Colonial Life

King Philip: Why Did We Name a School After Him?

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, August 2002

According to Harvard historian Jill Lepore, in her book The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity (1998), the war was “always brutal and everywhere fierce” and it “proved to be not only the most fatal war in all of American history, but also one of the most merciless.”

Why, then, did our town, in 1955, name a school after the Wampanoag Indian King Philip? The war devastated both Native and English settlers from 1675 to 1676, with casualties greater than any other war in American history in proportion to population.

The simple answer, according to a Board of Education action in 1955, was to change the name of the King Philip Drive school to the King Philip school. It was named after the street on which it was located.

But why would a real estate developer choose King Philip, also known as Metacomet, as someone to honor in the 1950s? Why a Wampanoag Country Club? Why Mohegan, Seminole, Pontiac and Tecumseh Drives?

This fascination with Indians and what they represent begs some historical investigation.

Between 1620 and 1661, Phillip’s father and Wampanoag sachem Massasoit maintained a stable relationship with the English, but those peaceful relations deteriorated quickly after his death. As more and more English settlements became permanent, the Wampanoags were being pushed off their land and they realized their way of life was endangered.

During Phillip’s 14 years as Wampanoag sachem, from 1661 to 1675, the Plymouth colonists with whom he remained uncomfortably allied, mistreated him and his people. Philip was concerned that Massasoit had given up so much land to the English.

He noted that land was taken unfairly, through written documents, and if the English did not get enough land, they let their cattle roam Indian land, or they negotiated with Indians after supplying them with liquor.

Philip also disliked John Eliot’s praying Indians, those who had been converted to Christianity. There were 14 praying towns in Massachusetts. Philip believed this religious conversion was a dangerous thing and knew that the Christianized Indians were subject to the English king and not their own. They also were under the aegis of the English courts.

King Philip’s War began in June 1675 in southeastern Massachusetts after the English settlers hanged three Wampanoag men by the neck not far from Plymouth Rock. These three men, loyal to Philip, the sachem or chief of the Wampanoag, were accused of killing John Sassamon, a fellow Wampanoag.

According to Metacomet’s men, Sassamon betrayed the Wampanoag plan to wage war on the English settlers. A jury of 12 Englishmen and six Christian Indians convicted these Wampanoag men of murder.

By the end of June, Philip and his men began attacking English towns to try to reassert their control in New England. They attacked three towns in Connecticut, the closest to us being Simsbury, burned to the ground in 1676. Legend has it that King Philip hid in a cave on Talcott Mountain just below where people hang glide off the cliff today.

The Nipmucks, Pocumtucks, Narragansetts and Abenakis joined the Wampanoags at various times, depending upon local disputes and Native alliances which had a long history.

From June 1675 to August 1676, Philip and his men devastated 25 English towns, more than half of all colonial settlements in New England. In 18 months, 2,500 English soldiers and civilians were killed, about 5% of the colonial population.

The Wampanoags slaughtered more than 8,000 cattle. The Wampanoags were fierce in their determination to get back the land the English settlers had taken from them over the previous 55 years.

At the same time, the war proved to be disastrous for the Wampanoags. The settlers killed both soldiers and civilians in their attempts to take land from the Wampanoags and their Pequot and Mohegan allies. Five thousand Native peoples, as much as 40% of the estimated population, were killed.

Thousands more died of disease or starvation or were shipped out of the colonies and enslaved in the Caribbean. Even those who attempted to assimilate by converting to Christianity were removed from their towns and kept on barren islands, where many died.

From the accounts written by English settlers in the 1670s, right after the war, there seems little reason to name the school after King Philip. These first historians portrayed him as a brutal and irrational man.

The colonial militia beheaded him at the end of the war, and quartered his body so it could be displayed in four places. His head was kept at Plymouth on a pole for 20 years. English settlers certainly saw Philip as a vicious, threatening foe.

In 1836, William Apess, a Pequot who was the first to write about Philip in a positive light, claimed that Philip was opposed to attacking the English. He wrote that his young warriors were out of his control. He quoted Philip saying “brothers, these people from the unknown world will cut down our groves, spoil our hunting and planting grounds, and drive us and our children from the graves of our fathers, and our council fires, and enslave our women and children.”

Philip was a man who stood up for his culture, according to Apess, and believed that assimilation was destroying his people. There were values in his culture, he believed, worth dying for. Philip fought to defend the rights of his people.

Apess also said “we find Philip as active as the wind, as dexterous as a giant, firm as the pillows of heaven, and fierce as a lion, a powerful foe to contend with indeed, and as swift as an eagle gathering together his forces to prepare them for the battle.”

Philip was kind to his prisoners, including captive Mary Rowlandson who wrote a captivity narrative. Apess portrays Philip as a man who understood the English’s devastation to Indians from despoiling the forest and hunting grounds, digging up their dead, taking away the Indian’s leadership, their enslavement, and all their rights taken away.

Philip’s was the voice that said this oppression and destruction was wrong.

Apess, who wrote around the time of the Trail of Tears, encouraged Native Peoples in the 1830s to “seize the mantle of liberty… We want trumpets that sound like thunder, and men to act as though they were going at war with those corrupt and degrading principles that robs one of all rights merely because he is ignorant and a little different color. Let us have principles that will give everyone his due; and then shall wars cease, and the weary find rest.”

Apess called Philip “the greatest man that was ever in America.” So, from Apess’ point of view, King Philip represented values that many of us accept today as American values: to stand up against wrongs, to support liberty, and to believe that all people deserve respect. It is not clear that the real estate developers or the Board of Education had these ideals in mind when they named the school.

Naming a school after King Philip can make us think about our fascination with war and war heroes. Which side in war deserves our compassion? How do we reconcile our idealistic disdain for war and yet our continued willingness to fight? Extreme conditions often make us think of the essence of the human condition and what it is that makes us human.

The words of Apess can give us a sense of why King Philip was a hero and see why his qualities could be emulated. King Philip’s actions in war can also make us question why the Board of Education chose this name.

Equality and Difference in Colonial West Hartford

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, November 2000

“All men are created equal.” This grand statement appears in the Declaration of Independence written in 1776. Since the writing of the Declaration, Americans have thought a lot about the issue of equality in political, economic and social terms.

Was there equality in the West Division of Hartford (as West Hartford was called before independence in 1854) by 1776? And, did colonial residents recognize economic and social differences?

Landholding is one place to look for differences in wealth. When the proprietors divided the West Division land into long lots in 1671, they distributed it according to how much land each man owned in Hartford. Those who had large lots in Hartford received large ones here. There was no attempt in the move west to equalize fortunes; instead this land division reinforced the economic hierarchy that existed.

At the same time, more Americans had the chance to own land than in England. Proprietors divided the abundant land among all sons in the New World, as opposed to only the first son in England.

A look at colonial homes still standing in town gives a glimpse at the range of house sizes and thus the resources of individual families. A middling farmer built the Noah Webster House at 227 South Main. Built around 1748, the house originally had four rooms built around a center chimney. The Benjamin Colton House (c. 1770) at 25 Sedgwick Road and the John Wells Jr. House (c. 1766) at 505 Mountain Road both are substantially larger than the Webster House. They have five windows in front and two on each side, while the Webster House has three windows across the front and one on each side.

The Gillet house, at 202 South Main Street is one of 18 remaining colonial homes in town. It was built by Asa Gillet, a grandson of Joseph Gillett, one of the first proprietors of the town in 1694. Asa Gillett farmed both sides of Main Street in the late 18th century and he traded with the merchant Joseph Webb in Wethersfield. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

This comparison tells us only so much, however. The houses of the poorest residents did not survive. Those who had not reached the middle-class status of the Websters might have lived in a cellar with a roof, or in a shack that did not withstand more than a few winters. Archaeologists in other New England towns have found the remains of such buildings. We have no sites or artifacts here because larger homes were built over these original, simpler structures. But we can hypothesize that the difference between rich and poor housing was greater than the examples left standing.

Inventories taken at the time of a man’s death, are another way to assess the difference in wealth among West Division residents. Designated townspeople went into the deceased person’s home and listed everything found in each room. Today these inventories can be found at the Connecticut State Library. In the 1770s, the total value of the inventories of eight different West Division families (featured in Noah Webster House educational programs) ranged from about 300 pounds to 1,300 pounds.

The types of goods owned by these farmers did not vary greatly. Most families had a Bible and perhaps one other book in their inventory. Wealthier families had more clothing, more looking glasses and more books. The biggest difference in wealth was the amount of land an individual owned.

The Rev. Nathanael Hooker, the second minister in town (1738-1770) who died at the early age of 32, had a list of books and drugs appended to his inventory, showing his educational background as both a minister and doctor. Though his estate was worth only about 550 pounds, Reverend Hooker had the most social prestige in the town because of his education and his position as minister.

