Development and Reform

Evolution of the Town Manager Form of Government

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, June 2006

West Hartford’s town meeting served as a check on local governmental power from 1854 to 1919. For 65 years, the town meeting election of three selectmen and appointments to numerous boards seemed to serve the town well. But, as the population tripled from about 3,000 in 1900 to about 9,000 in 1920, the town meeting became unwieldy. There were no auditoriums big enough for the meetings and with the added services provided by the town, government had grown into something more than volunteers could handle.

By 1917, the state passed an ordinance allowing the town of West Hartford to move to a town manager system of government which seemed like it would be more responsive to the town’s needs. In 1919, the town adopted the council-manager form of government which put the power to run the town in a Town Manager, and the power to make policy in the hands of a 15 member Town Council. West Hartford was the first town in Connecticut to adopt this form of government.

The Town Council hired Benjamin Miller as our first Town Manager in 1919. He grew up in Avon, and took a two year business course at the New Britain Seminary. He served in Avon as selectman, founder of the Avon Library, chair of the school board, Judge of Probate and Democratic Representative to the General Assembly. During World War I, he was chair of the Draft Board for the Farmington Valley including West Hartford. When he became Town Manager, the three main issues facing the town were construction, maintaining and paving roads, zoning and running and building schools. The first charter called for the Town Council to appoint the Town Manager, Town Treasurer, Tax Collector, Controller, Town Engineer, Building Inspector, Town Auditors and Constables. They also had the power to appoint commissions and commissioners.

Under Miller, in 1923, the town established the first comprehensive zoning ordinance to regulate land use in Connecticut and a Town Planning and Zoning Commission. The town hired its first paid police chief in 1923. In 1925, candidates for Town Council ran as members of a party, rather than as non-partisan candidates. The grand list grew from $19 million to $65 million. In 1929, the first woman, Grace Honiss, a vice president of the League of Women Voters became the first woman elected to the Town Council. And the town built Plant Junior High (1922), Talcott Junior High (1922), Hall High (1924), Beach Park School (1926), Smith School (1926), Elmwood School (1928), added onto Charter Oak School (1930), and Sedgwick School (1931).

But all was not well with Miller’s administration. He was a Democrat and Republicans dominated the Council throughout the 1920s. It was unclear where power lay –- with the Town Manager or with Commissioners. Commissioners felt they had the right to appoint people to paid positions like Town Engineer and Building Inspector, and seemed to have used these positions as patronage. The Town Manager believed he should have the power to appoint the paid positions by merit, but this power seemed to have been taken away from him by the early 1930s. He resigned in 1933, under stress.

When Miller left in 1933, he sued the town for back pay from his original contract made in 1919. He started at $4,000 per year and his salary increased to $4,800. However, once the depression hit, Miller’s pay was cut from a high of $4,800 to $4,400, ostensibly due to the financial problems associated with the Depression. But, Miller also left amid tension over loss of power in his job and the rise in the power of the town commissions headed by Town Council Members. He also left as the Great Depression deepened and the town pushed to have its employees take pay cuts.

Within 15 years, the government charter already needed reform. By 1930, the population rose to almost 25,000 and the system of government had not fulfilled its original promise. In February, 1934, the Town Council hired a professor from Bowdoin College to study the way the town government worked, with an eye on proposing a more “businesslike plan of government.” The first report to the Town Council on the new plan for government claimed that by 1933, the town manager position had sunk to “innocuous desuetude,” meaning “disuse.” Apparently, Miller had fallen out of favor and spent little time at his job as his power got siphoned away by Town Council members, some of whom served as Commissioners.

By September 1933, the Town Engineer who had been appointed by the Republican controlled Engineering Commission, Rodney Loomis, was running the town as the Town Manager. He retained both posts until he was finally made the official Town Manager. New Town Manager Rodney Loomis’ salary had soared to $7,500 by 1935.

Loomis took much of the power away from the commissions by also serving as Director of Public Works, Director of the Police and Fire departments and the head of the Tax Department. In 1934, the 10 Republicans and 5 Democrats on the council agreed to this shift in power, believing Loomis had the best interests of the town in mind. Republican Max L. Goldenthal was President of the Council for the three years he served. While Loomis served, he convinced the Council to take advantage of building money provided through the federal government’s Work Progress Administration as part of the New Deal. The town built a town hall and library, financed about 45% by the federal government, on land that the First Church sold to the town to stay afloat during the Depression. The Democrats aligned themselves with the West Hartford Taxpayers Association, which submitted an alternative budget each year.

The new 1935 charter reduced the Council to seven members, five elected by district and two at large. The charter established the position of Council President which in 1947 became “mayor.” The council seemed willing to give up the day to day running of the town to Loomis where the previous councils were not so willing with Miller.

Loomis was known for being “gruff and business-like” and he ran the town efficiently. He stayed in his position for 22 years, until 1955, one year longer than Barry Feldman who just resigned after 21 years on the job.

In 2006, West Hartford is only on its ninth town manager in 87 years. A council that agrees to be a policy making body, not an administrative body, and a non-partisan manager seem to be a successful combination. At this rate, new Town Manager Jim Francis should take us through to 2020!

The Story of Susie Butler Andrews

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, December 2004

You’ll find the name Susie B. Andrews as the owner of land in West Hartford center in the 1909 Atlas of the City of Hartford and Town of West Hartford and the 1923 Sanborn Maps. Often women whose names appeared as property owners were actually holding land that their husbands controlled. But, in Andrews’ case, the Historical and Architectural Resource Survey of the Town of West Hartford (1982) by the Connecticut Historic Preservation Office tells us more. Susie B. Andrews, the study claims, “did a great deal to shape early West Hartford Center, building and managing commercial and residential properties.” How did she help shape the center as it moved from residential to commercial?

