An Independent Town

Democracy in the Mid-19th Century

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, December 2000

What did freedom and independence mean for the new town of West Hartford in its first decade? How did democracy take shape in this town of about 1,200 Americans in the 1850s and 1860s?

Democracy here was contentious and bipartisan. The 153 men who petitioned to the General Assembly for independence in 1854 argued that with a population of more than 1,200 and a Grand List of more than $20,000, it was as large as most of the towns in the state.

The 95 men who presented a petition to the General Assembly opposing independence argued that their business was all transacted in Hartford, the population was not large enough, and the new representatives would increase membership in the already too-large House of Representatives. They thought that their indebtedness for roads and bridges would increase taxes in an independent town.

The General Assembly accepted the petition for independence and those who were opposed were brought into the new government. By looking at the town meeting minutes from 1854 to 1863, one gets an idea that this was a highly participatory democracy.

By 1860, West Hartford had a population of about 1,200 people. Of that, about 600 were men and of the 600, at most half of them were over 21 and eligible to vote. With about 300 eligible voters, at the first Town Meeting in June 1854, the citizens voted 31 men into office. Jobs included selectmen, grand jurors, constables, treasurer, registrar, fence viewers, pound keepers, haywards, and sealer of weights and measures, indicating the agricultural basis of the town. Later on jobs including school visitors and a board of relief were added.

If 31 men out of 300 voters were elected, more than 10% of the voting male population served in elected office, making up almost 3% of the total population. The equivalent today would be 1,800 officeholders in the town for our population of 60,000. Today there are 18 elected town officials (nine on the Town Council, seven on the Board of Education, a Probate Judge, and a Town Clerk).

These first officeholders, elected in May 1854, indicate that the townspeople wanted a bipartisan government. Of the 31 men elected to office, 18 signed the petition for independence, eight signed a petition against, and five did not sign either petition.

The townspeople quickly mended fences and worked shoulder to shoulder. They met at Town Meetings twice a year, usually in March and October. Between 1854 and 1863, they voted on the candidates, the tax rate (anywhere from 5-7% of assessed value of their property), building roads, establishing a second cemetery and attempting to build a Town Hall.

And they argued about all of it. In November 1857, a resolution passed that said no person could speak on one subject more than twice or for more than 10 minutes.

In 1858 as the town tried to separate itself from the power of the Congregational Church, citizens debated who should take care of Goodman Green, property of the Church. At first the town voted to take over care of the green from the church and “a committee would be established to grade, fence in, improve the park near the meeting house.” The motion went on to ask that $20 be set aside to pay for these improvements. Then it was amended to have the town take possession of the land. Then it was amended to table the whole idea. Then it was voted to drop the issue indefinitely. The town also attempted to build a separate meeting room so that town meetings did not have to happen in the church.

The discussions about this issue began in 1858 and finally in 1863 the town purchased the Congregational Church’s vestry building to serve as a Town Hall. At every meeting during this period of time, citizens debated the roads: where to build, how much to pay workers, how much to pay the highway surveyors ($1.25 per day), where the roads would go, and making the highway district the same as the school district.

Collecting taxes must have been troublesome because there was constant mention of how to collect those that were in arrears. The highway surveyors collected the highway taxes separately and citizens were taxed separately for one of the eight school districts in the town.

Newcomers to the town were the beneficiaries of this roadbuilding. The 1850 census showed a considerable number of laborers born in Ireland living in town. Laborers were paid about one dollar per day to work on the roads. The labor of these Irish men, many of whom had families here, was much in demand as the town grew. However, there is no evidence that any of these men served in any elected town office during this period of time.

Decisions about education also led to protracted discussions. Education was an important foundation of the town and town government. Each of the eight school districts had their one-room schoolhouse. Each hired its own teacher and collected their own school tax. In 1859, the district known as “the commons” (presently the area around Charter Oak School) wanted to join together with the district to its east, in Hartford. The resolution to accomplish this was voted and re-voted over a two-year period until the cross-district school became a reality.

Citizens fought over who was in each district and whether one district got more funds than another. In 1860, the town voted to collect taxes as a town and divide them among the districts to equalize the spending. It was not until the 1890s that consolidated schools were built.

The town also closely monitored its care of the poor. When it separated from Hartford, one of the stipulations of being an independent town was taking responsibility for the poor. West Hartford chose to do this by providing for the poor citizens in their place of residence. The town provided firewood, food, medical care and clothing for those in need. But the town was also circumspect about its money. It paid medical bills of $1.25 to Dr. Wells and Dr. Brace, but then made a resolution that the town would not make another payment of that amount of money unless it was approved by the selectmen ahead of time. A resolution passed in October 1856 said that a particular woman, Sarah Cadwell, could receive no more aid until it was proven she was a pauper of the town.

It was rare for events outside town to impinge on the town meeting, but the Civil War certainly did. At the March 1861 meeting, the town voted to pay a bounty of $30 for every man who enlisted. It voted to pay five dollars in money or goods and services to any resident family whose son or husband went to war.

West Hartford’s fledgling democracy in the 1850s and 1860s deliberated and exemplified the idea of civic engagement for those landholding men eligible to participate. That these meetings were contentious and bipartisan is a tribute to its citizens and the system itself.

When Abraham Lincoln Came to Hartford

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, December 2008. Thanks to Eugene Leach, “Glimpses of Lincoln’s Brilliance,” Hog River Journal, Fall 2005.

March 5, 1860. I can imagine a 16-year-old William H. Hall making his way to Hartford in an open carriage.