The presence of slavery in the West Division was a clear sign of inequality. At least 15 families owned people of African heritage between 1738 and 1827. We have the names of more than 40 people who were owned. Some bought their freedom, some were freed by the 1784 gradual emancipation law, and some died in slavery. Reverend Benjamin Colton owned what he named a “negro servant,” and Reverend Nathanael Hooker owned a man, a woman, and a child.

Finally, the use of church records can tell something of the social structure within the town. In the late 18th century, there was but one church in town: the Fourth Congregational Church of Hartford. All townspeople had to belong to the church and paid taxes for its upkeep and the upkeep of the town. These records reside in the John P. Webster Library in the First Church (so-called after West Hartford became an independent town in 1854).

In a First Congregational Church booklet from 1913 commemorating the 200th anniversary of the church, there is a description from the 1760s about how people were seated in the church. A church committee assigned those with the highest social, political and economic standing to the pews in the front. Church leaders designated a pew for “old maids” in the back of the church. African-Americans like Page and Lew and the widow of Jude (listed as Negro) were members in full communion of the church. They also sat in the back.

People knew where they ranked by their seating in church.

In a list of “Members in Full Communion” in December of 1764 from the Fourth Church, the only church in town, there is a clear differentiation between people by sex, race, marital status and social status. Titles such as captain, lieutenant and colonel distinguished military men. Leaders of the church were denoted as deacons. That Page and Lew were considered members in full communion at the church, however, is evidence that everyone could be full members of the church.

Gender defined social status as well. Married women, like “Stephen Sedgwick’s wife” were listed as wives, not by their own names. Women considered “old maids,” such as Lydia Smith, were listed with their given name and surname, but many widows were noted as Widow Gillet, without the use of a given name. Where you sat in the pews each Sunday reminded those church goers of the social and economic hierarchy of the church members.

In the 1770s, West Divisions residents saw the difference between rich and poor all around them. But the gap, in a small town like the West Division, was nowhere near as wide as it is today, where multi-million-dollar homes exist not too far from one-bedroom apartments. Yet the abundance of land gave more people the chance to be independent farmers and the chance at a higher standard of living than they would have in England.

And, even with the distinctions between classes, there was a sense of equality of access. All residents had to attend the Fourth Church. All of them traded with John Whitman and Zaccheus Butler. While they were reminded of their social standing in church every Sunday, they all shared the right to vote on church matters, and those who owned land voted on town matters. All West Division residents had certain basic inalienable rights, but they clearly knew their place within the established hierarchy of their small New England town.

America Exposed as a Divided Society

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, October 2005

Hurricane Katrina washing away the veneer of New Orleans, bearing the economic reality of American life, led me to reflect on our own community. How clear were the class, race and gender differences in the West Division at the time of the American Revolution? How did people separate and include one another in this community?

Economically, there was a clear difference in wealth in town by the second half of the 18th century. In 1766, Colonel John Whiting, former Treasurer of the Connecticut Colony, died at age 73. He was cited as the wealthiest man in the West Division. He lived north of Albany Avenue. In April 1768, Timothy Goodman’s house burned to the ground. The Connecticut Courant reported that the house “was entirely consumed, together with all his household furniture, clothes, &c. which were very rich and costly, about 200 bushels of grain, and a considerable sum of money.”

These same men who were amassing wealth may also have had indentured servants and enslaved people and/or apprentices in town. Jude, enslaved by Stephen Sedgwick, ran away in 1774. Bristow bought his freedom from Thomas Hart and Sarah Whitman Hooker in 1775. Once the gradual emancipation act passed in 1784, a number of African Americans appeared in the church records dying in a pauper status.

A number of indentured servants and apprentices were part of the West Division community as well. In 1768, an apprentice about 19 years of age named Moses Cook ran away from Ashbel Wells. Cook “carried away a great coat, a good suit of brown cloth, yellow buttons and sundry other articles of cloathing.” By law, anyone who found him was forbidden from hiding or employing the runaway. Wells did not offer a reward for his return.

September 1784, an 18 year old named Truman Merrill ran away from Samuel Stanley. The advertisement in the Connecticut Courant said Merrill was about five foot ten and was well built with “short curl’d hair.” He worked Stanley’s clothier’s shop and Stanley believed Merrill would try to get work at this trade again. Stanley offered a reward of one shilling and sixpence.

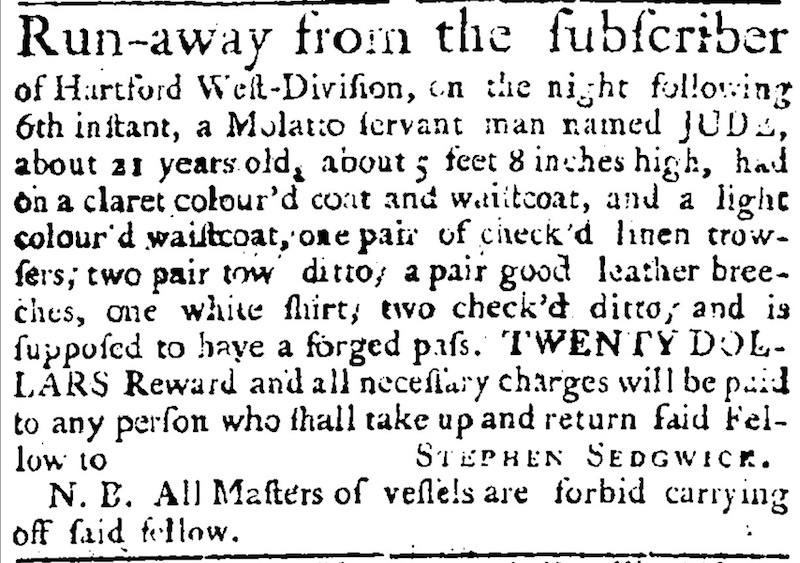

This Connecticut Courant runaway ad, August 9, 1774, is typical in describing what the runaway Jude was wearing and carrying. Note that Jude had a forged pass, indicating that either he was literate or he knew someone who would forge a pass. The owner, Stephen Sedgwick (1731-1792) married three times and had 10 children by his second wife, between 1762 and 1781. When Jude ran, Sedgwick was 43 years old and had 7 children. Source: The Connecticut Courant and Hartford Weekly Intelligencer (1774-1778); Hartford, Conn. 09 Aug 1774: 3.

In 1793, Charles Stedman, a lad of 18 ran away from West Division resident Francis F. Olmsted. A reward of two dollars was offered to the person who returned him. Olmsted described him wearing a London smoke coat, a stitched vest and brown trousers.

As early as 1791, there were ads in the paper about Charles Webster’s store where he had just received a fresh supply of European Indian goods, cloth and crockery ware. A customer could pay with “cash, country produce, tow cloth, linen check, clean cotton and linen rags,” all items produced in the West Division. In 1797, an ad for Webster’s store advertised that he had received goods from New York including broad cloths, plain and figured cashmere, flannels, vest shapes, chintzes, calicoes, satins, Persians, plain silk, and many other types of cloth. He also offered crockery, hardware and groceries.

The ability to trade for goods in the store is a sign that farmers could produce more than they could consume. Their production depended to a great degree on the amount of land they farmed and whether they also had a trade. Still, all 1,000 residents must have felt like they were part of the community.

The availability of land made life in America different than it was in England and spread opportunity around. Yet by the 1750s, land in the Connecticut colony was almost all being farmed. In 1754, Noah Webster, Sr. subscribed to land in Susquehannah County in the northern part of Pennsylvania. A man in Windham organized the subscribers. All the subscribers in the West Division lived near Webster on Main Street. Webster believed this land was controlled by the Connecticut colony because the charter gave the colony a right to all land westward.

The French and Indian War broke out in 1756 and fighting continued to 1761. In 1762, settlement began in the Susquehannah. In 1763, as a result of the Treaty of Paris ending the French and Indian War, the King in Council banned settlement on the Susquehannah land. There was concern among Connecticut’s political leaders about this land. Connecticut had an elected governor and by the late 18th century the citizens feared that this right would be taken away if they caused any trouble and the British in turn would appoint a royal governor like in Massachusetts. In 1769, opponents of of the Susquehannah land felt settlement there jeopardized Connecticut’s Charter which allowed for the citizens to elect their own governor.

The General Assembly replied in 1774, by extending Connecticut’s jurisdiction over the Susquehannah Company’s claim in the Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania. Thus, those who had the means could speculate in land out west, increasing their wealth in relationship to those who could not invest.

Religion provided a sense of community in New England, but it was clearly a hierarchical community. The Congregational Church was the established church; all had to pay a tax for the support of the minister, and it was the only church in town until 1859. The first two ministers of the West Division were Benjamin Colton and Nathanael Hooker. Both men graduated from Yale College. Colton graduated just 13 years after it was founded and became a minister in the West Division in 1714. He served for 46 years until 1759 and earned his fame as a solid preacher.

