trout Brook Acres had not been able to find rentals because of the acute housing shortage.

The Town Council relented and did not tear down the housing projects. Then again in 1951, the town’s Advisory Committee for the Disposition of War Housing met at the Town Hall to map out a request to extend the life of West Hartford’s two temporary federal housing projects. The town scheduled both to be razed by the government in July 1952. Veterans groups continued to be concerned because they were not able to find housing. They asked the government to build permanent low-cost veterans housing, but until then, wanted the town to keep the World War II housing up.

In 1953, once again the Federal Public Housing Administration tried to tear down the housing. But the West Hartford Housing Authority fought it using the power of US Senator William Purtell. At that time, the projects were full of tenants with 369 families on the waiting list. These projects were no small thing for the town. Almost 1,400 children lived there with over 700 school-aged children. The federal government gave another reprieve.

By 1955, the housing was close to demolition with just 78 families still living there and 257 vacancies. Then in August 1955, storm Connie rained five inches and five days later hurricane Diane dropped 14 inches in 34 hours. The flooding began on August 19.

On August 23, 1955, the West Hartford Housing Authority got permission to reopen the units in Oakwood Acres to house homeless families from Farmington and Unionville. Just five days later, 30 flood families moved in with 20 more families on the way. To be accepted into the housing project, all the evacuees needed was a letter from the Red Cross.

While there were no residents left at South Quaker Terrace, the Hannon-Hatch Post took over one of their buildings as a base to arrange to receive and distribute furniture, stoves, and refrigerators. West Hartford welcomed the Unionville residents.

On September 1, the Board of Education voted to admit the “children of refugee families” into local schools. By that time, there were 55 refugee families in the housing project with room for 250 more. Superintendent Edward Thorne thought that the town might have to hire more teachers at Charter Oak and Smith Schools to accommodate these new children. Thorne also reported on problems of our own as the flood had caused washouts at Talcott and Bugbee, and caused boiler room problems at Morley and Smith.

A year after the flood, 15 of the flood families still lived at Oakwood Acres as the town moved to final demolition. Finally in January 1957, the last families moved out of Oakwood Acres and the town demolished the last 10 of 27 apartment buildings and the community building. In its 15 years of existence, a total of 2,803 families had lived there. During that time, according to the chair of the West Hartford Housing Authority, not one family had been evicted.

In some quarters, West Hartford has a reputation for being exclusive; we do pride ourselves on taking care of our own community. But in these two natural disasters separated by 56 years, the town reached out to those beyond its borders. In 1955, West Hartford housed people from Farmington and Unionville, albeit in rickety housing scheduled to be torn down five years earlier. And in 2011, the town opened the doors of one of its high schools and drew people from surrounding communities as well as West Hartford. We should be proud of our commitment to help those in need.

Skiing at Buena Vista

February 2018

When my kids were little, in the 1990s, there were big signs at Rockledge Golf Course disallowing sledding and skiing on a great hill off South Main Street. Now, the town has opened the course in a movement across the country to use parks in the winter as well as the summer.

In the 1940s, the town encouraged skiing and skating in the parks. The town bought the 70 acre West Hartford Golf Club for $20,000 in 1943.

The town used the course as both a summer and winter venue. The Recreation Department set up three ski trails at Buena Vista and provided a first aid toboggan. The West Hartford Outing Club organized activities on a “Practice” and “Advanced” slope. They also helped get the pond in shape for skating.

In February 1945, the ski committee of the West Hartford Outing Club sponsored ski racing at Buena Vista. Elementary, Junior and Senior High boys and girls ran a series of races in February with the hopes of winning an emblem for their ski jackets at the end of the season.

Women await their ski run down Buena Vista hill with the new housing development in the background, circa 1945. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

On the Sunday after Christmas in 1947, according to the Hartford Courant, over 600 people skied on the three slopes. By the second week in January 1948, the town provided lights for night skiing. There was also a hill for coasters and tobogganers.

The Recreation Department offered free ski lessons to both children and adults. By February 12, 1948, the Rec Department counted almost 8,000 skiers and skaters.

At the same time, the town set up a skating rink behind Hall High School (the present Town Hall in the town’s center). The rink was three inches of solid ice on the ground, so parents did not have to worry about their kids falling through. On January 22, 1948, the Rec Department planned to add lights. Students at Hall could skate during gym periods. Residents could also skate at Fernridge Park, Beachland Park and Buena Vista. All three places had warming huts for skaters.

On January 13, 1958, the Rec Department claimed 5,000 people “flocked to West Hartford skating, skiing, and coasting in one of the biggest turnouts in town’s history.”

As late as 1972, the Parks and Rec Department sponsored free downhill ski lessons at Buena Vista.

In 2017, the town has once again opened a golf course to the public in the winter. What fun to go cross country skiing at Rockledge. And, what about opening up some of these ponds to skating? Or having an outdoor rink at some of the parks or schools?

School Superintendent Edmund Thorne

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, May 2007

Edmund Thorne, the town’s third superintendent, headed the biggest school building program in town history. Building eleven new elementary and junior high and high school buildings stands out as the hallmark of his tenure from 1947 to 1964. But beyond the bricks and mortar, Thorne had an educational vision that put the town at the forefront of educational policy and practice.

In 1963, Thorne provided an overview of the changing issues in the schools in a 32 page annual report written for the Board of Education. Thorne’s hopes and concerns about the West Hartford Public Schools reveal much about the town, the state of education, and national trends.

Thorne had much to deal with coming out of World War II. A backlog of facilities problems as a result of putting off maintenance during the war led to replacing coal fired and hand stoked boilers. Town crews replaced roofs and plumbing. Physical plants needed to be repaired. The town not only built eleven new schools between 1949 and 1964 at a total cost of under $17 million, but it also modernized and made additions to nine older schools at a cost of under $5 million. Today, building just one middle school Bristow, cost about $24 million dollars.

The baby boom affected West Hartford more than other towns. A huge boom in desirable residential housing and the drive to live in this inner ring suburb led to the school population growing from about 5,000 in 1947 to 12,000 in 1963.

But Thorne’s interest went beyond finding spaces for the rapidly growing school population. He was also concerned with funding the schools, teacher salaries, special education, honors programs and learning that went beyond testing.

During World War II, teachers’ salaries did not keep pace with industry salaries. Many teachers left for higher paying jobs in the private sector. Teachers with less expertise and experience replaced these employees. Starting pay was $2,100, about $55 per week. The maximum salary was $4,200. Thorne believed in paying for quality. From 1961 to 1963, on the recommendation of a Citizen’s Committee, he awarded merit pay. However, difficulty in its administration led to its suspension. Thorne believed the difficulty in attracting good teachers also lay in a shortage of administrative, supervisory, and clerical staff.

When Lloyd Bugbee wrote his last annual report in 1947, he stated that out of 169 towns in the state, West Hartford was ranked 90th in per pupil expenditure. At the same time, the town was the 18th from the top in wealth per pupil. Thorne believed the town should provide more support for the schools.

According to Thorne, “in 1948 there were no educational provisions for physical, mental or emotional handicaps.” Thorne believed that every child should be educated to the highest level of his potential. In 1952, the first classes for “physically handicapped and “mentally retarded” children were introduced” at Duffy School. Soon after, services were added for blind and emotionally disturbed students. West Hartford led the way in special education.

In 1952, nationally, parents of students with developmental disabilities founded the Council on Mental Retardation to seek services for their children with mental retardation. By 1963, the West Hartford Public Schools offered speech and hearing therapists, and a special reading consultant to improve reading among “retarded readers.” Thorne introduced the first and “still the only special classes in any Connecticut public school system for children with emotional problems.” West Hartford, by 1963, was acknowledged to have “one of the best special education programs” in the eastern United States.