He could have joined a “larger infusion of young men than was usually the case in antebellum political assemblies,” as the New York Times described the crowd, to hear Abraham Lincoln give a speech. Lincoln had not yet been nominated for president; that would come two months later on May 16 in Chicago, but he was looking for a national audience. I want to believe that Hall would have been there based on his political interests.

His town of West Hartford had been an independent town for less than six year. The population was about 1,300 people, perhaps 200 families. During the 1850s, the new Republican Party appealed to local voters emphasizing higher education, banking, railroads, industry and cities, and free homesteads to farmers.

The Republican Party started as a revolt against the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed settlers to vote on whether there would be slavery in their territories. The Republican Party pledged to stop the spread of slavery.

In 1858, 136 men voted in the local election, about 85 voting Republican and about 50 voting Democrat. (See Nelson Burr’s From Colonial Parish to Modern Suburb, p. 46.) It is likely that the native born were Republicans and the more recent immigrants including the Irish, German, French, and Swedish listed in the 1850 census were more likely to be Democrats.

Hartford, a city of some 29,000 people, was a solidly Democratic town. This might have encouraged the interest in West Hartford’s independence movement in 1854. The first officers in the new town and delegates to the General Assembly were Republicans.

On Lincoln’s swing through the northeast, he claimed to be visiting his son Robert at Phillips Academy. But by February, Lincoln clearly had an interest in the presidency.

He made a series of speeches in New York, New Hampshire and Connecticut to make himself known nationally, as he was seen as a sectional candidate from the northwest. His most famous speeches were the one given at Cooper Union in New York City and the one given in New Haven, the day after his Hartford speech.

Still, the Hartford speech is worth noting. In it Lincoln established himself as a strong opponent of the extension of slavery and slavery itself, even as the Republicans were trying to moderate their stances to show that they were not abolitionists, but instead merely opposed to the extension of slavery.

He spoke inside a packed Hartford City Hall on that Monday in March. According to the Hartford Courant, he was “greeted with applause which was almost deafening.” Lincoln used the image of a snake to represent slavery, as he established the Republican focus on banning the extension of slavery. For instance, Lincoln argued:

…out in the street, or in the field, or on the prairie I find a rattlesnake. I take a stake and kill him. Everybody would applaud the act and say I did right. But suppose the snake was in a bed where the children were sleeping.

Would I do right to strike him there? I might hurt the children or I might not kill, but only arouse and exasperate the snake, and he might bite the children.

Thus, by meddling with him here, I would do more hurt than good.

Slavery is like this. We dare not strike at it where it is. The manner in which our Constitution is framed constrains us from making war upon it where it already exists.

The question that we now have to deal with is shall we be acting right to take this snake and carry it to a bed where there are children? The Republican party insists on keeping it out of the bed.

His statement clearly spoke to his audience on the dangers of slavery’s spread. With the focus on the extension of slavery, there are some who argue that it was hard to tell whether Lincoln was against slavery when he took office a year later.

He claimed that when the Union entered the Civil War, it was to keep the Union together, not to abolish slavery. Some say his stance was not clear that he was opposed to the institution of slavery until he issued the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862. However, at Hartford’s City Hall on March 5, Lincoln declared:

…the free states carry on their government on the principle of equality of men. We think slavery is morally wrong and a direct violation of that principle. We all think it wrong. It is clearly proved, I think, by natural theology, apart from revelation.

Every man, black, white, or yellow, has a mouth to be fed, and two hands with which to feed it, and bread should be allowed to go to that mouth without controversy. Slavery is wrong in its effect upon white people and free labor. It is the only thing that threatens the Union.

This clear declaration denouncing slavery on intellectual and economic grounds pushes the Republican feelings that they had to tread lightly on the topic of slavery or a Republican would not be elected president. Lincoln was clear in his declaration against slavery.

The most interesting aspect of his speech was how he tried to find common ground with southerners, highlighting how important economics were in their political decisions. Unlike William Seward, the frontrunner for the nomination, Lincoln did not demonize the southerners. In fact, he found what the two sections had in common:

One sixth, and a little more, of the population of the United States are slaves, looked upon as property, as nothing but property.

The cash value of these slaves, at a moderate estimate, is $2,000,000,000. This amount of property value has a vast influence on the minds of its owners, very naturally.

The same amount of property would have an equal influence upon us if owned in the North. Human nature is the same; people at the South are the same as those at the North, barring the difference in circumstances.

Public opinion is founded, to a great extent, on a property basis.

What lessens the value of property is opposed, what enhances its value is favored.

Public opinion at the South regards slaves as property and insists upon treating them like other property.

Lincoln’s claim that “people at the South are the same as those at the North” would have been anathema to abolitionists, and even to Seward, who claimed that those in the South were greedy and amoral, while those in the North were idealistic and righteous.

This position was one that echoed through Lincoln’s presidency, including one of his most famous lines found in his second inaugural.

With malice towards none; with charity for all…to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow, and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Here Lincoln does not distinguish between Union and Confederate people. If William Hall did indeed hear him, he probably would have then proceeded with the crowds led by the Hartford Corner Band, which led Lincoln to the home of his host, Mayor Allyn. He also might have been interested in Lincoln’s meeting with Gideon Welles of Glastonbury at a local Hartford bookstore after his speech.

The next year, Welles was appointed Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy.

The Town’s Role in the Civil War

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, August 2005

When the Union went to war with the Confederacy in April 1861, West Hartford had been an independent town for only seven years. Its population stood at almost 1,300. Thirteen men, 1% of the population from West Hartford died in the Civil War. At war’s end, West Hartford had sent 117 men to serve, almost 10% of the population and about half of the male population of military age. The sheer number of men and the newness of the government may have led to fewer records being kept. But, the tally of West Hartford men who served and died in the Civil War (1861-5) probably tells less about West Hartford than any other war.