Nathanael Hooker graduated from Yale in the late 1750s and was hired straight away; he was known to be a brilliant man. He died young at age 33 in 1770. A 1764 list of members in full community at the Fourth Church of Christ Congregational revealed all levels of people who belonged to the church including a colonel, a lieutenant, several captains, deacons, “negroes,” widows, wives, and single women listed by their own names. Anyone could be part of this church, though within it, people’s ranks were clear by the seating arrangement, decided upon by the deacons. Women could be members in full communion, but widows sat in the back and wives were known by their husband’s names.

The Reverend Nathanael Hooker understood that for women’s education, his community could not offer all he wanted for his daughter. For her, he felt, it was necessary to leave the community to get a good education. In his will he wrote that,

my said Daughter Ruth have a better and more polite Education than she can possibly have in the parish of West Division where she was born, and that for this purpose, She be sent to Boston or elsewhere as her circumstances will allow and prudence dictates, and thereby empower her Uncles James and Horace Hooker and her Aunt Eunice Ellery… [to carry out this desire].

For Ruth Hooker, the mores and services of the community would not allow her to develop in a way that her father envisioned so she had to leave.

The community in which she lived did delineate between people by gender, race and class. Clearly many of those divides could be considered even deeper in the late 18th century than they are today.

The Rev. Benjamin Colton and the Great Awakening

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, February 2009

The story of the Rev. Benjamin Colton, the first minister in the West Division, is a story of stability and tradition. He served the Fourth Congregational Church of Hartford here in the West Division for 46 years.

Settlers traveled to attend the First or Second Congregational Church on Main Street in Hartford when the West Division of Hartford was settled in the 1690s. By 1711, local residents wanted to have their own church.

When the settlers applied for a separate parish, there were 27 families with 164 family members here. According to their petition, seven houses had just recently been built, a sign that the area was growing. The petitioners claimed that there was enough land to support 90 families as they tried to make their case for their own church.

Connecticut’s General Court (now known as the General Assembly) granted the West Division the ability to have its own church, the Fourth Congregational Church of Hartford. On February 24, 1713, ministers in the Hartford area ordained Benjamin Colton to become the pastor of the new church.

Colton took on his ministry in the first meetinghouse. It was a plain building, built in 1712, at the site of the Veterans Memorial on the corner of North Main Street and Farmington Avenue. It was a square wooden, unheated building, with a pyramid roof, small windows, small galleries, a wooden pulpit and rough-hewn benches. This building served the church and the town for 30 years.

The new congregation had 29 members. To become a member of any Puritan Congregational church, parishioners publicly confessed their faith. There were 12 husband-wife couples that belonged to the church as well as five men, one wife without her husband and a widow. This group was Colton’s first congregation.

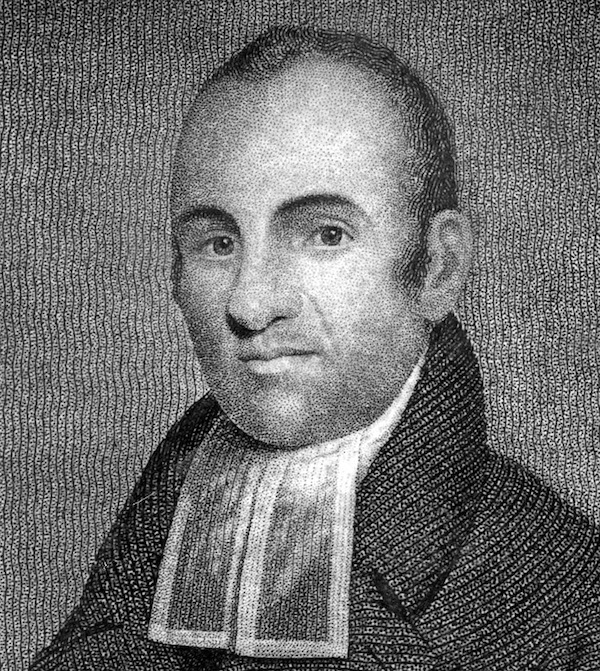

Benjamin Colton studied for the ministry and graduated from Yale College in 1710. He was 21 when he took the pulpit. He was from a family of 18 children and grew up in Longmeadow, Mass. His grandfather emigrated from England.

Colton started as a trial candidate in his position until in October 1713, at age 23, he was hired for a series of years. He married Ruth Taylor two months later. They had four children and in 1725 at age 32, she died. Colton was a widower for about one year. He then married Elizabeth Pitkin and they had five children. Elizabeth had her fifth child at age 47. This growing family became an integral part of the town.

In 1758, when Rev. Colton was 68, church records show the Baptism of “Chris (Negro serv’t of Rev’d Colton).” In that same year, Chris was recorded as “owning the covenant,” revealing he was old enough to consent to being a part of the church.

Colton’s church grew in its early years, as did the population of the town. Not much is known about his preaching, as he only published two sermons. But he was clearly an effective leader, as the congregation kept him on and the church kept growing. The First Great Awakening in the 1730s increased his attendance even more, but led to controversy because Colton was not a supporter of this Great Awakening.

Colton was a religious leader in Connecticut. In 1737, he was selected to deliver a sermon to the newly elected representatives in the new state house that was built in 1719. In his “election sermon” he urged the legislators to get back to God by cleaning up their moral lives. He felt as though there were too many sins including “uncleanness,” pre-marital sex and the enormous amount of rum consumption, particularly among legislators. If, according to Colton, legislators were more moral, they could be more successful. Colton stood up for traditional values.

Even with his colony-wide stature, an outside authority had to come to settle things down at Colton’s church due to the intrusion of the Great Awakening. This religious revival tested the authority of Congregational ministers, their education and their message.

In 1734, Northampton’s Jonathan Edwards began the “awakening” revival, encouraging his parishioners to be more emotional in their faith and put their lives in the hands of God. Conversions were personal, but not public confessions.

George Whitefield’s revival tour in 1740 and 1741 caused a stir. The young English Episcopalian evangelist was emotional, enthusiastic and convincing at his first stop in Boston, where churches seemed unable to contain the crowds that came to hear him. He preached up to 16 times per week. Converts cried out, wailed and jerked their bodies and made the settled ministers uneasy. Whitefield preached in nearby Suffield, East Windsor, Hartford and Wethersfield. Colton and other settled preachers were upset with Whitefield’s invective against settled ministers who had not been taken up by the revival. He denounced their education at Yale and their lack of emotion in the pulpit.

Whitefield’s message was taken even further by the Rev. James Davenport of Southold, Long Island, who in 1742 vehemently denounced the Congregational ministry and in New London arranged for lay converts to burn the symbols of what he thought was wrong with material goods and symbols of learning, including their clothing, ornaments and books.

The Great Awakening moved many of Colton’s parishioners, and Colton and Reverend Wadsworth in Hartford were both worried. But Colton remained in the pulpit, as officials from outside parishes came and settled things down.

The fact that Colton continued his ministry until 1759 showed that there was at least some victory for what were known as the “Old Lights.” His church remained the only one in the West Division until the Episcopal Church in the 1840s. However, it seems clear that he had to change his message to adapt to the ideas of the Great Awakening, even if he didn’t like it.

Colton’s tenure of 46 years at the First Church was a testimony to the importance of his traditional role of the ministry that he learned at Yale. There is no doubt that the Great Awakening jarred him and his fellow ministers, but with their mutual assistance, they sustained the monopoly that the Congregational Church had on religion in Connecticut for at least another 70 years.

African-Americans in the 18th Century West Division

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, April 2001. The author thanks Sally Whipple, who collected these documents when she was director of the Noah Webster House.

In 1893, Bernard Christian Steiner wrote the following in A History of Slavery in Connecticut:

In general, Connecticut has little to be ashamed of in her treatment of the Negroes. She treated them kindly as slaves and freed them gradually, thus avoiding any violent convulsion… Her treatment of the slaves was almost always kind and generous. A master, in true patriarchal style, regarded them as in truth a part of his family. With the coming of the revolution and the struggle of the Colonists for freedom, a feeling arose that it was not just to hold other men in bondage and as a result, importation of slaves was forbidden in 1774.

How much truth is there to Steiner’s assessment of the treatment of enslaved people in Connecticut? Were they treated kindly? Were the slave masters generous? Were enslaved people treated as part of the family and was the slave trade ended because of the ideology of freedom, which was so prevalent during the years leading up to the American Revolution? How did Steiner come to his conclusions?

The Public Records for the Colony of Connecticut, October 1774 reveal a far different reason for ending the slave trade in Connecticut than Steiner offers. “An Act for prohibiting the Importation of Indian, Negro, or Molatto Slaves” starts with the phrase, “Whereas the increase of slaves in this colony is injurious to the poor and inconvenient”… The legislators of the General Court in Connecticut were moved more by economic than political or moral reasons. It wasn’t necessarily about liberty for all.

From the point of view of lawmakers, enslaved people took work away from the poor. Each town was responsible for taking care of the poor and the more enslaved Africans there were, it seemed, the more white poor there were.

“Run-away” advertisements from the Connecticut Courant reveal that many enslaved people chose to flee rather than serve as a slave. In August 1774, Jude ran away from Stephen Sedgwick, a resident of the West Division of Hartford, now known as West Hartford. Jude was described as a “molatto servant man… about 21 years old, about five feet, eight inches high.”