In 1970, U.S. schools educated only one in five children with disabilities and many states had laws excluding certain students including children who were deaf, blind, emotionally disturbed, or “mentally retarded.” The federal law that required school districts to provide education for all children did not pass until 1975.

Thorne, like educators around the country, was pushed by the Soviet’s launching Sputnik in 1957. Public figures criticized the public schools for their failures. In reaction, Congress passed the National Defense Education Act to strengthen the teaching of math and science. Thorne, his administration, and his teachers instituted a number of changes to address the perceived science and math gap. At the high school, new honors courses in all academic subjects and accelerated courses in math were offered for the first time. English teachers were limited to 100 students. Science teachers replaced textbook-centered general science courses with lab-based courses.

The school system received grants to encourage programs for “gifted” students. The high school sponsored a lecture series each year covering topics not included in the regular course offerings. Students had the chance to be involved in the American Field Service exchange program. But Thorne was concerned that the anxiety to act quickly to improve the public school system was pushing creative approaches “based upon a democratic philosophy and long-range goals of what was best for America,” out of the picture.

Thorne worried that teachers could feel as though they needed to teach facts, not concepts. He argued that teachers:

Must teach ideas that provoke thought and lead to further learning and that stimulate critical outlook. Pupils should be encouraged to question facts, seek explanations, anticipate outcomes and question the authority behind a statement or assertion. Students should ask themselves, ‘Is this the truth?’… students should be expected to learn that even scientists make mistakes as well as achieve successes, and that true learning is not achieved through an authoritative body of facts to be committed to memory but through an imaginative way of systematically exploring the unknown.

Thorne placed himself write in the middle of the Cold War ideology when he wrote, “If there is anything that is going to help America survive in the struggle between East and West, it is that of developing creative minds and creative individuals, rather than those who merely parrot back isolated factual information.”

Thorne’s philosophy makes me think about how much the word “creative” has dropped out of the educational lexicon with the present day pressures on testing to ensure that students are learning. How much do external pressures to increase our technological, scientific and mathematical skills make students independent learners and creative thinkers for the 21st century? It seems like Superintendent Thorne would support creative work.

Christmas Carol Sing

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, December 2010

In the late 1940s, the West Hartford Recreation Department and the Chamber of Commerce sponsored a Christmas Carol Sing at the First Church and Goodman Green. On the north end of the green, town workers lit up a “Christmas Tree,” and as many as 5,000 town residents gathered for the sing and an appearance by Santa Claus.

The tradition began in 1930 as an interdenominational carol sing which attracted hundreds of people. In 1940, when West Hartford added a Recreation Department to town government, as Christmas became more commercialized, and West Hartford more affluent, the celebration changed.

Charles L. Rutherford, President of the Chamber of Commerce, rallied many local groups to help organize the first Christmas sing which included the Department of Recreation, the West Hartford Parent-Teacher Council, the West Hartford Exchange Club, the Kiwanis, the Civitan Club, the American Legion, and the Lions Club. On December 21, 1947, organizers expected 2,000 people to come to the 7 p.m. community Christmas Party, Carol Sing and Reception for Santa.

The 20-minute carol sing rang out from the portico of First Church of Christ Congregational. More than 250 trained choral singers from the First Church and St. Thomas the Apostle, and from Talcott Junior High led the carol sing from the portico steps under direction of Gordon Stearns, choir director and organist at the First Church. Two radio stations carried the sing.

Over 4,000 children and adults came to celebrate; the police were temporarily unable to bring “order out of the gaiety.” When Santa Claus arrived with a sleigh that had favors donated by 40 local businessmen, to distribute to the West Hartford children, it was hard to contain the crowd.

Rutherford and his committee wanted to emphasize that Christmas was about giving. His committee wanted to help war-torn France, and with the help of the American Friends Service Committee, they organized a drive for food and school supplies to send to elementary schools in northern France. The AFSC had just won a Nobel Prize for its post war relief work and aided Rutherford’s group in selecting two schools. A West Hartford school administrator sent directions for gift giving to every public and private school student in town.

The 4,000 townspeople who came to the Community Sing brought along boxes of food and school supplies weighing two tons. Helpers packed the goods into duffle bags, took them to the American Legion Hall where they were packed and shipped by the Legionnaires.

The committee arranged for the goods to be sent to the École de Garçons in Caen and the École de Filles Valmy in LeHavre. The Germans burned the Valmy School to the ground a few hours before the liberation of LeHavre in 1944. When the goods arrived in February 1948, the schools still had not been rebuilt and classes were being held in temporary quarters. The head of the school wrote that the children were sons and daughters of laborers who did not have a lot to eat. The packages were well received and many thank you notes made it back to students in their classrooms.

The Carol Sing provided such a positive outpouring of goodwill, organizers geared up for 1948. This time organizers chose to send warm clothing and foodstuffs to “undernourished and ill-clad Sioux and Chippewa Indians in North Dakota.”

In 1948 the choir would have 500 voices. Frank Groff, new music director for WHPS, organized singers from the First Congregational Church, St. James Episcopal, St. John’s Evangelist, a Talcott Junior High School group, Hall High and a select group of 5th and 6th graders.

In 1948, the Chamber spearheaded the community event for a second time. The Christmas Party Committee corresponded with W.M. Simmerman, the Director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The BIA suggested the goods be sent to 1,500 children of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa and the Devils Lake Sioux near Belancourt, North Dakota. In 1948 there were about 33,000 Chippewa, half in Canada and half in the United States. The Sioux were descendants of Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull and lived in poverty on government allotments. Each elementary school student who brought and wrapped a gift, put a sticker on it which read “a Package for a Papoose from West Hartford Community Christmas Party, December 19, 1948.”

The committee in 1948 assured carolers and gift givers that there would not be bad weather because “We live right. That just couldn’t happen to us.” However, the carol sing, which planners thought would bring 5,000, got called off as the town was pelted with 10 inches of snow. The committee collected the gifts and sent them along to the Indians in South Dakota.

Meanwhile, as the snow began to fall in the late morning, the women of the Food for Israel Campaign started collecting packages to be sent to the Holy Land. They collected over 350 bundles that were sent by trailer to New York City to be shipped to Israel.

In 1949 the community supported the carol sing once again. This time, Frank Groff assembled an 800-voice choir from five churches with 600 school children’s voices.

The West Hartford News encouraged townspeople to bring presents of clothing, shoes, toys, infants’ wear, and woolen garments to the children at the Shaw Center in Charleston, S.C., a “welfare center for 1,200 Negro children.”

Since the end of World War II, the naval building program and other war activities were hit hard. The Carol Committee worked with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to find this group. The Shaw Center was made famous as the locale for George Gershwin’s operetta, “Porgy and Bess.”

The invitation in the West Hartford News read “A traditional, gay outing for the Family. Santa will bring favors for the children, and receive gifts of clothing for little Negro boys and girls in South Carolina.”

Rose Wathley, the elementary school supervisor and a member of the party committee once again organized the collection of goods from elementary school children. When the party was first established in 1947, and Wathley was on the committee, she pushed that children truly get more kick out of giving than receiving and it was her suggestion that instead of having Santa arrive at the Carol Sing with sacks of gifts for West Hartford kids, he would come to receive West Hartford children’s gifts for less fortunate boys and girls.

In 1949, the committee had a 30 foot trailer truck at the carol sing so that the gifts could be loaded right on the truck to take the next day to South Carolina to get there in time for Christmas. The trucking company provided the service free of charge. The 3500 attendees donated over 1500 gifts. When the gifts reached Charleston four days later, the Community Center held the biggest party of its kind ever in Charleston. There were three to four tons of gifts. The children, recruited through the Christmas Bureau of the Charleston Welfare Council, were grateful.