Incentives in the form of bounties led men to move from town to town. West Hartford’s quota of 44 men was oversubscribed by 83 recruits. Many of the 117 were not West Hartford residents. It is more difficult to verify that those who died actually lived in West Hartford.

West Hartford men who served were lured by federal, state and local bonuses. Connecticut offered each man $140 for enlisting while they received $27 from the federal government. In May 1861 just one month after the opening salvo at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, West Hartford residents voted at town meeting to borrow $3,000 for war bounties and for the families of soldiers. Male citizens voted for every inhabitant who enlisted in military service for three years to get $30 or its equivalent in equipment and clothing. Families of those who enlisted were paid a monthly amount of up to $5 and $2 for every child under age 12. At first, the town paid this money to all those who enlisted from West Hartford, but within six months, rescinded the amount to those who it was determined did not live in West Hartford.

There was much incentive for men to become “bounty jumpers.” They enlisted in one town, got the money, and then deserted. Then they showed up in a second town. Wealthy men were able to “buy” a replacement for $300. Of 20 deserters from West Hartford, it is thought that many were never residents here.

The Union’s many advantages made Union recruits believe the war would end quickly. Those who mustered first, signed up for 90 days. There were heavy casualties. The first six West Hartford men who died in 1862 averaged just four months in the army.

The Civil War was the last war in which soldiers for the same regiment were mustered from the same town. For instance, at the 1862 Battle of Antietam, the 16th Connecticut Regiment had nine West Hartford men. At this crucial battle in Maryland, the Union Army stopped General Robert E. Lee’s first invasion of the North in September 1862. On the bloodiest battle day, September 17th 1862, more than 23,000 men were killed, wounded, and missing. West Hartford’s Edward Deming died on that day. At Antietam, three West Hartford men were killed, four were disabled and two survived to fight another day. Charles Sternberg and Arthur Talcott died of wounds within three months of the battle. West Hartford was thought to have suffered the most of any town its size from this particular battle.

In the 1860s, the majority of West Hartford’s population consisted of white Congregationalist farm families. But the town’s population was changing. The 1850 census shows a growing presence of Irish and German immigrants and African Americans continued to live and work here. These demographic patterns were reflected in the Civil War dead and the enlistees.

Charles Sternberg, who died at Antietam, was one of four German immigrant brothers who fought in the war. Their father Charles emigrated from Germany in 1854 as a result of the 1848 Revolution. Charles established a farm at the corner of Sedgwick and Mountain Road. One brother William was imprisoned at Andersonville and survived.

The 24th Connecticut Regiment included three Irish companies one of which came from Hartford and West Hartford. West Hartford’s John McCarty, who had been a musician in the Regiment, was sent to the front lines and killed at the siege at Port Hudson, Louisiana in the second assault on June 14, 1863. Port Hudson was a pivotal battle for control of the Mississippi. The siege began on May 23, 1863 and lasted for 48 days. About 30,000 Union troops fought 6,800 Confederates. On the morning of May 27, and again on June 14, the Union army launched assaults against the earthworks protecting Port Hudson. McCarty sacrificed his life in the second assault. Finally, the Confederacy surrendered on July 9th, seven weeks later.

Once the men got to battle, there were many deserters. In light of the conditions in the Union Army, it is not surprising that desertion was so rampant. It is thought that over 200,000 deserted over the course of the war. The daily hardships of war, lack of weapons, and forced marches which sometimes made straggling a necessity for less vigorous men, caused some to desert. West Hartford’s John Hall mustered and served but died by a military execution for deserting. The military used men like Hall as examples to try to reduce the number of deserters.

West Hartford’s Thomas Wells wrote a letter to his family in 1862 claiming to march 20 miles per day, sometimes in the pouring rain, with only a cup of coffee as nourishment.1 J.G. Butler wrote that the army made it hard for soldiers to keep a high morale. Butler marched 300 miles in seven days.2

The horrors of the Civil War were made real to West Hartford residents through the first war photographs, letters, and returning men. In R. H. Morse’s letter to West Hartford’s Mrs. Elizabeth Sisson, 23 July 1863, he wrote “Only three short weeks before, our regt. left Hartford with over one thousand brave men ready to strike a blow for liberty and restore our glorious union once more… Only those who have seen it or have been engaged can tell one half the scenes of horror or carnage of the battlefield. Imagination fails to conceive the one half of it.”3

West Hartford men’s Civil War experiences show their willingness to join for a common cause and of a town to support them. Not everyone enlisted for the same reasons and their fighting situations varied greatly. Some could well articulate the purposes of war and some fought for bounties. The local history becomes more meaningful and complex when intertwined with state and federal policies and world immigration patterns.

West Hartford’s First Foray with Regionalism

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, December 2006

An 1869 map of West Hartford shows an aqueduct running from a small reservoir #1 down Farmington Avenue into West Hartford center then on to Hartford. This first reservoir, authorized by the Hartford Water Board in 1866, flooded 32 acres of West Hartford land. But West Hartford residents could not drink the water from the sheet iron pipes coated with cement. It bypassed the town to serve the city of Hartford, which by 1860 had 30,000 inhabitants, to West Hartford’s 1,200.