In the West Division, enslaved people were sometimes called servants. Stephen Sedgwick’s probate record confirms that Jude was owned; he is listed in the record as “my Negro Boy Jude” on the line just above “all my sheep and all my swine.”

Perhaps one could argue that Sedgwick was generous to Jude. Jude ran away with a claret-colored coat, two waistcoats, three pair of trousers, a pair of leather breeches and three shirts. He traveled with a forged pass.

Whether Jude wrote the pass, we do not know. Masters describe their property carefully and knew their clothing down to the type of buttons. His wardrobe leads one to believe that Jude was not destitute, but despite Sedgwick’s generosity, Jude reacted in a way that questions whether he was being treated “kindly,” and “as a member of the family.” The owner offered a $20 reward.

There is some evidence of good treatment in the church. John Whiting owned Page, who was listed in the Congregational Church records as a member of the church. Page also had economic power. During the winter of 1740-41, he bought cloth, thread and stockings from merchant John Whitman as recorded in his account book. These transactions lead us to believe that Page actually earned wages and had some economic autonomy. Perhaps this is an example of the master-slave relationship Steiner was describing.

Steiner’s definition of a stable system based on family loyalty was put to the test in the 1790s. With the African uprising and revolution in Haiti between 1791 and 1794, Connecticut residents grew more nervous about the possibility of a slave revolt.

A newspaper article from the Connecticut Courant on September 19, 1791 reported on the “Insurrection of Negroes” in which the Negroes “destroyed all the plantations by fire; that they massacred without distinction every white man in their power; that Negroes are in immense bodies; that they have cut off all communication with any part of the country.” The newspaper reported that the U.S. sent boats to Haiti to rescue the white women and children and to send them to Jamaica or Cuba. Seemingly the fear of slave revolt had to be stronger in the South, where in a state like South Carolina, there were counties with more than 75% African slave population. Connecticut’s slave population made up only about 3% of the total population.

However, in an alarming run-away ad in the Courant in 1794, Charles Churchill, a Wethersfield resident and owner of Jack, “a yellowith Negro who speaks French, Spanish and broken English” declared that Jack was a “cunning, wicked, blood-thirsty fellow who drawed his knife and cut a gentleman.” Churchill went on to lambaste the legislature’s gradual emancipation act of 1784 because he believed freedom would only encourage freed men to cut the throats of the white people, “which would shortly be the consequence as hath been the case in the French islands, where thousands of white people have been cruelly murdered by the same act of liberality.”

This reaction does not seem like the actions of a slave or slave master who had a generous paternal relationship with the slaves as Steiner argues. Joanne Pope Melish in her book, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and Race in New England (1998), argues that before the Civil War, New England’s leaders were pushed to establish an ideology in opposition to that of the South which requires them to forget about their oppression and exploitation of African-Americans.

Bernard Steiner must have used sources of slaveowners, not the enslaved to write his history; diaries of whites, not run-away ads, to establish what seemed like a beneficial relationship for both slave and slaveholder.

A look at 18th-century primary documents reveals a world of tension between owner and owned. Personal rebellion on the part of the enslaved instilled fear in the slaveholders trying to uphold this economic, political and social institution. The West Division was not immune to these tensions.

While all people understood the concept of freedom, not all experienced it.

Whitman on Slavery

June 2018

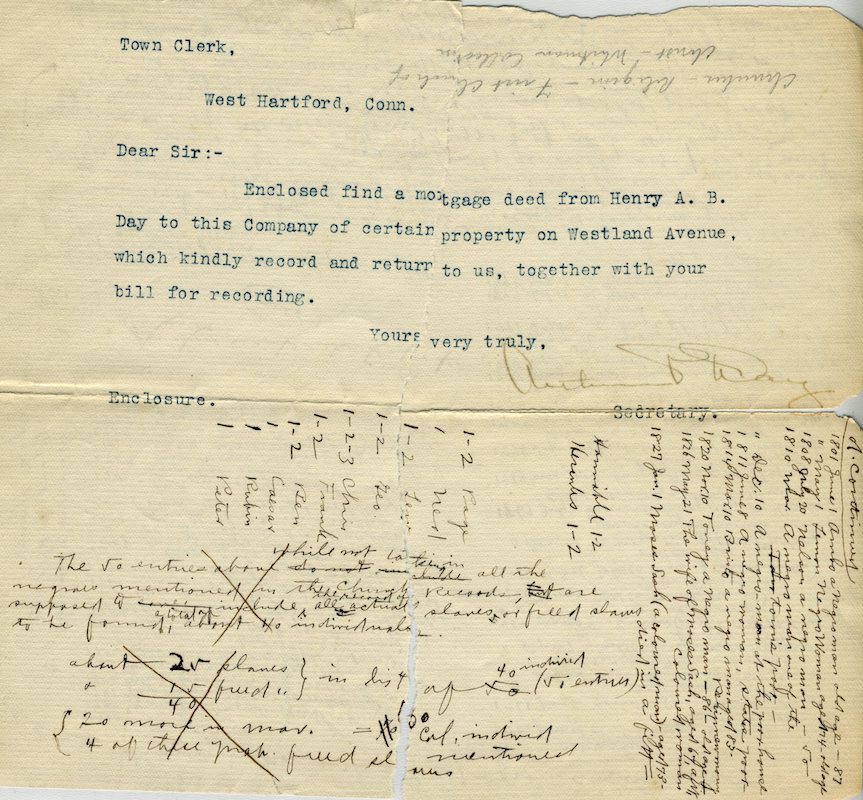

Sometime between 1901 and 1914, West Hartford’s Town Clerk, Henry C. Whitman (1864-1952) made a list of all “negro” Baptisms, Owners of the Covenant, Admitted to the Membership, and Deaths, gleaned from the pages of the First Church of Christ West Hartford’s vital records.

Whitman found that between 1738 and 1827, as many as 50 people of African descent lived in the West Division of Hartford (now West Hartford) and most of them were enslaved. Bristow Middle School (2005) commemorates one of those men. Bristow was part of a larger community of what were denoted in Church Records as “negro servants.”

At the Noah Webster House archives, in the Whitman Collection, you can find this 7 inch wide by 6 inch long legal letter, folded once. The letter has no date and fewer than 50 words. The letter reads:

Town Clerk, West Hartford, Conn.

Dear Sir:- Enclosed find a mortgage deed from Henry A. B. Day to this Company of certain property on Westland Avenue, which kindly record and return to us, together with your bill for recording. Yours Very Truly ,

C?? P. Day Secretary

Enclosure

Town Clerk Henry Whitman compiled this list of enslaved people of African descent who lived in the West Division (currently West Hartford) between 1738 and 1827. Imagine his reaction to identifying over 30 people, two of whom were owned by his ancestors. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

When Town Clerk Whitman received the letter, probably in the early 1900s when Westland Avenue was being developed by Henry Day and his father’s construction company, he filed the mortgage deed and kept the note on his desk.

Then Whitman used the piece of paper to record what had been lost from memory, and possibly what he thought was lost from the story of the town’s past. Whitman not only copied them all out; he analyzed what he recorded.

Many West Hartford residents are surprised to learn that so many people of African descent in the West Division of Hartford were owned by town leaders, ministers, and the wealthier sorts and that so many enslaved people lived here. In 1790, at the time of the first census, there were close to 1,000 people who lived here, in about 150 families. Of those, at least 25 of these families — as many as 15% — owned people of African descent at some point in their family’s history.

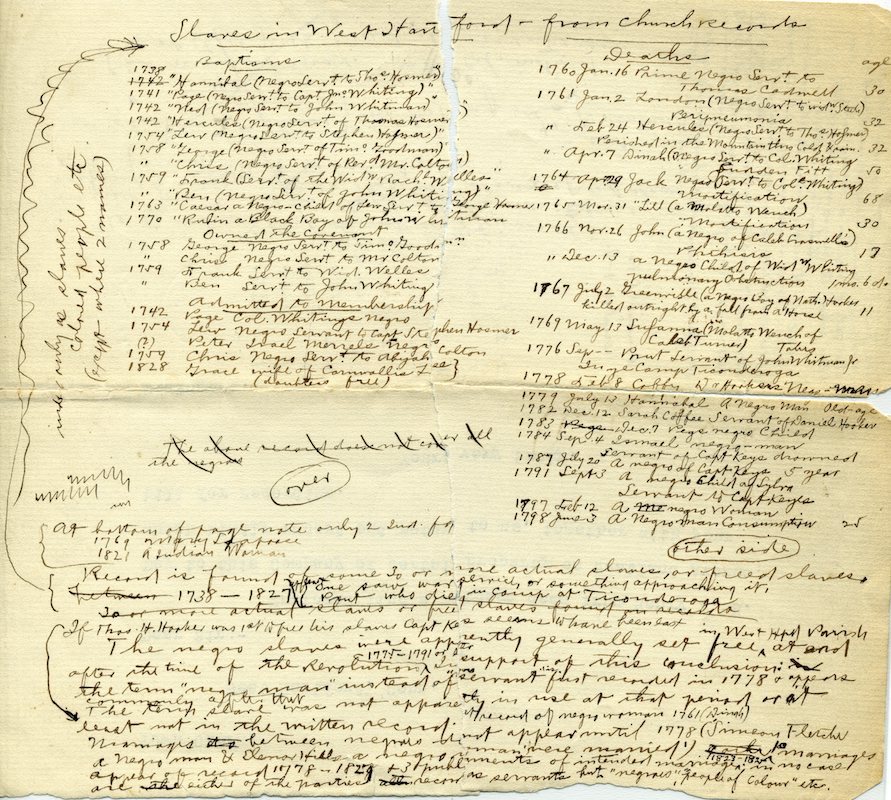

On the back of this letter, under the heading “Slaves in West Hartford - from church records,” Whitman wrote out the names and made these categories:

- Baptisms

- Owned the Covenant

- Admitted to Membership

- Deaths

He listed the names from the church records under each of these headings, documenting men, women and children who were enslaved between 1738 and 1827. In all, Whitman wrote,

Record is found of some 30 or more actual slaves, or freed slaves 1738-1827. At least one saw war service, or something approaching it, “Prot.” who died in camp at Ticonderoga.

The back side of the letter reveals Whitman’s list of names of enslaved people, based on church records. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

“Prot.” is listed under Deaths with the following note: “1776 Sep — Prot. servant of John Whitman, Jr. in ye Camp Ticonderoga.” Here Henry must have stopped when he wrote his own surname, Whitman, realizing that John was his ancestor.

The first in the list is Hannibal, negro servant to Thomas Hosmer, baptised in 1738. Thomas Hosmer was the grandson of one of the first proprietors, also Thomas Hosmer, who owned at least 300 acres north of the center. Just north of where the American School for the Deaf is today, his father, Stephen Hosmer, built the first mill in town. Stephen, according to Town Historian Nelson Burr, “became one of the richest landlords, farmers and traders in the Connecticut Valley.” He became a communicant of the Fourth Church of Hartford in 1725 under Pastor Nathanael Hooker. He married Susanna Steel in 1734. According to Whitman’s notes, his “negro servant Hannibal” was baptized on November 5, 1738. Five months later, in April 1739, Thomas and Susanna had their first child Thomas who was baptised. In 1742, Thomas bought a second man, “Hercules (Negro serv’t of Thomas Hosmer),” who was baptised in that year.

In 1742, Thomas was chosen Moderator of the church and re-elected through the 1760s. He was one of the citizens voted to take care of the schools, and to help build a new school house. In 1757, he took on the label Esq. In 1761, Whitman catalogued under “Deaths,” Feb. 24 Hercules (Negro Serv. to Thos Hosmer), age 32.

In January 1777, Thomas Hosmer wrote his will and died in that same month. In his will, he freed Hannibal:

I have given my negro Hannibal his home and yet by the law he may be chargeable to my Estate if he shall be impotent and unable to provide for himself, if such a thing should happen I order my six sons to provide for his prosperity in equal proportion, but if he be lazie and idle and spend his time foolishly I desire that they will take care that the selectmen will bind him out.

The church records reflect his status as a free man by listing Hannibal’s death as transcribed by Whitman:

1779 July 13 Hannibal A Negro Man Old Age

We don’t know if Whitman actually saw that Hannibal had been freed in copying out these records, if he hadn’t seen the will. But one piece of his analysis leads us to believe he did:

If Thos. H. Hooker was 1st to free his slaves Capt. Keyes seems [to] have been last. The negro slaves were apparently generally set free in West Hfd Parish at end after the time of the Revolution 1775-1791. In support of this conclusion is the term “negro man” instead of “servant” first recorded in 1778 + appears commonly after that.

Why did Whitman transcribe these records? Did he want to know that his ancestors owned Prot. and Rubin, a Black Boy? I wonder if he ever showed the list to anyone or if he shared the information with his wife, his children, or the leaders of the town? Was it only for his own edification, for his own understanding of the colonial world? We do know he kept the sheet and it made it from the church records to the Whitman Collection at the Noah Webster House.

Now the Witness Stones project, begun in 2018, will shine a brighter light on these women, men, and children who have mostly been forgotten. The Historical Society will place markers in the sidewalks at houses where enslaved people lived. These men and women helped build our community and our churches through their work, yet, for so long we only recognized them as property here. Acknowledging the existence of this inhumane system of slavery is a first step in addressing issues of race in our community today. It must have been a jarring step for Whitman as well.

The Sarah Whitman Hooker House

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, January 2005

A house can tell a story. Take the Sarah Whitman Hooker house on the south side of New Britain Avenue east of Main Street. With its beginnings in 1720, it survives today as the oldest structure in the town. The house is owned by the town, but limited access to the house has not allowed its story to be heard by very many people.

The structure was built about 50 years after lots were first divided in the West Division. Split in the late 17th century, people started to move here after the fear of the Indians died away with the end of King Philip’s War (1676). By the 1680s, Stephen Hosmer built a mill on Trout Brook where it crosses North Main and owned 310 acres of land. In 1710 and then again in 1711, citizens of the West Division, 27 families and 164 people, petitioned and got their own church which became the Fourth Church of Hartford.

The Sarah Whitman Hooker House, 1237 New Britain Avenue, was built pre-1740 around a tavern room, probably the oldest section of a building in West Hartford. The home has been used as a tavern, a one family home, a prison during the Revolution, a boarding house, a restaurant and inn, and since 1976, a museum owned by the Town of West Hartford. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society. Date: 1882

Ten years later, John Seymour purchased the land on which the house stands from Stephen Steel. In Seymour’s 1747 will, he mentions his “mansion house on Four Mile Hill in the West Division.” In colonial days this location was called Four Mile Hill — four miles west of the Old State House on the South Road to Farmington.

The structure began as one room with a chamber above and was probably first used as a tavern. Soon after, Seymour added onto it, making it a seven room house by 1747, at the time of Seymour’s will. Seymour’s son Timothy held a license for a tavern in 1733. Next to the meeting houses, the taverns were the most important centers of village life in colonial America.

In the mid-1770s, Sarah and Thomas Hooker moved into the house on the South Road. Sarah Whitman Hooker was the daughter of John Whitman, a prominent town merchant and political leader in the 18th century. The extensive list of household furnishings and goods which her father gave her on her marriage are enumerated in his account book and thus provide a glimpse into the material nature of her life. This account book can be found at the Connecticut Historical Society.

Thomas Hart Hooker went off to war in May 1775, right after the first battle at Lexington and Concord, leaving his wife and two children ages three and five. He died of pneumonia six months later during the siege of Boston.

Bristow, a man enslaved by the Hookers, bought his freedom before his master left to fight. It seems that Hooker also owned a slave named Amboy; according to an 1882 photograph, the house was home to a slave named Amboy who planted an Elm tree on the property in 1769 (cthistoryonline.org). I question the date recorded on the photograph, because it wasn’t until 1777 with the first American victory over the British at Saratoga, that there was a systematic planting of elms in the center of Elmwood by Capt. Ebeneezer Faxon.

During the American Revolution, after she was widowed, Sarah Whitman Hooker was asked to “keep” Philip and his son Andrew Skene, Tories who were taken as prisoners. Hartford had a “Committee Appointed to Take Care of Prisoners” that received their orders from Governor Jonathan Trumbull. Hooker was charged to “confine him on his parole of Honor not to go out of the bounds of Hartford… And provide…[him] with suitable lodgings and entertainment in some remote part of the town of Hartford.” Philip Skene was the Loyalist Governor of both Forts Ticonderoga and Crown Point in upstate New York. The Skenes were native born, not English soldiers. A report in January of 1776 claimed that over 20 people gathered outside the Hooker homestead to harm the prisoners. Purportedly, Hooker calmed them down and they dispersed.

In 1779, Sarah married West Division resident Seth Collins. In the early 1800s, she added on to the house and had the central chimney removed and in turn built twin chimneys on the east and west sides of the house. It is a typical five bay center hall Georgian style home, with clapboard siding and 12 over 12 double hung windows. One chimney has been rebuilt after it was destroyed by fire in the 20th century.

A man named Jedediah Mills lived there in 1807 while Hooker owned the house. He had a taverner’s license for several years in the early 1800s. Still, again in the mid-19th century it became a tavern under the name the Sheaf of Wheat.

In the 19th century, West Hartford remained a farming town. By the mid-19th century, farming became more specialized, particularly in dairy. Just to the north of the house, Charles Beach built his Vine Hill Farm and by 1900, the farm was famous for “baby’s milk.” The Hooker house, then owned by the Beach dairy farm, was used as a boarding house for workers from the Vine Hill Farm.