This community celebration showcased the varied community groups willing to work together for a common cause. Based on a Christian holiday, these celebrations are certainly the sign of a different time. Though the public celebration of Christmas is as big as ever, and the town encourages Christmas sales with its decorations, its involvement in a carol sing would not be seen as appropriate today. Supreme Court cases in the 1980s discouraged government support of Christian religious displays and West Hartford’s growing Jewish population must have forced elected officials to view its sponsorship differently after 1950.

Regional Plan

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, February 2011

In 1954, insurance giant Connecticut General decided to move its headquarters out of downtown Hartford to suburban Bloomfield. This move mirrored the movement of families to the suburbs. Hartford’s population peaked in 1950 at 177,000 and in the next decade lost 15,000 residents. At the same time, West Hartford’s population grew by 18,000 residents. At its peak, Hartford’s population was quadruple West Hartford’s; now it is about double the number.

Amidst this change, business leaders spoke loudly and clearly about a need for regionalism. In January 1957, the Hartford Area Chamber of Commerce urged towns in the capitol region to become part of a regional planning group. The General Assembly passed a law in 1949, amended in 1955, which enabled towns to be part of such a group. In the late 1950s, both cities and suburbs were willing to talk.

Local governments voted regional planning their number one priority in a questionnaire sent out by the Chamber in 1956. In January 1957, Harold Keith, mayor of West Hartford came out firmly in favor of a regional planning authority. He asserted, “Planning cannot end at the boundaries of political subdivisions.”

In late January, Hartford Councilman James H. Kinsella and Hartford State Senator Harold S. Borden requested that the General Assembly’s Legislative Council study a plan to create a federated form of government in the Greater Hartford area to include the towns of Wethersfield, Newington, West Hartford, Bloomfield and Hartford. The two men recommended that this federated government elect a proportionate common council, a metropolitan board of education, a common tax base and assessment structure, consolidated system of budgeting, financing and purchasing, centralized engineering and public works department, a unified traffic authority, centralized public health and welfare department, consolidated park and recreation department, and a regional planning and zoning agency.

The bill did not pass, but it did not stop the Hartford Courant from running a three-part series entitled “The Challenge: a Study of the Future of Hartford and its Surrounding Communities,” investigating the idea of regionalism. In April 1957, their article looked at the pros and cons of a federated government in Toronto. Senator Burton believed that as suburbs grew, the city could help them, particularly in the realm of schools. He did not ingratiate himself to the suburbs when he said that their fire and police departments “weren’t worth a nickel.” Personalities aside, talk of regionalism abounded.

Almost 300 town officials attended a June 11, 1957 Regional Planning Conference sponsored by Governor Abraham Ribicoff and the Hartford Chamber of Commerce Regional Planning Committee and the Chamber’s organizations in surrounding towns. Participants from 18 towns listened to experts from around the country outline the advantages of regional planning groups.

At the conference, Democrat Ward Duffy, editor of the Hartford Times and West Hartford resident, led a panel discussion with Richard Brown, West Hartford’s Town Planner. Brown argued that small towns would not get swallowed up by the big city in regional planning, but instead “could swing Hartford by the tail.”

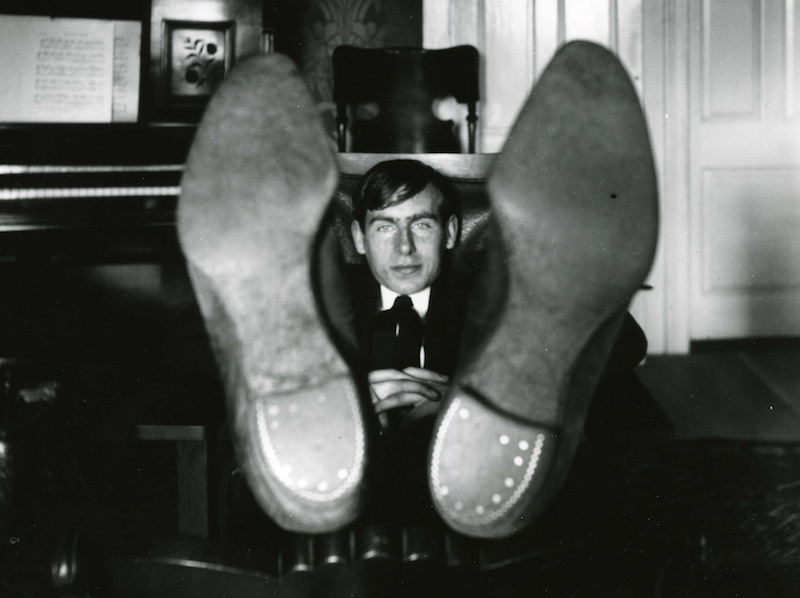

Ward Duffy, editor of the Hartford Times, helped to lead discussions about regionalization in the Hartford area. He and his wife Louise Duffy lived in the Whitman House on 208 North Main Street, in the home where he grew up. His father, Frederick Duffy, was a school teacher, and the head of housing in West Hartford during World War II. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

By November 1957, West Hartford’s Mayor Keith seemed fed up with the state dragging its feet in establishing a Regional Planning Commission, dictated by state statute. The Democratic-led Town Council, the first ever, with the first ever Democratic Mayor from 1955 to 1959, pushed for regional planning for the town. Keith criticized the State Development Commission for not setting up the region for the Hartford area. Keith was particularly concerned about the planning of the East-West highway, Interstate 84 whose route through West Hartford had gone through numerous iterations at this point. On September 10, 1958, the West Hartford Town Council voted unanimously to be part of the Capital Planning Region.

At the same time, the Chambers of Commerce continued their trumpet call for regionalism. In February 1958, James E. Kelley, president of the West Hartford Chamber established a committee representing 11 Chambers in the region. However, he noted, West Hartford was the only town that had endorsed participation in the Regional Planning Commission by that point.

By July 1958, the 22 towns went into the process of voting to be part of the Capital Area Regional Planning Authority. Sixty percent of the towns had to approve the Authority before it started operating. All towns had two votes except those over 50,000. This give Hartford six votes, and three votes each for West Hartford, East Hartford, and Manchester.

The purpose of the authority was to “further the orderly zoning of towns.” It would have a hand in industrial expansion, highway relocation, main park and recreational areas, water supplies, flood control and stream pollution. The planning group was established as an advisory group.

The towns in the Capitol region included Hartford, East Hartford, West Hartford, Windsor, East Windsor, South Windsor, Windsor Locks, Manchester, Glastonbury, Wethersfield, Rocky Hill, Newington, Bloomfield, Farmington, Avon, Simsbury, East Granby, Ellington, Vernon, Tolland and Bolton. By July 1958, Granby voted not to become part of the group. The decision to participate had to be made at Town Meeting.

In November, the West Hartford League of Women Voters took on the issue of regional planning and held three discussion groups at member’s homes throughout town. Two meetings were held during the day and one at night. One of the discussion leaders was Mrs. Richard Brown, the wife of West Hartford’s Town Planner. Another was Joan Kemler who went on to represent West Hartford in the General Assembly. The League wanted dialogue about regionalism and the talk only served to increase support among progressives in town.

Mayor Harold Keith also worked to sell the idea and held meetings during the year with community organizations like the Rotary and Civitans to get them to support the Authority.

When Keith chose not to run for re-election in 1959, he became chair of the CRPA. The Authority received $25,000 in federal funds and so built a two year plan to prepare base maps for the area concerning topography, soil, zoning, development, traffic, transit, public utilities and recreation.

This topic or regionalism came to my attention as I framed a 1959 West Hartford map drawn by the Capitol Region Planning Council. This map included the proposed east-west highway, with an off-ramp at Park Road that went north to empty out at Farmington Avenue. It included the proposed Route 291, which went north from the east west highway right through the MDC Reservoir. This part of the “regional plan” led to protest and its demise in the mid-1970s.