The aqueduct was the beginning of a regional solution to a regional need. In 1857, the Water Board in Hartford realized the city needed to provide more water to its inhabitants. Its population had more than doubled since 1850, and there was not enough potable water in the Hog or Connecticut Rivers. A report by the Water Commission in 1860 recommended that the supply of water should come from the hills west of the city and make its way by gravity, through pipes, to Hartford. Trout Brook seemed to be the perfect source for this water. Hartford’s 1856 petition to the General Assembly to get water from West Hartford was finally granted. The Water Board acquired the pasture land and woodland on the north side of Farmington Avenue that we now know as the MDC reservoir.

There was some resistance in West Hartford to the reservoir system. Residents of the newly independent town of West Hartford (1854) did not take well to Hartford damming the brook which also brought their 1200 residents not only clean water, but a source of power for its grist and saw mills. An organized protest of West Hartford mill owners and citizens with water rights, however, was not successful. Resident William H. Seymour and 400 West Hartford citizens showed their support for the project by presenting a petition to support the reservoir project.

In 1866, Hartford’s City Engineer began construction of the 53 foot high dam which held back 145 million gallons of water, 260 feet above the Connecticut River. The first water reached Hartford in January 1867. Many West Hartford residents living along Farmington Avenue felt that they should be able to drink the reservoir water as the pipe went right by their houses. In a legal proceeding, West Hartford argued that because the water came from West Hartford territory they should get it for free. West Hartford citizens felt that the possession of the water outweighed the cost of the pipes. The courts decided that they could access the water, but had to pay the same rate as the people in Hartford.

Just eight months after the dam was completed, torrential September rains broke a portion of the dam, and the wall of water flooded across Mountain Road, on to Fern and North Main streets, carrying away three bridges. The water deposited stones and gravel on farm land and destroyed fences. The City of Hartford paid $12,000 in damages to the town for the damaged roads and bridges and over $17,000 to individual farmers and mill owners for damages. It took almost three years to rebuild the dam. They opened reservoir No. 2 in 1868, No. 3 in 1875, No. 4 in 1880, and No. 5 in 1884, and No. 6 in 1896.

As soon as the Farmington Avenue electric trolley was built past the reservoir in 1894, the reservoir became an even bigger destination for walking, picnicking and “pleasure riding.” By 1930, the reservoir area comprised 1,625 acres of land or about three square miles of West Hartford’s 22 square miles.

In 1929, the regional governing body, the Metropolitan District Commission was established with seven member towns including Hartford, Windsor, Wethersfield, Newington, Bloomfield, East Hartford, and Rocky Hill. By the 20th century, as West Hartford developed, the cleanest water was found even farther west in Barkhamsted and in New Hartford. By 1930 as is true of today, our water no longer came from the West Hartford reservoirs, but residents wanted to be sure the three square miles remained as open space for recreation in the town.

In the twentieth century this land has been used as a treatment facility for the water from Barkhamsted. West Hartford’s facility near Reservoir No. 1 and Bloomfield’s facility near Reservoir No. 6 treat an average of 55 million gallons of water daily. The facilities treat all of the drinking water provided to MDC customers. Today portions of Glastonbury, East Granby, South Windsor, Farmington and Portland use MDC water but are not members of the Commission. About 400,000 people get water from the MDC in 2006.

West Hartford did not become a voting member of the MDC until the last quarter of the 20th century. In 1981, Republican Mayor Chuck Matties encouraged the town to join the Metropolitan District Commission. With rising rates in the early 1980s, Matties felt that West Hartford should have a say on the Board. This was not necessarily a popular stance to take because people in town often worried about being involved in a regional solution. But Matties led the charge to join the other seven towns in the District. With the Town Council split 5-4, and his Republican caucus divided on the issue, he and two other Republicans joined two Democratic council members to join the MDC Board. A follow-up referendum passed overwhelmingly by the voters.

In November 2006, voters got a chance to vote on an $800 million improvement to the water system. This referendum was prompted by federal and state mandated regulations to address sewer overflows where water gets into pipes carrying sewage. Damages from the 2005 rains that caused sewer overflows in Elmwood have finally been settled.

But now the Commission has to take on this regional maze of pipes which carry both clean water and sewage and the cost is high. The 15 year project has an estimated price tag of $1.6 million, with the first phase estimated at $800,000. While many of us believe water should be free, the cost of maintaining pipes today is just as much of an issue as in the 1860s when West Hartford residents were told that water is no longer free!

Elmwood’s Industries

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, July 2001

West Hartford has the reputation of being an upscale inner ring suburb. Many of its residents live here and work in Hartford. But, since the 19th century, West Hartford has had an industrial base that differentiates it from suburbs that are solely residential. Those businesses and their workers add to the stability of our town.

The first Industrial Revolution in the United States began in the 1820s with canals, textile mills, and the growth of the market economy. West Hartford’s residents bought ready-made cloth and products that came from around the world.

Until the 1850s, the main industries in the West Division were grist mills, distilleries and blacksmith shops. The individually owned mills were tied to the only source of power — water — until the mid-19th century.

West Hartford’s largest early industry was the Goodwin Pottery. The Goodwins began their business in 1798, before the railroad came. The West Division had excellent clay deposits and the company produced earthenware jars and containers sold throughout New England. The jugs the Goodwins produced also served the town’s local distilleries. Fires plagued the pottery works, but after the second one in 1867, the Goodwin sons bought land south of New Britain Avenue where the present Abbott Ball Company stands, just west of the railroad tracks of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railway Station that had been built in 1839.

By the end of the 19th century, the Goodwin Brothers diversified their line of earthenware to offer terracotta objects with ornate designs for outdoor and indoor decoration. They also made fine china. The market for these goods encompassed the span of the railroads, so became nationwide.