By the early 20th century, West Hartford transformed into a suburb and the Beach family sold its farm in the 1920s. They donated a good portion of their land to the town in the form of Beachland Park in the early 1930s. Once the farm stopped producing, the Hooker house changed from the boarding house, to a restaurant and inn and that was known as the Sarah Whitman Hooker House.

By 1976, the town of West Hartford owned the house and leased it to the West Hartford Bicentennial Trust to be open to the public as a museum. It was renovated through the efforts of the Fran Fransson family. Her recent death has left the house in the same trust under the behest of her children. The house is on the National Historical Register.

To interpret an historical home, usually the trust decides on a time period, and certainly this house has rich ties to the Revolutionary War period. At the same time, the changes in its structure and use tell much about the history of the town in the 19th and 20th centuries as well. If the house was open more, the citizens who own it could learn more of the richness of the story in three dimensions.

Ye Olde Burying Ground

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, January 2002

Historians have several motives when they analyze artifacts and documents. They try to get a good story from them, have them make connections among people, make them capture a moment, and show how they reflect change. A visit on an afternoon in West Hartford’s Old Burying Ground on 30 North Main Street will provide you with the best light to read the stones and a way to understand the connections and tensions between people in a colonial community.

In West Hartford’s Old Center Burying Yard, whose first burial was in 1725 and whose last was in 1868, there are differences in how the dead were memorialized, depending on wealth and status, gender, race, and era in which they were buried.

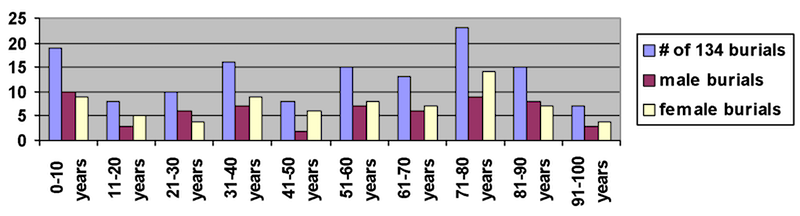

During the Great Depression (in 1934), workers for the federal government’s Works Progress Administration surveyed the 137 graves and recorded their findings. With today’s data base computer capacity, it is easy to make a demographic study of those 137 people (though there are only dates for 134). There are 64 women and 73 men recorded.

The statistics show that life was good in the West Division of Hartford, especially in comparison to what some had left in England, and what some of the first settlers had suffered in the early 17th century. Taken by decade, the most people died in their 70s. Once people lived to be 10, their chances of survival, and even living into their 80s and 90s, were quite high. Thomas Merrell, born in 1714, the year after the first church was erected in the West Division, died at age 100.

Old Burying Ground Burials, by age and gender

Today, more women live into their later years, but in colonial times, this seemed not to be the case, with more men than women living into their 80s and 90s. Many women died in childbirth. Rachel Webster, first wife of Abraham, (the oldest brother of Noah Jr.) died at age 21, in childbirth. Her infant was never named and died after 7 days. While more men than women died in their 20s, more women than men died in their 30s and 40s, perhaps showing that childbirth became more dangerous as women aged.

When you walk into the burial ground, you walk into the “new” section, which has burials from the 19th century. The old section, which is about two-thirds of the acreage, fills the northern section of the yard. You can immediately see a difference in the size of the stones. None in the old section are more than three feet high. The new section has two large obelisks that commemorate the Talcott (of Talcott Junior High and Talcott Mountain fame) and Stanley families. By the 19th century, the idea of individualism had made its way into American society and the large size of the tombstones shows that wealthy families wanted to distinguish themselves from others.

In the colonial section distinctions between the rich and poor are evident, but the difference is not as pronounced. Differences can be noted in the size of stones, the existence of a footstone and elaborate carving.

The largest stone, though, is not based on wealth, but on status in the community. It commemorates the death of Reverend Nathanael Hooker who passed away in 1770 at age 32 after serving the Congregational Church for 12 years. His stone is the only tablestone in the burial ground, but is in a sad state of disrepair. The four pedestals collapsed a long time ago and are stored at the Noah Webster House. The bottom slab and the top of the table can be viewed in the burial ground. The full inscription on the “table” details Hooker’s contributions to the town and champions his role as the best-educated man in the community. He was known as a brilliant man who ministered well. His role as doctor, however, did not serve him well in that he treated himself with mercury, leading to his demise. This tablestone can be found in the center of the east side of the burial ground.

Men’s graves tended to be larger than women’s and more elaborate. Samuel Stanley, who died at age 38 in 1787, had both a headstone and a footstone and his stone is much larger than that of his wife, Anna, who died at age 33 in 1780. Anna had no footstone. This reflected women’s partnership with men, for they are buried next to one another, but also represents the patriarchal society in which they lived.

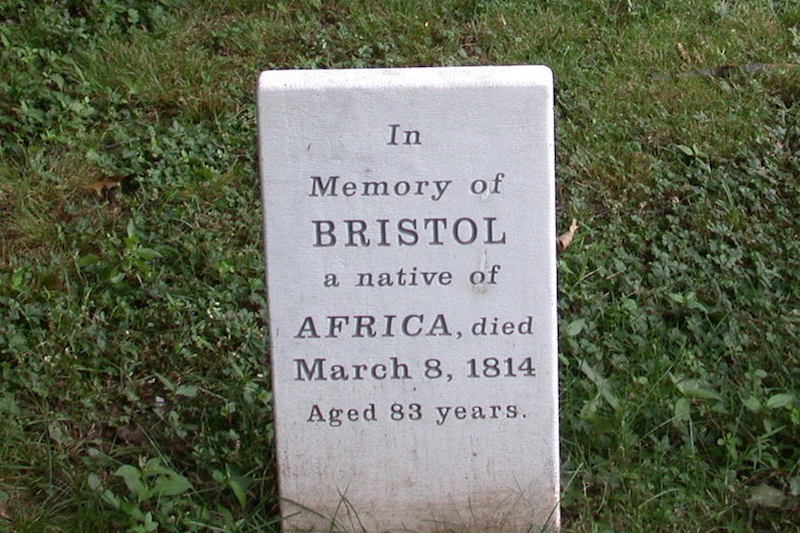

Only one African American’s grave is marked in the burial ground, though I believe more are buried there. A man by the name of Bristol has a gravestone standing alone in the northwest corner. His stone reads, “Bristol, An African, Died 1814.” It is a simple but powerful remembrance of a man who bought his freedom from Thomas Hart Hooker in 1776 and who gained a reputation for his agricultural knowledge in his adult life. West Division farmers often consulted with him. However, he could not be buried “among” them, and he was only given one name on his tombstone. Like his membership in the church, his location was separate in the burial ground.

A walk in the Old Burying Yard brings you back to another place and time. But it also jars you with the underside of life in the 20th century. The gravestones are in a bad state of disrepair. Trees and weeds compromise the stones. Lichens grow. And the writing on many of the stones is no longer readable. Vandalism from 1990 when 34 stones were damaged has still not been repaired. Can we afford to leave this window on the past in such disrepair? What does this tell us about our connection with those who came before us?

Mary Merrell

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, March 2002

When Jacob Merrell died from an accidental fall on his pitchfork in 1771, his wife Mary Merrell was left widowed. She never remarried, and lived in the West Division until her death in 1792. Surviving as a widow at that time in history was challenging, as it was seemingly impossible to live as a single person in an 18th century household. Mary stands out because she seemed to do quite well as a widow, probably through the support of her seven children.

How did Mary do more than just survive for the 21 years after her husband died?

The Merrells lived on the Farmington Road, now known as New Britain Avenue on their farm where Wolcott Park is located today. Samuel and Jonathan Skinner, Joseph Skinner, Allyn Seymour, and Charles Seymour were her neighbors. At the top of the hill, on the corner of New Britain Avenue and South Main Street stood a one-room schoolhouse for the south end of town.

Mary grew up in Wintonbury Parish (now Bloomfield), and married Jacob Merrell in the 1750s. Jacob was 41 at the time of their first child’s birth. When Jacob died at age 57, he and Mary had four girls and three boys who ranged in age from 16 to 4. Mary bore children in 1755, 1757, 1758, 1760, 1762, 1766 and 1767. Thus was the life of a farming woman.

According to Blackstone’s four-volume legal code written in 1765, married women were literally “covered” by their husband’s authority. Her “very being or legal existence,” he wrote was “consolidated into that of her husband; under whose wing, protection and cover she performs everything.” As a married woman, Mary Merrell could not own or buy property in her own name, enter a contract or write a will. Once she was widowed, she gained some of these rights back.

We can get an idea of how Mary lived by comparing the probate record of Jacob Merrell when he died in 1771 with Mary’s inventory when she died in 1792.

Upon a husband’s death, wives received one-third of their husband’s wealth, called the “dower’s share.” The most valuable “movables” Mary received were a feather bed bolster, a year old heifer, curtains, a blanket, and six silver teaspoons. Each of these items was worth more than a case with drawer (a blanket chest with one drawer). She also acquired a bed, two pillows and two blankets. For her third of the farm, she got a one-year-old heifer.