While the push for regionalism in the 1950s came in a time of prosperity when there was a large migration from city to suburb. Today talk of regionalism is a cry from those trying to trim municipal budgets in times of recession. Out of prosperity or recession, the idea of regionalism continues to have its followers.

The Advent of the East-West Highway

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, August 2000

Camp Courant at Park Road and Trout Brook? The Oakwood Gardens Housing Project? Kane’s Woods? The South Quaker Lane Housing Project?

These were all sites in West Hartford on one of the proposed routes for the new East-West Highway in the 1940s and 1950s.

The housing projects have been torn down, Camp Courant moved, and Kane’s Woods developed into a shopping center and apartments. The East-West Highway, now Interstate I-84, takes a more southerly route through town. How did the federal and state government convince the town to engage in this $25 million (in the early 1960s) infrastructure project?

Moves to the suburbs in the post-World War II period, according to most historians, were escapes into conformity and consumerism away from the complexity, activism, and excitement of the city. Americans were happy to retreat to their suburbs with the help of federal housing subsidies for GIs.

But a look at the state and federal governments’ attempt to put an east-west highway through West Hartford reveals a population ready and able to challenge authority. This fight, along with conflicts over building schools in the 1950s, made West Hartford a place shaped by conflict and community activism. Citizens of West Hartford fended off building the highway for more than 15 years.

By 1949, 60% of the traffic that entered Hartford came from West Hartford. The local east-west roads (New Britain Avenue, Park Road, Farmington Avenue, Asylum Avenue, and Albany Avenue) were clogged with traffic and the state felt an east-west highway would help solve the traffic problem. West Hartford’s population in 1950 stood at about 62,000, a leap of over 25% since 1940. The population grew as the insurance industry in Hartford prospered.

West Hartfordites, who fashioned themselves as the residents of an upscale residential community, did not believe the highway was necessary and thought it would split the town in half, and ruin its residential character. The first plans for the highway were floated in 1945. In this plan, the highway would have gone through the center of town. At the first public hearing in 1948, 500 protesting residents showed up, forcing officials to move the meeting from the Town Hall to the Hall High Auditorium right next door. Townspeople expressed strong opposition to a proposed plan that would have sent the highway from Prospect Street at Warrenton directly west running between Boulevard and Farmington Avenue. Just west of the Kingswood School, it would turn south to follow Trout Brook to Taylor Road to meet the highway section from Corbins Corner.

In 1950, West Hartford’s Town Council approved a more southerly route that would have gone from Prospect at Park, through the World War II housing project, Oakwood Gardens (now Kennedy Park), up Oakwood Avenue and through the South Quaker Lane World War II housing. But, the state did not follow through at that time. Planners had as many as eight possible routes for the highway by 1956.

In January 1956, 350 residents met at the Smith School to protest the highway and formed the East-West Residents Association, elected permanent officers and voted to oppose “Plan C” as proposed by the state highway department. Residents believed that widening the main east-west arteries, staggering work hours in Hartford, and installing one-way streets at rush hour in cooperation with the Hartford City Council, could solve the traffic problem.

At a public hearing held at Smith School in September 1956, 300 residents as well as the clergy of the newly built St. Mark’s Parish (1947) protested the highway. The Town Council unanimously voted down the newest proposed route. The East-West Residents Association pushed the Town Council to commission still another study of the proposed routes.

Part of the 1956 plan was to build a connector from the highway at Park Road and Trout Brook north along Trout Brook to Farmington Avenue to improve the movement of north-south traffic. This would have eliminated Norfeldt baseball field, a town garage, two gas stations on the corner of Farmington Avenue and Trout Brook, Bess Eaton Doughnut, a new building containing the Nichols Cordial Shoppe, and Chicken Delight, among other buildings. Trout Brook Drive was still not completed between Boulevard and Farmington. Though residents worried that the opening of Connecticut General Life Insurance Company in Bloomfield on January 1, 1957 would exacerbate traffic problems, they fought at public hearings to stop the connector.

The Town Council appeal both to the Federal Bureau of Roads and the State Highway Department was denied in early 1960. Some local politicians believed they still might stop the road but most realized they could only revamp the plan by that point, particularly what they called then the “butterfly approaches” to the highway which residents saw taking up too much land.

The Federal Bureau of Roads finally approved the east-west highway project in January 1960, 15 years after the first plan was floated. Still, some Town Councilors wanted to appeal the decision because the federal government had not done enough to consider the economic consequences to the town. But the majority of the town was resigned to the highway. The state had already spent about $5 million buying properties along the route.

By 1961, the plan that would have taken 18 homes ten years earlier, now took 144. This led to a loss of $5 million on the town’s grand list. By this time, resigned to the highway, some Town Councilors argued, that commercial property along the route, especially at Corbin’s Corner and Prospect Avenue would increase in value.

Plans moved forward to start construction in October 1962. But there was one more surprise in store for the residents just west of South Main Street and north of New Britain Avenue. Engineers decided that it was too difficult to run the highway over South Main Street. This meant that eight houses on Brightwood Lane would have to be torn down because of the grade of the hill needed when they dug under South Main Street. One of the houses belonged to former Mayor Harold Keith, a vehement opponent of the highway for at least ten years. Negotiations with the state highway department led to building the retaining wall south of the entrance to I-84 on South Main Street. All eight houses were saved.

The highway opened in the fall of 1964. The section from Corbins Corner to Trout Brook was attached to the new section, now known as the “West Hartford Curves” and went as far east as Prospect. The highway was not completed through Hartford until 1969.

West Hartford residents and their elected representatives were not complacent when the state and federal government tried to impose a plan that was perceived as being for the larger good. Residents organized and pushed their elected representatives to use every appeal to, as they saw it, save the character of their town. The calm veneer of the suburb hid a contentious residential population, concerned about the nature of their town. Simultaneously, battles concerning the fate of the World War II housing and building new schools came up yearly as residents fought to define the type of town in which they lived.

A Special Bond between West Hartford’s Jews and Israel

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, July 2008

The Greater Hartford Jewish Federation marked Israel’s 60th anniversary on June 1 with a celebration at West Hartford’s Mandell Jewish Community Center. This celebration marks more than 100 years of support for Israel in the Hartford region.

Ronnie Siegel of West Hartford, the event coordinator, was born in Israel the year it became an independent country. The JCC was a natural place for this event, as it has been a hub for the Jewish community in the Hartford region since 1962.

In Making a Life, Building a Community: A History of the Jews of Hartford (1997), David Dalin argues that the Hartford area was an early and important center of American Zionism. Zionists support the establishment and continuation of an independent state of Israel.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the Jews in Hartford were united about the need for the establishment of a Jewish state. The size and strength of this consensus was unmatched in other metropolitan areas. Dalin argues that:

all members of the Hartford rabbinate, whatever their differences on other religious and ideological issues, shared a passionate and unequivocal commitment to the Zionist cause… Indeed, during the 1940s, Hartford was one of the few American cities with a large and historically venerable German Jewish Reform component in which the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism did not establish a strong organizational foothold.

Perhaps it was the size of the region and its large proportion of Jewish residents that helped to unite the Jews. Dalin suggests it was leaders like Rabbi Abraham Feldman who helped unite all Hartford area Jews to the Zionist cause.

Rabbi Abraham Feldman served Beth Israel from 1925 to 1968. The synagogue was the first to move to West Hartford in 1936. Feldman organized a local rabbinic organization that drew active participation of Orthodox, Conservative and Reform congregations. Source: Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford.

The idea of a “land of Israel” goes back to Biblical times as told in Psalms and is found in the daily liturgy of the Jewish service. The theological ideas of Zion first found a political voice in the late 19th century as nationalism and socialism took hold in Europe.