The Goodwins developed a large market for their products and soon their industrial site took up ten acres. By the beginning of the 20th century, they employed over 75 workers. Their workers may have included some of the immigrants who had moved to town. By the 1860s, a sizable number of Irish and Germans lived here.

With the railroad, the Goodwins hired salesmen to replace their traveling peddlers. These men sold the Goodwin’s wares all over the eastern United States.

In 1908, a fire destroyed the wood frame factory. By then, H. Burdette Goodwin, who was in his 60s, decided not to rebuild the factory because of competition from other container makers.

The Providence and Fishkill Railroad (later the New York, New Haven and Hartford), whose tracks ran through the southeast section of town, changed the nature of the small farm town, by the 1850s. Industry grew up around this new transportation route and allowed for increased trade to distant points.

After the Civil War, the second Industrial Revolution based on heavy industry like steel grew in the northeast. Hartford became the machine tool capital of the country, and West Hartford’s industries were a result of this industry. With the factories came immigrants. By the late 1800s, Scandinavians and Italians moved to town.

In the 1870s, Hartford boomed economically; it was dubbed the wealthiest city in America. Industries in Hartford grew and prospered, built to a certain degree on the profits of Colt’s Manufacturing. By the turn of the century, as the insurance companies began to grow, there was little industrial land left for expansion. West Hartford had land available

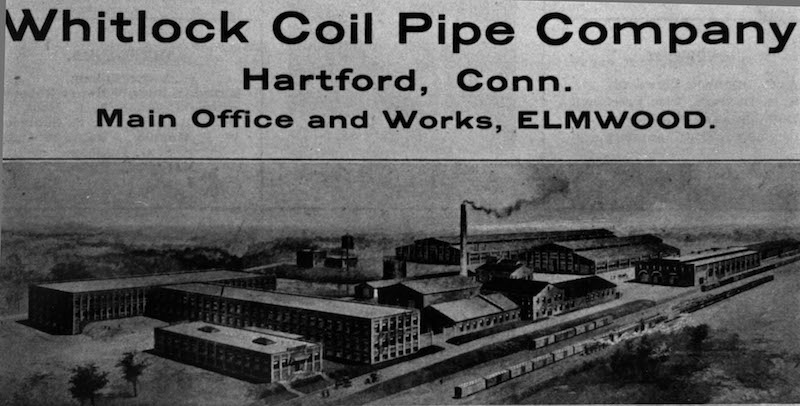

In 1891, Whitlock Coil Pipe Company moved to South Street along the railroad tracks. In 1913, the New Departure Company moved to West Hartford from Bristol. The company made push-button doorbells and ball bearings for the growing automobile industry in Hartford.

Whitlock Coil & Pipe Company moved to West Hartford in 1892 and was West Hartford’s first big factory. They built their new factory south of New Britain Avenue and just east of the railroad line. Founded by 35 West Hartford men, Whitlock made products that transferred heat through bent pipe and tubing. They specialized in a feed water heater that connected to steam boilers. President Charles Edward Beach from 1898 into the 1920s also owned Vine Hill Farm, a dairy farm, much of which is now Beachland Park. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

Like many industries of its day, New Departure built something of a company town by buying a large tract of land between Woodlawn Street and Newington Road. The company divided it into 100 lots and sold them to employees at low prices. This allowed workers to live close to their jobs. These industrial workers who owned their own homes had a real stake in the town and added to the stability of the neighborhoods in the southeastern section of town.

During World War I, employment at New Departure grew from 200 to 1,200 in a matter of a year. The contracts for war materiel added workers and profits. In 1910, West Hartford’s population stood at about 4,800, and grew to 8,000 by 1920.

In 1912, Abbott Ball Company moved to the old Goodwin Pottery site from Hartford. Abbott began producing steel balls and became one of the largest producers of deep-hardened and tempered carbon steel ball bearings. Many of these ball bearings were made for the auto industry in Hartford.

In 1954, the founding family still owned Abbott Ball and employed 105 workers. They produced ball bearings for cars, conveyors, and lazy susans. In 2001, Abbott Ball employed a few more workers than 50 years before and was the 14th largest employer in West Hartford.

In 1919, Spencer Turbine moved to West Hartford. Wiremold arrived in 1929 and continues its manufacturing after being bought out by LeGrand in 2000. It continues to be one of the town’s largest taxpayers. In 1939, Pratt & Whitney Machine Tool factory moved to the site of the old Charter Oak Race Track. This was the largest industrial site in West Hartford. By the late 1950s, Chandler Evans, Colt’s, and Pratt & Whitney Machine Tool shared the site. In 1954, the three companies employed 5,000 people.

Since 1970, industrial production in West Hartford has slowed and commercial and retail sales have grown. But the blue-collar workers in Elmwood’s factories played an important role in the town’s growth. While the owners, financiers, and middle class commuters often have a high profile in town, these industrial workers also help define our suburb.

The Story of Vanderbilt Hill

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, March 2004

In a recent class, I asked my students if they had ambition. Do you expect, I asked, to live in a house larger than that of your parents? At least three-quarters of the students answered yes. I wondered at the pressure that put on them, and when the size of houses and rooms in houses would ever level off. Then I remembered the Vanderbilt Mansion.

In the mid 1870s, Cornelius Vanderbilt decided that his son, Cornelius, Jr. should have a mansion and that its location should be West Hartford. The mansion was to be built on a 75 acre farm at the peak of Farmington Avenue, across from Whiting Lane. Vanderbilt selected and bought this site in the late 1850s after he had surveyed prospects for the New Haven Railroad and the Providence & Fishkill railroad having routes through West Hartford.