She also received one-third of the real estate of land and house. The probate records described specifically what parts of the house legally belonged to her. Along with getting the South Lower Room, she also got the “liberty to use the fire place in the North Room for washing and baking and to pass and repass thro’ the entry North Room and Kitchen to the well.” She also got the west end of the barn and the liberty to use the barn floor for carting in hay and threshing and feeding the cattle.

Her oldest son Jacob, who was 13 at the time, owned the other two-thirds of the estate. What would it have been like for a grown woman to have to depend so heavily on her 13-year-old son?

Mary’s inventory on her death 21 years later provides a window on how she survived for those years without a husband. She kept many of the movable goods she received in 1771 and she added a large number of goods showing that, though she may not have prospered, her standard of living probably did not decline noticeably.

By the time of her death, when she was in her late 50s, she had items that reflected economic production, furniture and clothing, and items that went beyond the necessities.

There was clearly economic production in her house. Mary had a churn, Dutch wheel, and two hetchels for preparing flax to spin into linen. She had a few hogsheads and two meat barrels in which to store her food. She had one pig, two cows, and one steer. She had a right to the horse house and she owned 36 acres of land in her own right. She also had two hives of bees, which aside from her animals and land, were her most valuable property. Perhaps she got these hives during the Revolutionary War when West Division families chose to stop importing British traded sugar.

She had about the same amount of furniture, and had added blankets, quilts, another bed and several sheets. She had many more kitchen tools including a porridge pot, teapot, large basin, brass kettle, large iron kettle and a washtub.

Her ownership of a clock, two “best” tablecloths, five teaspoons, five napkins, and two pictures show the growing gentility of the age. The standard of living for all New Englanders improved over these twenty years, and Mary’s ability to buy or produce these items shows that she was able to improve her standard of living.

Her children were in their 20s and 30s by time she died. Some of them must have stayed to help her or lived nearby.

Mary had enough money to pay her funeral expenses which included, in order of value, a gravestone, money for the distributors, two quarts of gin, money for the surveyor, money for the advertisements, money for “time and trouble,” one quart of rum, and a horse and wagon.

Widowed farm women had to live with others to survive, and Mary Merrell had her children. She could continue to run the household and, in Mary’s case, her honey might have given her some extra buying power. Women could choose not to remarry, but my guess is that Mary’s 21 years of widowhood would have been remarkable in small town New England.

Old Lights and New Lights

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, October 2003

In 1977, local historian Elizabeth Hathaway wrote a “Chronology of some of the events that might have been discussed by West Division families during Noah Webster’s youth.” In this four page chronology of the years 1757 to 1774, she notes two particular events about choosing a new minister and buying and settling land in the Susquehanna which tie the reader to colonial and international affairs, illustrating how learning the history of our town, then the West Division, can teach about national and international issues.

Choosing a new minister was part of a web of larger events. The issues of fate, salvation, the role of the sermon, the role of emotions and good works were all part of the decision about who to choose as the next pastor. In 1759, Benjamin Colton, the first minister in the West Division, died. He served the town for 46 years and baptized Noah Webster, Jr. Colton trained to be a Congregational minister at Yale, and so was ordained by other ministers, not by bishops. Pastors from surrounding towns, including the First Church in Hartford, ordained him.

Colton held the beliefs of an Old Light minister, a man who supported the Puritan ideals of the colony’s founders. Old Lights had softened some of the strict rules of the church and the Halfway Covenant allowed more members into the church. The New Lights challenged the established Old Light clerical leadership who were trained at Yale. They emerged from the First Great Awakening in the 1740s. New Lights were considered more evangelical, and the sermon, which could move congregants emotionally, was more important than the reasoned sermons of the learned Old Light ministers. New Light ministers were not college educated, but were known for their ability to preach.

The Hartford ministry liked the revivals at first. They felt they breathed new life into their congregations. Itinerant preachers like George Whitfield – an outsider, without a Yale education - preached in the area. As the New Lights gained followers, the Old Lights condemned them. Local Puritan ministers refused to approve New Lights for ordination.

The Old Lights, like Benjamin Colton, supported the Presbyterian associations that were set up by the Saybrook Platform in 1708 which centralized the choosing of ministers to make sure that they were products of Yale and the traditional preaching of the Puritans.

New Lights wanted each church to have congregational independence. They accused Old Lights of believing that people could control their salvation contrary to the belief that their fate was established at birth. New Lights said that the Old Lights examined people’s lives, not their hearts. New Lights opposed the rational, more intellectual teachings of Old Lights. These New Light evangelical ministers allowed congregants into their churches without being baptized and attacked Old Light ministers for being spiritually dead.

There must have been some discussion of these issues in the West Division upon Colton’s death in 1759. In that same year, there was an attempt to oust the Old Lights from control of the General Assembly which met in both Hartford and New Haven, but it was not successful.

In 1759, the West Division congregation elected Nathanael Hooker, another Yale graduate, thus affirming the Old Light control of their church. But the New Light presence did not disappear. Just seven years later, in 1766, a parish member invited a New Light minister into the group and it was deemed a disorderly thing to do. The influence of the First Great Awakening had West Division residents thinking, but their allegiance remained with the Old Lights.

A second issue which brought world issues to the West Division was Connecticut land claims in what had become Pennsylvania. The Connecticut Charter dating back to the 17th century claimed Connecticut’s land stretched from sea to sea. This led to overlapping claims with William Penn‘s charter, which most people agreed, superseded this charter. But, some people, especially in eastern Connecticut still believed they had jurisdiction over western Pennsylvania. The French also claimed some of this territory.

People in the Connecticut colony started a land bank where people borrowed and deposited money. The deposited money earned interest, and people put up Susquehanna land as collateral for the money they borrowed. The land bank invested in the Susquehanna land company. Speculators in eastern Connecticut had done so for years.

Noah Webster, Sr. subscribed to this land bank in 1754; he owned land there that would be bought by a settler. This land was disputed during the French and Indian War which endured from 1754 to 1761. When the war ended and the threat of the French and the Indians dissipated, settlement began in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania.

However, the Proclamation of 1763, part of the French and Indian War peace treaty, banned settlement in the Susquehanna land. Webster’s investment seemed to have lost its value. But, in 1769, Connecticut residents, in direct opposition to both Parliament and the Pennsylvania colony, once again settled in the Susquehanna.

This settlement stirred up old tensions over Connecticut’s charter. Opponents of settlement, who tended to be Old Lights, felt settlement jeopardized Connecticut’s charter. They feared that this charter, which allowed for an elected Governor, not an appointed one by the Crown, would be in jeopardy if the settlers persisted. Connecticut was the only colony which did not have a Royal Governor, and the Old Light leaders believed Connecticut should lay low and not draw attention from Parliament in any way.

After Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765, New Lights took the principled stand of proclaiming the tax as evil. They questioned the Parliament’s ability to lay an internal tax and used this issue to unseat the Old Light Governor Thomas Fitch. Fitch had written a pamphlet on the issue, but he had not opposed the Stamp Act strongly enough. William Pitkin, a New Light, won the election and took control.

Webster, Sr., aligned with the New Lights, while he lived in an Old Light town. Certainly there would have been those here who would have discouraged the speculation in Pennsylvania land. We can only guess whether Webster was making a political statement along with trying to make some money. We do know from Hathaway that Webster, Sr. was elected a grand jury man in 1760, and a selectman in 1768 and 1769, and from 1772 to 1774 he was elected Treasurer of the Ecclesiastical Society when Nathan Perkins, a Princeton graduate, became minister, upon Hooker’s death.

In the 1760s, tensions abounded in the West Division. These religious, economic, and political tensions were often tied to national and international events. The beauty of local history is that it provides specific evidence, familiar to us, that helps shed light on these broader events and ideas. The local and national events can each gain deeper meaning when we can make those connections.

Here Lies the Story of Elisha Seymour

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, November 2011

Elisha Seymour died at age 32 in October 20, 1776 of “the putrid fever” while serving in the West Division ’s militia to fight the British in the Revolutionary War.

He left an inventory of his “reale and personal estate” which allows us a window into the world of revolutionary America. By carefully reading Seymour’s inventory, one can discover what he did for a living and something about his position in the community.

Noah Webster House researchers found Seymour’s inventory in the Probate Records Collection at the Connecticut State Library. They searched through the Fourth Congregational Church records to find out how big his family was to try to recreate the texture of his life.

Elisha married Rhoda Sedgwick on June 13, 1762 when he was just 18 years old. Their first son Elisha was baptized just seven months after they married, a sign that premarital sex is not new.

Just 14 months later they had their second son. Rhoda and Elisha went on to have five more children, for a total of six boys — Elisha, Levi, Theron, Herman, Luther and Ambrose — and the last, a girl born in 1773 named Prudence.

When their father died in the war, their children were ages 2 to 13.

Seymour’s fighting in the Revolutionary War may have led to our independence, but what did it mean for Rhoda and her seven children? We don’t know how soon she remarried, but it would have been most difficult for her to survive on her own.