In 1882, a group of Russian Jewish students went to Palestine, then a part of the Ottoman Empire, to begin an agricultural community.

In 1885, the Jewish Reform Movement in the United States adopted the “Pittsburgh Platform” that denounced building a political nation. The American Reform movement stated that it did not want to be a nation, but instead saw themselves as a “religious community” and did not expect to return to Palestine or establish a Jewish state.

Historically, this position made sense in the context of the late 19th century United States. Jews, and particularly German Jews, had reached a certain point of acceptance in the U.S. They believed that the freedom they experienced in the United States made a separate “Zion” unnecessary.

Isidore Wise is a good example of a man who “made it” in America. He and Gershon Fox, also Jewish, both owned department stores downtown. Wise was the president of Congregation Beth Israel (1907-1942) and owned Wise, Smith & Company, a department store on the west side of Main Street right across from G. Fox & Co. He was president of Beth Israel when the congregation was on Charter Oak Avenue in Hartford.

However, with increased Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe caused in part by continued pogroms in Russia, and more tension even within the Jewish community in the U.S., the ideas of the American Reform Movement began to shift in favor of a Zionist state.

Rabbi Abraham J. Feldman, who served Beth Israel from 1925-1968, was a leader in West Hartford and nationally, and an ardent Zionist as well as part of the American Reform Movement, beginning in his student days. At the University of Cincinnati, Feldman invited lawyer Louis D. Brandeis, a passionate Zionist, to come speak to the Jewish Honor Society called the Menorah Society in 1914.

Brandeis was a leader of the American Zionist movement. In 1916, Woodrow Wilson appointed him to the U.S. Supreme Court where he served until his death in 1939. Even while Brandeis served on the Supreme Court, he worked actively for the Zionist cause.

In 1918, at Hebrew Union College, Feldman challenged the president of the college to debate him on Zionism. Feldman was one of the key local and national players who took on the challenge of uniting Reform Judaism with Zionism. He brought those strong beliefs to town and continued to organize and support Zionism throughout his tenure at Beth Israel.

In 1921, the Hartford Jewish community held one of its first public events in support of Zionism when Chaim Weizmann, head of the World Zionist Organization, who went on to become the first president of Israel, came to Hartford with internationally renowned scientist Albert Einstein. They arrived in a motorcade of 500 cars and 15,000 spectators lined the streets.

Unlike most other cities, Hartford’s rabbis were united behind the Zionist idea. Einstein and Weizmann had lunch at the Hotel Garde and then both men addressed the packed house at the Capitol Theater, which at that time had the largest seating capacity of any theater in New England. The two men raised $100,000 for the World Zionist Organization.

By the time Israel proclaimed its independence in 1948, middle- and upper-class Jews had moved from the Front Street area of Hartford to its West and North Ends and into West Hartford.

Both Congregation Beth Israel (1936) and Beth David Synagogue (1943) had opened in town and Rabbi Feldman established a local rabbinic organization that drew the active participation of Orthodox, Conservative and Reform rabbis, ones with whom he vocally disagreed, but whose unity made the Jewish community stronger.

Unlike other metropolitan areas, the Hartford region’s Orthodox, Conservative and Reform congregations all supported Zionism early on. This support has not always been easy as unrest continues in the Middle East. West Hartford’s united celebration of Israel’s independence in 2008 shows, in part, a long history of Jewish cooperation in the Hartford region.

Schools for Democracy

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, March 2001. Sources include “Histories of West Hartford Schools,” West Hartford Public Schools, 1964, found in the Conard High School Library; David Halberstam, The Fifties (1993); and James Patterson, Grand Expectations (1996).

School buildings and elementary school districts often have been the way people identify their neighborhoods in West Hartford.

Families in the 1920s and 1950s supported their children being redistricted in town as the population surged in each of these decades and new schools were built. The growth in West Hartford’s Public Schools mirrors the growth of West Hartford as a suburb.

Until the turn of the century, most West Hartford students went to one of the eight one- and two- room district school houses throughout the town. Charter Oak School, built in 1884, housed grades K through 8. The first Center School, just south of the Old Burial Ground, was built in the 1860s and housed the first high school students on its second floor. A new Center School (1896) was built as an elementary school and was later renamed Whitman School and then became the police station. The Seymour School (later Smith School) opened in 1915.

By 1920, West Hartford had a population of about 8,000 people, mostly living along the major east west thoroughfares of Farmington Avenue, Boulevard, Park Road, and New Britain Avenue. With the growth in automobile ownership in the 1920s, West Hartford’s population tripled to about 24,000 by 1930. During this decade, eight schools were built in town. Three elementary schools, Beach Park (1926), Morley (1927) and Elmwood (1928) opened in a two-year span. Three junior highs (grades 7 to 9) opened between 1922 and 1931: Plant (1922), Talcott (1922) and Sedgwick (1931) that originally opened as a K to 9 school. High school students moved from the second floor of the Center School to William Hall High School (now the Town Hall) when it opened its doors in 1924.

Both the Great Depression and World War II led to a decline in home building in most of the country, but in West Hartford, the population actually grew by 76 percent between 1930 and 1940. West Hartford land developers built and sold many new homes. Nationwide, housing starts fell from just over one million per year to about 100,000 between 1930 and 1945. During the war, it was difficult for builders to siphon supplies from the war industries to build new homes. When the war ended, the building began. Pent up savings, the baby boom, and highways all led to tremendous growth in West Hartford. West Hartford’s population grew from about 42,000 in 1950 to over 60,000 in 1960.

Between 1949 and 1959, the town built nine elementary schools including:

- Webster Hill (1949)

- Bugbee (1950)

- Duffy (1952)

- Whiting Lane (1954, replacing the old East School)

- King Philip (1955, also a junior high)

- Braeburn (1956)

- Wolcott (1957)

- Norfeldt (1957)

- Bridlepath (1959)

The town built the elementary schools where the developers built the houses. After World War II, developers began mass-producing houses. Before World War II, most builders built about five houses per year. After the war, because of the mass production of houses by men like William Levitt, whose teams of men could build 36 houses in one day, 180 per week and 8,000 per year, the pace of building increased.

When Bugbee was built in 1950, it was the only elementary school north of Fern Street and west of Trout Brook. Its district included one-third of the geographical area of the town and was served by six busses. Before 1950, “north end” kids attended Sedgwick or the small Beach Park School. The north end experienced rapid development. Look at the growth in Bugbee’s population over its first 3 years:

| September 1950 - June 1951 | from 365 to 418 students |

|---|---|

| September 1951 - June 1952 | from 529 to 584 students |

| Summer 1952 | 150 students moved to Duffy |

| September 1952 - June 1953 | from 460 to 546 students |

By 1957, the student population settled in around 500 with the opening of Duffy, King Philip, Braeburn, and Norfeldt. In the early 1960s, school officials were nervous about the potential development of the Hunter farm on Flagg Road. They saw this property as having “potential development of embarrassing proportions” if a developer purchased that land. Instead, the town acquired the property which became Westmoor Park.

When Conard High School opened in 1957, the high school population was divided for the first time. Hall High, in the center of town became a “walking school.” All those within a two-mile radius of the school attended. Those who lived in the north and south ends of town went to Conard. These districts did not change until the new Hall opened on North Main Street in 1970.

John Davison, a student at Sedgwick in the 1950s, and a former chair of the Board of Education, remembered his friends being redistricted yearly as Sedgwick became overcrowded and new elementary schools opened. Families moved to West Hartford for a school system that developed a national reputation for excellence. People came from around the nation and the world to view West Hartford’s new schools for both their architecture and their curricula.