Mark Twain called Hartford the richest city in the world, and New York City was building its reputation as the center of commerce and culture in the United States. West Hartford was but a farm town. The population in 1880 stood at just over 1,800, and the town had been independent from Hartford for only 25 years. No doubt the town was beginning to change with farmers specializing in dairy, and an increase in the number of immigrants, but wealth even on the scale of the most scorned Vanderbilt son hadn’t really been seen before in the town.

Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877) first made his money when he monopolized ferry service and then shipping on the Hudson River. By the mid-19th century, he invested in the luxury liner business and then by 1857 in railroads, eventually taking control of the New York and Harlem Railroad, and the New York Central. He built Grand Central Terminal in New York City and employed thousands of men during the Depression which began in 1873.

Vanderbilt had two sons, and eight daughters. Young Cornelius never lived up to his father’s expectations and was sent off to live in a modest farmhouse on what is now known as West Hill, the same hill on which his mansion was built. His father bought the 75 acres in 1857 from the Hamilton family. Cornelius, Jr. hated every minute he was away from New York City. While living in West Hartford, young Cornelius went into debt. When his father died in 1877, he thought his money problems were solved. However, Vanderbilt left his son William $95 million dollars, his eight daughters split four million dollars, and Cornelius received just $12,000 a year.

Cornelius, Jr. tried to use the money to break his father’s will. This gave him some ability to borrow money to build what he called his “dream house” on Vanderbilt Acres. He borrowed half the price of the $60,000 house, a fortune at the time, for this area, but only a small amount compared to his father’s and brother’s mansions in New York City.

Cornelius hired architect John C. Meade to design a 27 room house on Farmington Avenue. Meade designed a four story tower mansion with a view of Hartford and the valley to the west. The mansion’s cupola rose five stories high. The central hall was wide enough for a horse and buggy to turn around in. The mansion had a veranda on three sides. The brownstone wall and entrance are the only things left from the house, setting it off from Farmington Avenue

But, Cornelius had no luck breaking the will, and thus was stripped of his West Hartford house and land. Meanwhile, sympathetic friends bought it and sold it back to him for $1. However, Cornelius never lived in the house. He committed suicide in 1882. His desire to “live like a Vanderbilt” never happened.

The house was auctioned off to a real estate speculator and stood empty for six years, while a caretaker kept it up.

Ira Dimock, a rich Hartford silk manufacturer and inventor bought it in 1888 and lived there. In May 1917, his wife died in the house and he died a week later at age 90. In the midst of World War I, no one felt capable of taking care of the house, and it was torn down in 1918.

Ira Dimock, a silk manufacturer, owned and lived in the Vanderbilt mansion from 1888 to 1917. His son Irving Dimock died in the Spanish American War of typhoid fever in a camp training to go fight. Another son, Stanley Dimock teamed up with Horace Grant to tear down the family mansion in 1918 and establish the West Hill neighborhood with 25 homes. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

Dimock’s son Stanley Dimock and Horace Grant, a Hartford manufacturer, developed the Vanderbilt Hill area after the mansion was torn down. The houses Dimock built were smaller than the house he had grown up in. The two men made sure that the 25 homes built were all single family with garages. The developers approved each architect who designed the houses and made sure that each one cost at least $10,000. The development became the first to put electric lines underground. The first house, completed in 1920, stood on the site of the Vanderbilt Mansion.

Both Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jr. and Stanley Dimock built and lived in homes that were smaller than those of their parents. Cornelius would say that his son lacked ambition and his alcoholism sank him into depression. Dimock, on the other hand, chose to make more of the land on which he had grown up by subdividing the land and making a handsome profit. Since 1988, West Hill has been denoted an historic district, representing a new style 1920s suburban neighborhood.

The Vanderbilt Mansion was the first of several mansions in town in the 1870s and 1880s. The first wave of suburbanization was not the middle class, but it was the upper class who moved here first. The Russell Mansion, at the corner of Prospect and Cone Street, built in 1874 was four stories. It too has been demolished. The Home of Yung Wing on the corner of Prospect and Fern was demolished as well. The Judd Mansion on Highland still stands, now surrounded by the Hughes Convalescent home. It wasn’t until the 1890s, when the electric trolley came through that developers began to build middle class housing. The ambitions of the wealthy in the 1870s and 1880s could not be sustained by the next generation as witnessed by the number of these mansions that were demolished.

Who was William A. Burr?

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, June 2009

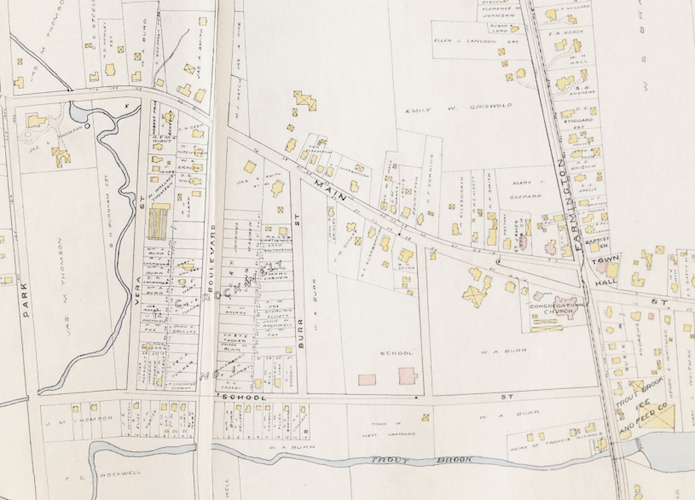

W.A. Burr’s name is prominent in the 1896 and 1909 insurance atlas maps of West Hartford’s town center. He owned the land east of South Main Street to Trout Brook along Farmington Avenue. The land surrounding the First Church was bounded by present-day South Main, Burr Street and Raymond Road, and goes east as far as Trout Brook.