At age 13, it would have been difficult, but possible, for son Elisha to act as head of household.

Seymour’s inventory was used to appraise the total value of his estate so that his debts could be settled and his belongings could be fairly distributed to his heirs. The colonial court appointed appraisers, usually neighbors, to conduct inventories.

For Seymour, Daniel Webster (Noah Webster’s uncle) and Noah Webster Sr. appraised the property. Solomon Ensign and Benjamin Gilbert appraised a few more items that were tacked on to the end of the inventory, completed almost a year after his death on October 16, 1777.

Usually, the wife received one-third of the estate and the sons got the other two-thirds. Seymour’s entire estate was worth 257 pounds, 6 shillings and 10 pence.

He owned land, but probably not enough to be a farmer. He owned a house, three acres of land and a barn worth 140 pounds. This made up about 55 percent of the worth of his estate.

He also owned eight acres of woodland worth 33 pounds, about four pounds per acre. In the 1770s in New England, a middling farmer needed about 50 acres to make a go of it.

Seymour owned a yoke of oxen (10 pounds) and four cows (10 pounds) that provided him with a means for transportation and milk. He owned one draft chain and a narrow axe. He also owned a “chair carriage,” which likely was pulled by his team of oxen.

He owned seven stock sheep and two swine. He had two bushels of flaxseed in his inventory as well. Flax was used to make linen cloth.

Clearly, Seymour did not have enough land to make a living as a farmer. Further down in his inventory, a set of shoemaker tools and a pair of boots is listed. He owned a shoemaker’s candlestick as well. So, he would have had a farm, but would have made a living as a shoemaker.

To process the wool and flax, Seymour owned two wool cards, a great wheel and a Dutch wheel for spinning. Cloth manufacturing was going on in his home, probably by Rhoda and the children.

In the kitchen, his household had a new corn basket and a frying pan. He had three old cider barrels and two hogsheads. He had a pepper mill, an old brass kettle, a box iron and heater, old knives and forks, a shovel and tongs, a pair of hand irons, a great trammel and a small, both installed in the fireplace.

He had two powdering tubs, three bottles, one stone jar, one coffee copper pot, a tea kettle and an iron pot. He had two great platters, five pewter plates, two pewter basins, a pewter teapot, three glasses, a china cup, a warming pan and a punch bowl.

The poor used wooden utensils, so the existence of pewter objects shows that Seymour did have the ability to show signs of gentility. Pewter cost about one-tenth of the price of silver, but still the cost of a dish equaled what a skilled craftsman could earn in a day. More than 300 pounds of pewter were shipped to the American colonies annually in the 1760s.

He also had eight earthen plates made by the local potter. He had a hand-held looking glass. There was a glass decanter and a glass cruet for vinegar. Seymour had an iron kettle and iron shovel for the fire, a pair of flat irons, which may have been manufactured in western Connecticut where an iron foundry was established in the early 1700s, despite British policy that no manufacturing could be done in the colonies.

In colonial homes, rooms had many different functions: Homeowners moved their furniture around daily. The best room where guests visited would also be the parental bedroom. Seymour owned two chairs, two feather beds and a second bedstead. a trundle bed and a bed quilt. He had three pillows and two pillowcases.

He also possessed woolen sheets. These woolen sheets could be a sign that Seymour bought locally woven woolen cloth. Cotton cloth was manufactured at this time in England, but Patriots like Seymour would have chosen not to import such materials during this time period.

He also owned linen sheets. Flax plants were grown right west of Webster ’s house down the hill in what is now Rockledge Golf Course. The two bushels of flax seed in his inventory point to home manufacturing of these sheets.

Before the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, flax literally sustained people in colonial America. It was grown in every colony. It was not only used for its fiber to make cloth. Flax also was used for its linseed oil.

Seymour’s ownership of a tablecloth and curtains were a sign of the increased ability to produce cloth and the sign of a growth in consumerism.

Clothing was a valuable part of anyone’s estate in the late 1700s. Seymour had four coats, four vests, one pair of leather breeches and one pair of knit breeches. He had three pair of stockings, a new checked linen shirt, two plain shirts, a yard and a half of cloth, six pair of trousers, a silk handkerchief, a pair of gloves, a pair of shoes, a pair of shoe buckles and a pair of knee buckles.

He stored his clothing in a chest of drawers and a white chest. Seymour owned a gun and two powder horns. It is notable that he left a gun at home, because he probably had one with him while serving in the militia.

Seymour also owned two Bibles. He had a mariner’s calendar, a book called the Young Man’s Companion and an Old Mariner book. The shoemaker was both literate and religious.

Finally, he had a “note against Joseph Waters” worth 4 pounds 16 pence, 7 shillings. This note made him a lender, not a debtor.

Seymour made a living at one of the most commonly practiced trades in colonial New England. Because it was so easy to set up shop, the competition could be fierce and by the late 18th century, ready-made shoes from England were part of the competition.

With non-importation that came with the American Revolution, this could have helped him financially. Instead, he chose to go off to war.

Perhaps young Elisha had taken up the trade by that time. My guess is that family and maybe even the town had to step in to help Rhoda as she managed her household of eight without her husband.

Textiles in Early West Hartford

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, February 2002

Go see Lucy Young’s tablecloth and towel in the Noah Webster House’s exhibit “Textiles 2001.” The tablecloth is an “M’s and O’s” pattern made of natural linen. It is 23.5 inches wide and uses three panels of cloth. Woven sometime between 1775 and 1820, it has a hand netted fringe similar to fishnet attached on all four sides. Lucy Young signed her name to this tablecloth.

Lucy Young demonstrates her skill weaving natural linen using the “M’s and O’s” pattern. The fringe on the tablecloth denotes a sense of gentility in a growing consumer culture. It also represents women’s role in an economy based on work by both men and women. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

You can also see a towel, known then as a “point twill diamond diaper” with a cotton tab on each end. This, too, was woven between 1775 and 1820 and belonged to Young. These pieces of woven cloth are beautiful, and represent so much of the change and tension of life in a small town in Connecticut at the time of the new nation.

I happened to view these two textiles, among the 30 on display in the exhibit, while I was in the middle of reading Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s new book, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (2001). Ulrich argues that textiles, as much as farming, were the center of the economy of the new republic in New England. When you find out how linen cloth was made, you get an idea of the interdependence of men and women and a feeling of the rising sense of gentility in places where people had been living for almost 100 years.

Ulrich, a Harvard history professor, uses a linen tablecloth from New Hampshire, very similar to Lucy Young’s, as an example of household production. She argues that the edgings, tassels and fringes were a sign of “emerging neoclassicism and the spread of rural refinement.” She spends a chapter showing how this tablecloth reflects New England’s industrial beginnings, not as a radical departure from home production, but as an adaptation to what they already knew. She describes the interdependence of men and women in household production.

When we think about Lucy Young’s tablecloth within Ulrich’s interpretation, it gives us a new window on life in the West Division.

Local historians believe that flax was grown west of the Webster house, in what are now Rockledge Golf Course and the neighborhood that surrounds Duffy School.

Daniel Webster, grandfather to Noah, had a loom in his house. His inventory in 1766 listed one peck of flaxseed worth 1 shilling 3 pence, and 7 pounds of flax worth 6 pence.

Flax was planted in May by farmers who sowed the seed by broadcasting it. The seeds were light, but it was difficult to seed evenly. To plant a half an acre, farmers needed ¾ of a bushel of seed. In June, women often weeded the flax. Three or four days of harvest in late July or early August meant pulling the flax plants up by its roots, being careful not to tangle the stems. New Englanders let the plants grow long enough to produce seeds and the next step was to remove the seeds from the stem to save them for the next planting. Ulrich reports that in one Connecticut town, merchants exported more than 4,000 bushels of flaxseed in one year. West Division farmers probably produced only for local consumption. Daniel Webster’s flax seed was probably from last year’s crop.

The next step was to “ret” the flax to get the hard outer stem off the silky fibers. Interpreters at the Noah Webster house believe that this was done in the brook, which today flows through the golf course and then runs through a pipe under the Conard High School athletic fields. Ulrich believes that many New Englanders retted flax in the fall by placing the flax on the grass where it would soak up the dew, until the outer shell broke down. Whichever method was used, it smelled terrible.

If you go up to the garret in the Noah Webster house you will see the tools used for the rest of the process. A “braking” machine swings a heavy plank onto a small bundle of flax and then a small paddle was used to separate the husk that remained. The short fibers called “tow” fell to the ground. Either women or men could have done this task. The husk was saved as tinder to start a fire; processing flax was often dangerous because of its flammability.

Hetcheling was women’s work and could be dangerous. Hetchels consist of a square of wood with an array of nails through which one draws the flax to prepare it for spinning. The Noah Webster House has three different sizes.

Spinning was a big part of women’s work in the early republic. Women spun alone and they spun in groups. They spun flax and wool. And they spun day after day.