In the early 1970s, West Hartford’s population peaked at 70,000 and in the next decade, the town lost 10,000 residents. In the 1970s and 1980s, the town closed several schools. Beach Park School was closed in 1972 (and now is St. Joseph School for Young Children), the Elmwood School was closed in 1975 (and now is the community center), Bridlepath (now Solomon Schecter), and Whitman (now the police station) all closed because of declining enrollment. Smith School closed and then reopened in 1995. Both Talcott and Plant Junior Highs (7th to 9th grade schools) closed in 1979. The two high schools took on the 9th graders and Sedgwick and King Philip became 6th through 8th grade middle schools. The closing of these schools was very controversial. Parents, concerned about which parts of town took the biggest hits, questioned whether schools were closed in the geographical areas with fewest students.

Redistricting in the 1920s and the 1950s did not carry the same political volatility as that of closing schools in the 1970s and 1980s nor of the redistricting in the mid-1990s. Growth in the 1920s and 1950s came with a robust economy and grand expectations. People wanted the best schools for their children, and during these times, the best schools were new ones. Growth fueled the idea that life continued to get better in the suburbs in the 1950s.

Today, parents and politicians look on redistricting with fear and trepidation. They worry that their children will be shuffled from one school to another, a move forced by a redistribution of the population, not necessarily growth. With the state law that mandates that a school’s population cannot exceed 25% above or below the average racial percentage for the town, some parents argue their children are being redistricted for political reasons. But the state and many parents agree that guaranteeing equal educational opportunity for all can only be had if the schools are not racially isolated. This, the state argues, is part of the foundation of democracy.

The Korean War

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, June 2005

The Korean War armistice was signed on July 27, 1953 and when the news made it to Hugh Campbell, the manager of the Central Theater in West Hartford Center, he interrupted the film that was playing and joyfully announced the truce.

The next day he and his wife got a telegram from the Defense Department. Their son Raymond B. Campbell, aged 23, was killed in action on July 24, 1953, just three days before the armistice.

Campbell was a heavy machine gunner in the Marine Corps and enlisted in March 1951, nine months after the war began. He worked at Pratt and Whitney Aircraft after attending Hall High School. Campbell left his mother and father, and seven siblings. His brother, John was in the Army in Korea.

Like other wars, West Hartford felt the effects of the Korean War through the eleven men who died over a span of five years. The average age of those who died in the war was 24, with the youngest 20 and the oldest 30. Four of the eleven men were married and three had children. Seven of the eleven men died in hostile action. The U.S. suffered about 33,000 combat deaths and 20,000 from other causes. West Hartford men died in about this same ratio.

During the Korean War, 1.5 million men, 18 to 25, were drafted; another 1.3 million volunteered, primarily for the Navy and Air Force. The Korean War grew directly out of the division of Korea in August of 1945 into Soviet Union and the United States occupation zones. Both the Soviets and the Americans believed that Korea should be independent at war’s end, but needed to be occupied because it was not yet ready for self-government. When the Soviets entered the war against Japan on August 8, 1945, two days after the U.S. dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, some Soviet troops entered Korea and a week later, Truman and Stalin agreed that the Soviets would occupy the area north of the 38th parallel and the U.S. would occupy the area south of that line.

In 1947, a United Nations resolution called for elections in Korea to create an independent government. The Soviets would not allow for an election to take place in the north and they installed communist Premier Kim Il Sung as leader, while Syngman Rhee was elected President of the south.

On June 25, 1950, North Korean troops, many fresh from the communist victory in China, attacked South Korea. United Nations forces, of which the United States made the majority, fought back. By the end of September, UN forces approached the 38th parallel. In October, UN forces crossed into North Korea.

The Chinese said they would enter the war if the UN forces moved into North Korea. China entered the war in late October 1950. When MacArthur ordered an “end-the-war offensive” in November, it was met by a Chinese offensive which renewed the war. These offensives forced the UN ground forces south for two months. It was this battle that led to the first three West Hartford casualties.

Kenneth Tackus, 111 Ridgewood Road, was killed in action at age 23 when he was fighting near the Chosin Reservoir in North Korea, December 1, 1950. He was in one of the infantry divisions which reached the Manchurian border in the northeastern part of Korea just before the Chinese attacked. Tackus went to Hall High and Fishburne Military Academy where he was valedictorian of his class. He graduated from West Point in June 1950 and was married the following day. He left behind his wife and his parents in West Hartford.

Bernard Kelly, of 75 South Street, was reported missing in action on December 2, 1950 in fighting around the Chosin Reservoir in Korea and the retreat to the Hungnam beachhead. He was in a heavy mortar battalion. His parents last heard from him on November 17, 1950, but were not told he was missing in action until February 1, 1951, two and a half months later.

Kelly enlisted in the Army when he turned 18. He went to West Hartford Schools and was employed at the Royal Typewriter when he enlisted. Three of his brothers served in World War II.

Gordon “Pete” Kuehner, Jr. of Farmington Avenue was the pilot of a B-26C based at Kunsan Air Force Base (K-8) en route to a target on a night intruder mission when his aircraft was lost on December 28, 1950. He was 28 when he died. This was the third time his mother received such a telegram. During World War II, her first telegram informed her that her youngest son Dick was killed in a fighter plane over France. A second telegram told that Pete was missing in the Aleutian Islands. This telegram was nullified when he was picked up by the Russians. His mother had hope, in February 1951 that her new telegram would be nullified as well.

Kuehner was married and had a three year old son who was named after his brother Dick, killed in WWII. His son Dick wouldn’t learn for sure that his father was dead for another three years. His wife and son were with him when he was stationed in the Philippines before the war in Korea broke out and Kuehner volunteered to go fight.

Kuehner’s last letter, delivered with the telegram, said “How long can a guy’s luck hold out? Well, I’m sure I want to fight this war here, not in the United States, not where those I love might be hurt.” Kuehner’s letter outlined the beliefs of the time of those fighting the Cold War.

In early 1951, MacArthur pushed to attack China. In April, Truman fired him. Washington’s objective was to restore the status quo.

Donald Sirman, aged 29 of Van Buren Avenue, died on June 14, 1951. He was the pilot of an F-80C Shooting Star fighter interceptor while on a combat mission and was shot down by North Korean anti-aircraft fire on July 7, 1950. He survived the crash and was taken a Prisoner of War. His parents knew he was alive because his name and picture were used in North Korean propaganda broadcasts. He died while a prisoner less than a year later.

Truce talks began in July 1951. Diplomats decided to split the country at the battle line, but could not resolve the issues over prisoners of war like Donald Sirman.

In 1952, the war continued mostly as air strikes on North Korea. At least 2 million Korean civilians and one million soldiers were killed. As many as one million Chinese may have been killed.

Frank E. Woodcock, aged 24 of 1199 New Britain Avenue was killed in action on August 17, 1952. He was a veteran of World War II and a member of the active reserve. He held a degree from the University of Vermont. He was employed by Niles Bement Pond before being recalled to the service. He left his wife and a 9 month old son in Elmwood, and his parents and four siblings in Vermont.

Robert Wegner of 127 South Quaker Lane, aged 22 died two weeks after he was wounded from a mine explosion on October 29, 1952. After the injury, he had his left leg amputated and was in danger of losing his right leg. He died about a week after the amputation. He was a football star at Hall High and attended the University of Connecticut for two years. He enlisted on his birthday in 1951 when he turned 21.

Like the other wars, West Hartford’s war dead mirror the action in the war. By knowing the men from the town who died, it makes us remember the cruel and ugly realities of war. Knowing the houses that men lived in, where their children grew up without them, and the fiancés who lost their lovers makes us think of this ultimate sacrifice. Some argue that brutal wars like in Korea keep there from being war again. Larry Phillipon’s ultimate sacrifice in Iraq at the beginning of May 2005 reminds us that the young, brave and strong continue to die for their country and that the effect of the pain at home seems never to diminish.