Surprisingly, Burr is not mentioned in any of the histories written about this town. Yet he clearly had a role in its development from rural town to modem suburb. He was a landowner and an entrepreneur.

Burr was born in Hartford where his father, Allen Burr and his grandfather, Thomas Burr, lived before him. Thomas ran the only general store in Hartford on North Main Street, then called Burr Street, near the head of Trumbull Street. William moved to West Hartford with his family when he was five, probably before this town was separate from Hartford.

William A. Burr was at first a farmer. In October 1873, a news article proclaimed that Burr could “boast one of the best orchards in the state. Mr. Burr’s orchard has produced 150 bushels of apples and his pear trees have been unusually prolific of choice varieties.” In the 1870s he took his produce and his animals to the Connecticut State Fair near the race track on New Park Avenue.

By 1875, Burr had established a hardware store and carriage shop. An 1875 news short claimed that “Mr. W.A. Burr of West Hartford has the agency for the sale of the Tompkins County Self-Tilting Wheel Rake said to be the best wheel rake, seeder and plaster sower combined that there is in the world.”

This “Carriage Repository and Hardware Store” stood at the present site of the Noah Webster Library. There were two buildings in his operation in 1896 and 1909. Burr’s success with the sale of new farm machinery was a sign of the increasing industrialization of farming and of his role as entrepreneur.

In Burr’s role as businessman and real estate owner, he amassed wealth. He owned a summer vacation home in Branford at Short Beach and a winter home in Ormond, Fla., just north of Daytona Beach. A Hartford Courant article in October 1910 described William A. Burr buying land for a winter residence in Ormond, Fla. The paper claimed it was a time of “remarkable growth of resorts in Florida.”

In 1913, the pastor of the Congregational Church, the Rev. Thomas M. Hodgdon, expressed an interest in building a new church and a new parsonage for the growing church. He cited the congestion in the center and the increasing value of the present site for business purposes. Burr delivered.

In 1914, according to the Hartford Courant, William A. Burr, most likely a member of the church, donated a strip of land to the First Church of Christ in the center of town. The land was 19 feet on Farmington Avenue by 15 feet deep and ran on the east side of the church. This strip of land straightened the line of the church’s property and allowed the church to provide easy access to the sheds in the back of the church where people stabled their horses. It also allowed them to level the rear lawn and beautify the property.

On this 1909 insurance map, note William A. Burr’s land on the corner of Farmington Avenue and Main Street, and on Main and what became Burr Street. Burr owned the Carriage Repository & Hardware Store just south of the Congregational Church and Parish. Sandwiched between was the Masonic Hall. Another piece of his property came to the town to build William Hall High School in 1924. Burr died in 1923. Source: Atlas of the City of Hartford, and the Town of West Hartford, Connecticut: L.J. Richards & Company, Springfield, Massachusetts, 1909, Plate 23.

The article claimed that Burr was thinking about running a street along the eastern boundary of the church property from Farmington Avenue to Seyms Street (now Memorial Drive), giving the church a corner on which they could possibly build a chapel.

In that same year, the Barker-Tanner Hardware Company bought Burr’s retail business. This was the same year the A.B. Judd Company was incorporated as a druggist and it purchased the building it occupied on the comer of Farmington Avenue and South Main Street.

In 1923, right after Burr died, his estate was valued at $112,681 ($1.2 million in 2009 dollars). The real estate on Farmington Avenue was more than half of the total of the estate. He had half a block of frontage on Farmington Avenue just when the Center started to become a retail center. He also owned land on Vera Street to the southeast of the center and two parcels of land on South Main Street, one worth $6,500 and one worth $7,300. He owned four parcels of land along Farmington Avenue.

In May 1924, the First Congregational Church bought a tract of land from Burr’s estate south of its property for $59,000. The new tract was between South Main, Seyms Street and a proposed street running from Raymond Road to Seyms (the current Isham Road). This land helped the First Church survive during the Great Depression in the 1930s, as it was sold to the town to build the Town Hall and library. These building projects, along with other development in the Center, helped define the burgeoning suburb.

South Main Street from Farmington Avenue to Burr Street was the scene of much building activity by 1924. The population had grown to 9,000 and residents wanted to be able to take care of their needs without going in to Hartford.

The Masonic Temple was under construction on the west side of South Main Street. Hall High School was in mid-construction. The town was prepared to move two houses from the Hall High site to make way for the school. The West Hartford Trust Company site was being readied for the first bank in town.

Burr’s land sale, after his death, provided an important opening for economic growth as well as the placement of public buildings in the town center. Burr Street stands as a reminder of a man who successfully navigated the change from farm town to suburb through his real estate and business acumen.

Who was Burdett Loomis?

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, March 2008

Farmington Avenue is once again getting a makeover, and it seems like a good time to look back at the work of Burdett Loomis who led improvements on that Avenue in the 1870s, over 130 years ago. Burdett Loomis, (1838-1919) was a businessman and entrepreneur whose vision helped transform West Hartford from a farm town to suburb.

Loomis was an inventor, patent holder, and manufacturer of gas plant machinery and a citizen who “planned ahead for Hartford and West Hartford” according to a 1912 Hartford Courant news article. The 1912 article was prompted during improvements-in-progress on Farmington Avenue that year. Prospect and Farmington were each a standard three rods (48 feet) across and Loomis wanted to widen them to 75 feet.