West Hartford’s U.S. Senator William Purtell

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, January 2007

On July 29, 1959, Republican Senatorial candidate William Purtell addressed 150 women who belonged to the Hartford County Women’s Republican Association in Avon. He said women have the major influence in controlling the nation’s economy due to their role purchasing consumer goods for their homes. He then urged them to get involved and exert influence in political activities on the same level.

William Purtell’s awareness of women’s role in government surely came from his sister, Edna, who was the youngest suffragist at age 19 to go on a hunger strike with the National Woman’s Party in Washington. The suffragists were arrested in front of the White House in 1918 chanting, “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” Over 30 years later, Edna, who never married, still lived in West Hartford as did her brother William.

Born in 1897, William Purtell grew up in a poor family in Hartford and left high school after only two years. His first job was in a rail yard. This led him to his second job which was scheduling wartime rail shipments to Colt’s Firearms.

Purtell enlisted in World War I in 1917. Upon his return to West Hartford, in 1919, he spent ten years as a salesman. In September 1929, at age 32, he founded the Holo-Krome Screw Corporation. On the day the stock market crashed in 1929, Purtell and his two co-owners turned out their first innovative socket screw. No longer was a screw machine needed to produce these parts which made their production much less expensive. Purtell soon secured a patent for his cold-forged socket screw which allowed for the mass production of high tensile alloy steel socket screws.

Founding the company at the beginning of the Depression was not so easy, but early on Purtell realized that his company’s fortune was tied to his workers. He held his employees in high regard and they willingly took short paychecks at times when the company was in financial trouble. Purtell’s company introduced one of the first profit sharing programs for workers in the country. A breakthrough came for Holo-Krome when they sold the socket screw to Detroit’s auto manufacturers, putting the company on firm footing.

In 1936, Holo-Krome, with 40 workers, moved to Newington Road. By 1938, the company was doing so well that Purtell bought Billings and Spencer, a tool and forge firm. The company became a supplier of military parts during the Second World War. By 1946, Holo-Krome became a subsidiary of Veeder Root, a larger company that Purtell later headed. He also served as president of the Connecticut Manufacturers’ Association and as a director of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Purtell was known for his speaking ability. He helped organized the American Legion in Connecticut and spoke on their behalf. He used his speaking engagements to talk about how solutions to social problems should be solved by private initiative. Only after the private sector tried to solve the problems, should the government step in. According to Jack Zaiman, the Hartford Courant political writer, Purtell was a great campaigner because he “was an industrialist, with a vibrant, peppery, glad-handing approach.”

In 1950, the Republican Party came to Purtell asking him to run for Governor. He said he did not want to run, but when they chose John Lodge, he changed his mind and went into the convention looking for the nomination despite the leadership backing Lodge. His skills as a speaker endeared him to many voters as he traveled around the state to garner delegates. But he lost the Republican nomination to John Lodge who ended up winning the election. Purtell continued to run his business, but kept his interest in politics

Connecticut’s Republican Governor John Lodge made amends with his adversary when he appointed West Hartford’s Purtell to the U.S. Senate seat after Brien McMahon of Norwalk died in office in the summer of 1952. Purtell was already running for the open Senate seat — he had won the nomination against Prescott Bush who was supported by the party. Prescott Bush (R) defeated Abe Ribicoff (D) in the November election for this seat and Purtell defeated incumbent Senator William Benton for the other Senate seat. In the course of six months, he held both of Connecticut’s Senatorial seats.

Purtell was an independent Republican who kept the party at arm’s length. During the campaign, Wisconsin’s Senator Joseph McCarthy came to the state and spoke in Waterbury. Purtell did not appear with McCarthy, spurning his help. To voters, Purtell represented “clean independence, unmarred by political clichés.”

Purtell was most proud of his aid to deaf children and help to low income groups. Even though he saw his political career as “less than successful,” he had numerous accomplishments. He served as member of the Labor and Public Welfare Committee and the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. He served on subcommittees which dealt with juvenile delinquency, welfare and pension plan legislation and health. One of his most important assignments came when he was appointed by then Vice President Richard Nixon to the select committee to investigate lobbying. He was also an official observer at the United Nations Atoms for Peace conference in Geneva in 1955.

As a businessman, Purtell believed in “competitive capitalism” to solve the social problems of the day. In a speech before Jewish war veterans in 1956, he urged the private sector rather than the federal government to take care of social problems. In this way, Purtell argued, capitalism would always win out in the Cold War over communism. In 1956, Purtell traveled to Russia to try to open up investment opportunities for American businesses. Purtell also voted for price supports for tobacco farmers.

Purtell was viewed as a liberal Republican who supported increases in foreign aid, particularly to fight communism. He also supported a reduction in the age for women to collect Social Security to age 62. He protected the rights of children in urban areas in relationship to their rights to Social Security.

In 1956, at the Republican Convention, there were rumors that Purtell would run for Governor in 1958 against Abe Ribicoff, but he did not choose to do so. In an interesting turn of events, Purtell’s sister Edna was hired by Democratic Representative Tom Dodd to head his office of women’s concerns.

When Purtell ran for reelection in 1958, Democrat Thomas J. Dodd who lived on Concord Street in West Hartford defeated him. The circumstances for a Democrat were ripe in 1958 as it was the midterm election during a Republican presidency. Dodd was a real politician who worked the Democrats in the state. Purtell tried to attack Dodd on his record, without doing much to stand on his own record.

Back as a private citizen, Purtell ran a small machine tool shop in East Haddam. Bill Purtell died at his home on 6 Arlington Road at age 81 in 1978.

Purtell’s background as a business owner and his great speaking ability led him to success in politics. Though he never finished high school, he never felt that citizens should see that as something to emulate. Purtell never wanted to downplay the importance of an education and wrote a letter to the editor claiming that times had changed so much in the economy that he should not have been looked at as a role model for that reason. He continually stressed the importance of a good education for all citizens.

Public Art in West Hartford

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, August 2008

The West Hartford Art League is sponsoring Art Walk in September 2008, and as part of their celebration will include a self-guided public art walk. Though the concept of public art is not new, the local government’s sponsorship of the recent Busby sculpture “Bear,” denotes a change in public support for public art. The addition of a Charles Perry sculpture on the corner of South Main and Memorial Drive and the installation of a kinetic sculpture by Tim Prentice by the West Hartford Art League’s pond this fall will continue the partnership between the West Hartford Art League and the Town of West Hartford.

What is the history of the town and its public art?

A good first stop on a public art tour through the center is the Old Burial Ground. West Hartford’s first manifestation of public art can be seen in the two cemeteries on North Main Street. The Old Burial Ground, less than an acre in area, set up in 1719, has stones dating between 1725 and 1869. There are 137 markers there. Look at the art on the pre 19th century gravestones. The Stancliff Shop in Middletown probably made James Watson’s stone. The floating punctuation, the uppercase lettering and the rosettes on the shoulders of the stone are all signatures of this shop. Stancliff popularized the rosettes’ use on stones.

The stones of Benjamin Colton (1713-59) and Stephen Keyes may have self-portraits on them. Lt. Joseph Gillitt’s gravestone has a skull, which reminded those who looked of death and resurrection. Gillit was one of the first 29 people to establish the church in the West Division in 1713. Find Rachel Marshfield’s stone in the southeast corner of the burial ground. Her stone has an hourglass showing that time had run out. It has two flowers, one alive, and one dead and severed by a scythe, showing the frailty of life.

In the 18th century, the church and the government were one and the same. Town meetings were held in the meeting house/church; landowners paid property taxes, which supported the church. Though individuals paid for their own headstones, the church/local government took care of the burial ground.

The Old North Cemetery, just north of the Old Burial Ground, next to the Baptist Church, is almost seven acres. Established in 1790 when the Old Burial Ground was filled, the cemetery still allows some descendants of those buried in this cemetery to be interred there. The monuments in this cemetery show the development of gravestone art. Gone are the death’s heads and poems to be replaced by standards like the urn and the willow tree. In this cemetery you’ll find a large monument to those who fought and died in the Civil War.

As the town turned from a farm village into a suburb, the number of public buildings increased. When Hall High was built in 1924 and the Town Hall and Library in 1936, there was also talk of public art. In December 1935, Walter O. Korder (1891-1962) was commissioned to paint his Connecticut History mural at Hall High School. He was one of 76 artists in Connecticut employed by the federal government’s Works Progress Administration (WPA). Two artists, Philip Smith and Francis C. Thwing were hired to assist.

It was not until 1947, however, that Korder completed his Connecticut murals. Korder began painting, but stopped when wartime conditions made it impossible to get the necessary paints and supplies to complete his work. He had to suspend the work for six years. The murals show Connecticut history from the Vikings to the hanging of John Brown in 1859. Some scenes include the landing of Thomas Hooker and his party in Hartford, the signing of the Connecticut Charter, and the founding of Yale. Korder was a legendary art teacher in West Hartford and by 1947, past president of the West Hartford Art League.

Korder’s paintings hang in two other public buildings in West Hartford. He has two paintings at Charter Oak Academy, one of Hansel and Gretel at the witch’s house and the other Winkin’, Blinkin’ and Nod, both painted in 1931. At Conard, Korder’s portrait of Frederick U. Conard hangs in the library.

While Korder was painting his mural, the public private collaboration on the Noah Webster statue was fraught with difficulty. Korczak Ziolkowski’s (1908-1982) Noah Webster statue was just recently refurbished and moved several hundred yards north on South Main Street to act as a beacon to Blue Back Square. As part of the agreement between the town and Blue Back Square, the developers paid for refurbishing this statue of West Hartford’s favorite son.

West Hartford’s Town Council officially supported Ziolkowski’s carving of Webster. In an October 1940 news article in the Hartford Courant, the reported said “Town officials may acquire the marble portrait as a memorial.” Town leaders including Superintendent of Schools Lloyd Bugbee, Rev. Elden Mills of the First Church of Christ and the pastor of St. James Episcopal Church George Guiness all inspected a model of the statue at Ziolkowski’s house. By February 1941, Mrs. Russell Z. Johnston, chairman of the Noah Webster Sculpture Commission reported that she had received 700 contributions to pay for materials and labor of about $17,000. Those who canvassed the townspeople “reported that residents were very enthusiastic toward the project.”

Governor and Mrs. Robert Hurley who lived at 99 Outlook Avenue at the time, headed the list of sponsors. By May, the committee had raised $4,000 and Ziolkowski agreed to go ahead with the statue. Though the Town Council approved the plan and the placement of the statue on the new Town Hall’s lawn, they did not help monetarily. Ziolkowski donated his services and used the money to buy the stone and pay his assistants. Ziolkowski carved this classical sculpture from a single 32 ton block of southern marble. Ziolkowski never formally turned over the title for the piece to the town.

For those with good eyes, check the base of Ziolkowski’s statue where he decries the lack of support of the town. On one of the sculpted books at the base, Ziolkowski wrote: “For you I labored not for my own day, that by the word, men should know brotherhood. My Fellow Men! You have not understood, since each of you would go his separate way.” What began as a united effort by the town government, an artist, and the town’s residents ended with a lasting reminder of the tension over this piece of art.

The public enjoys works of art and the West Hartford Art League continues to advocate for more public art. In tough economic times, the Town Council weighs each penny of public money it spends, and that seems to be no different than it was 65 years ago.

Korczak Ziolkowski and his wife, Ruth Ross, sculpt the Noah Webster Statue in 1941. Here Ziolkowski is carving his message to the townspeople, setting in stone his feeling that those in town did not understand what brotherhood meant. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

A Layman Looks at Schools in West Hartford

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, September 2003

Now, in a maturing society and a seething world we have come to recognize the imperative need for a wealth of wisdom added to a wealth of raw materials. We are looking to the schools, long accepted and long neglected, to supply citizens possessing greater foresight and leadership. — Bice Clemow, publisher West Hartford News, 1951

In 1950, Life Magazine published a 63 question test that rated public schools. School superintendents throughout the U.S. helped develop the survey.

Bice Clemow, publisher of the West Hartford News, a parent and taxpayer in West Hartford, used the survey to rate each of West Hartford’s 13 public schools and all of the schools scored in the “average” range. Clemow found this distressing, as he considered West Hartford to be “an above average town.” He decided to study why the schools scored as average. Clemow saw improving schools as an answer to the “seething world” he refers to in his 1951 quote.

In 1951, Truman was president, the Soviets had detonated an atomic bomb, Mao had won the civil war in China, the Korean War broke out, all part of the Cold War. Senator Joseph McCarthy alleged that there were communists in the State Department. Amidst these internal and external attacks on democracy, many Americans felt that the public school system was the place to build democracy and be sure that citizens knew what freedom was. The better the school system, it was thought, the better the citizen.

West Hartford’s population grew from 24,941 to 33,776 between 1930 and 1940 and then to 44,402 by 1950. That represents a 76% increase in population in that 20 year span. Yet between 1931 and 1949 there were no new schools built. West Hartford Schools were at a space crisis in the 1940s and early 50s, and despite this, young families with children continued to move to the town.

The pressure mounted on the Board of Education to build schools. In 1943, 5,265 students attended the public schools. By 1953, 8,507 attended public school, a 62% increase in 10 years. By 1958 the school population had doubled to 11,563. School children made up 15% of the population in 1943 and 19% of the population in 1958. Families with children chose to move to West Hartford.

By 1951, Clemow believed that the townspeople needed to look a bit more closely at the public schools. He applied the categories of the Life survey by surveying the town’s school buildings, teachers, curriculum, and public opinion. His report, published in four installments from January 25 to February 15, seemed designed to drum up public interest in improving the schools.

Clemow found that the facilities were kept clean, but, he found them lacking in public hygiene. The East and Whitman schools did not have provisions for students to wash their hands in the bathrooms and in many schools there was not reliable hot water or soap. He was very concerned with physical education — wanting there to be a gym and proper locker room facilities in each school. These did not exist except to a primitive extent in the high school. Each school had an auditorium, but some were too small to seat the whole school. The two new schools, Webster Hill and Bugbee, had auditoriums big enough to use as community facilities. He also found laboratory space to be “pitiful. In a scientific age, we are not measuring up at least in facilities… I am just saying that we haven’t a school plant — speaking of all 13 buildings — to match the homes along (to pick a street) Walbridge Road.”

When assessing the role of teachers in the school system, Clemow believed that higher salaries would bring better teachers. In 1950, there were 250 teachers in the system. Teachers in 1950 started at $50 a week, or $2,000 per year. Top salary was $84 per week or $4,800 after 17 years of teaching and 6 years of college training. With the cost of living rising, Clemow argued, the town needed to match teacher salaries with equivalents to the business world. This would keep morale high among teachers. Top salary at that point for a teacher was, “something less than a bus driver makes.” West Hartford made Life’s minimum starting wage. Until the 1950s, the town believed that the secure nature of a teaching job was enough to keep teachers in town, but Clemow believed that promising security was not enough.

The survey also pointed out shortcomings in teacher training. Clemow was concerned that it was difficult to graduate from a liberal arts college and go into teaching. The teachers colleges seemed to have a lock on teacher training in the 1940s and 1950s. Clemow supported a liberal arts education and continuing education in subject matter for teachers. Clemow also criticized the lack of a teacher evaluation system.