By 1873, Loomis owned the land bounded by Farmington Avenue, Prospect, Fern and Vanderbilt Hill, now West Hill. Loomis was married in 1859 at age 21 and moved to Hartford in 1871. He first lived on Wethersfield Avenue in Hartford and in 1873, built what became known as the Russell Mansion on Prospect Avenue. This house had ornamental woodwork and a stately tower. It stood on the west side of Prospect near Cone Street, close to where the Bristow Middle School is today. It has since been torn down. Loomis seems to have lost his first fortune as a result of the panic of 1873, so was forced to sell the mansion, and in 1878, he moved north to 837 Prospect Avenue just south of Elizabeth Park, on the West Hartford side to a more modest home built in 1845.

When Loomis first moved to Prospect, he believed that Farmington Avenue would be “one of the finest thoroughfares out of Hartford” into West Hartford, Farmington and further west. Loomis also believed that Prospect Avenue should be wider and when Loomis asked Hartford to share in widening the street from 48 to 75 feet, the city refused to take land from the Hartford side even though no houses had been built there. Loomis reduced the grade of the avenue for about 1/3 of a mile to one inch in every 100 feet. He cut down trees and then planted a row of trees between Farmington and Fern. He spent $1,000 of his own money to widen Farmington Avenue. As the town widened the street, the “Great Panic” –- probably of 1873 –- took over, and he lost most of his fortune.

Loomis’ businesses helped West Hartford grow through ingenuity and public utility and transportation systems. Loomis was a part owner of the trolley company. He was instrumental in getting the horse car line extended to West Hartford Center in 1889. Loomis also had a hand in the building of the water pipe system from the reservoir. It first opened in 1867 before he was here, but he worked on getting the pipes laid under the road and accessible to West Hartford citizens.

In 1881, at age 43, he organized the Steam Heating Company of Hartford. He soon found problems with the steam heat in that so much was lost in its transmission. He decided to substitute cheap natural gas to heat and invented cheaper methods to make gas, which was soon used for gas engines. From 1886 to 1889, he built the first gas plant that produced gas from coal, wood or lignite and delivered it to its domestic users through pipes laid underground over long distances. His company laid gas lines on the frontier. By 1899, Loomis headed the Loomis Gas Machinery Company in Hartford. His company laid iron pipes for gas and water, both important pieces in building the infrastructure of towns and cities.

In 1882, he organized the first Electric Lighting Company in Connecticut. By 1912 he and his son, Burdett Loomis, Jr., served as directors of the Northern Connecticut Light and Power Company. His son was also treasurer of the company.

Throughout these years as a developer, Loomis made and lost several fortunes, according to family legend. Probably Loomis’ biggest gamble, and his best fun came when he helped establish Charter Oak Race Track in 1873. Loomis promoted and developed the race track at Flatbush and Oakwood Avenues. In 1876, he planted the elms in the front of the park on New Park Avenue and had the avenue widened. The park became one of the finest trotting courses in the country. Loomis saw his first trotting race on a half mile track on Hartford’s Albany Avenue in 1861. When he relocated to the city, he believed Hartford should have one of the best courses in the country. He chose the site, organized the association, superintended the building of the track, planted the trees and gave the grounds a park-like appearance. Loomis had backing from Charles M. Pond and Governor Morgan Bulkeley. The track drew all the leading harness horses and their drivers. He was Secretary of the Charter Oak Association in 1880. Bets ranged from $100 to $20,000.

In 1882, Loomis decided he wanted a special event in Hartford, and he drafted conditions for a $10,000 purse over Labor Day Weekend, one of the largest in the nation. When Loomis proposed the large purse, people thought he would lose money, but Governor Bulkeley, the treasurer of the association guaranteed the race. It made money that year and every year after. That race continued into the 1920s, even after Loomis’s death in 1919.

Loomis was one of the seven men who “labored zealously to establish and maintain the “Grand Circuit” of harness racing. This circuit gave light harness racing the prestige that it has maintained to date. Charter Oak Park was on the Grand Circuit until 1925.

Burdett Loomis, according to Caroline Church, was one of the men who helped turn West Hartford from a small farming village to a suburb over 100 years ago. In her senior college thesis, which brought Loomis to my attention, she focuses on the role of public improvements, particularly the West Hartford Reservoir system in defining the changing nature of West Hartford from 1870 to 1910.

He was certainly a man of his times –- a businessman, an entrepreneur, and a man who wanted to give back to his community. His maxim throughout his life, still rings true today: “to do something for the world and the community, regardless of whether or not [he] was going to reap the benefits derived therefrom.” Something that distinguishes West Hartford from other towns is that there are so many in West Hartford who continue to abide by this maxim.

About this book

Copyright © 2018 by Tracey M. Wilson. Life in West Hartford is freely available online at http://LifeInWestHartford.org and distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Readers may share the work for non-commercial use, by including a source credit to the author.

Print copies of this book are available for sale from the publisher, the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society, in West Hartford, Connecticut. Proceeds of sales benefit the Society http://noahwebsterhouse.org.

George Wells to Mrs. Elizabeth Sisson, 2 June 1862, Butler Bassette Collection, Noah Webster House archives.↩︎

J.G. Butler to Mrs. Elizabeth Sisson, 13 January 1863, Butler Bassette Collection.↩︎

R.H. Morse to Mrs. Elizabeth Sisson, 23 July 1863, Butler Bassette Collection. Morse mustered on July 25 1862 as part of the 16th Connecticut Regiment.↩︎