According to her grandson, C. Allan Borchert, Susie grew up on the northeast corner of Main Street and Farmington Avenue. Her house was torn down to build the West Hartford Trust Company (now Bank of America). When she married Myron Andrews, a banker at the Colonial Bank in Hartford, she moved to 12 North Main Street. She was a shrewd business woman, who, Borchert recalled, was a tough negotiator. He remembered his grandfather in the early 1930s bemoaning her death in 1930 while he worked on his dairy farm. “If only Susie were here,” his grandfather said.

The first residential development in the town center came when Frederick Rockwell bought and subdivided the King family farmland southeast of the center in 1896. Rockwell laid out parcels on Burr Street and had a grand plan for Boulevard which came to fruition between Memorial Drive and South Main Street. The houses in this subdivision were built between 1900 and the mid 1920s.

The second residential development, northwest of the center was named West Hartford Heights. Developers subdivided this land around 1900, and the lots sold, but houses were not built until after 1914 when amenities like paved streets, electricity, and water were available. Susie Andrews laid out Dale Road in 1912 and subdivided the property.

The colonial revival house, built in 1912, was moved from Farmington Avenue and Dale Street to 75 Brace Road in the 1930s to make room for commercial development. It was sold in 1970 by Butler Realty and is now a commercial property. Source: Town of West Hartford, CT Vision Government Solutions, parcel photos.

The development of West Hartford Center and the suburbanization of the town coincided with the improvement of transportation to West Hartford. In 1889, horse railway tracks were laid down Farmington Avenue and by 1894, the trolley was electrified. Those who worked in downtown Hartford had a regular, dependable transportation to and from Hartford, making the farm town more desirable as a residence.

Susie B. Andrews had designs on the center. When the population grew from about 3,000 in 1900 to 33,000 by 1940, the retail needs of the town grew as well. Andrews owned land on the north side of Farmington Avenue, west of Main Street and on North Main Street. Even before West Hartford’s zoning laws went into effect, Andrews knew that it was a good idea to separate residential and commercial.

One of Andrews’ residential development properties still stands at 9 Dale Road. This was one of the first houses built on Dale Street and is a beauty salon today. She also rehabilitated the building at 10 Dale Road which was probably an original barn to her childhood home on Farmington Avenue.

To make way for the commercial development, Andrews moved several houses from Farmington Avenue to Whitman Street. The house at 30-32 Whitman Avenue was moved in 1912 when Andrews laid out Dale Road. Frederick Brace’s house originally stood on Farmington Avenue on the east side of the present Dale Road. Around 1850, he set up the first omnibus route between West Hartford and Hartford allowing town residents to commute to Hartford. It operated until the horse railway took over in 1889. This building is thought to have been the Old Academy Building on South Main Street until about 1840 when it was moved to Brace’s property on Farmington Avenue and then moved again to Whitman Avenue.

Susie Andrews moved the colonial revival house built in 1912 which now stands on 75 Brace Road. Most houses along Brace were not built for at least another 10 years when amenities like piped water became available. This house was moved to its location from the corner of Farmington and Dale Street in the 1930s to make room for a commercial building. Myron and Susie Andrews’ son M. Morris Andrews built, owned and lived in this house which was just north of Farmington Avenue and Main Street. This house is identical to the one at 1022 Farmington Avenue.

It seemed that Susie got the area ready for commercial development. But the Depression hit and then she died in 1930 of tuberculosis. At that time, her business became the Andrews Corporation with each of her four children owning an equal share. Borchert remembers the family having lots of investments in land and property, but having very little money. When Borchert’s father died in the early 1930s, he and his mother and sister moved in with his grandfather at 10 North Main. He remembers his grandfather owning a dairy farm which he sold to A.C. Peterson’s farm in Bloomfield in the early 1930s. When his grandfather died, his mother took in boarders to survive.

The commercial building at 984-992 Farmington Avenue (In 2004, housing Chico’s, the Elbow Room, and eight other stores) was built in 1935 by the Andrews Corporation, inheritors of the property of Susie B. Andrews. The commercial buildings like these with storefronts for about ten shops were just starting to come into existence and were just beginning to be known as malls.

The 10-12 North Main Street building, now housing Sally and Bob’s, and the YMCA offices, was built in 1938 and was one of the first large office and commercial buildings in the center. It has details from the Colonial Revival style of architecture, and in that way, matches what was then the West Hartford Bank & Trust building from 1926 and the government buildings including the Noah Webster Library, the Town Hall and Hall High School. It was probably built by Susie and Myron Andrew’s son Morris. This building was built on the site of Susie B. and Morris Andrews’ residence. By this time, Borchert and his mother had moved to another one of the residential properties the family owned, first at 44 Whitman Avenue and then at 32 Grennan Road

The commercial building at 994-1000 Farmington Avenue, built in 1938, was also part of the Andrews retail empire. The Butler Building, named after Susie’s family name (the B stands for Butler) was built on the site of Susie Butler’s childhood home. This commercial building, influenced by the Colonial revival style, has much more architectural detail than the one to its east. Susie’s son Morris probably built the Butler Building as well.

Susie B. Andrews was indeed a businesswoman. According to her grandson, she was also a woman of many talents. She was an excellent artist, painting scenes from her travels to Maine, Bermuda and some from the local scenery. She never sold any of her artwork, but each of her children has many of her paintings,

It is surprising that there was so much development, both residential and commercial, in West Hartford in the 1930s, during the Great Depression. Susie Andrews was instrumental in setting the path for this development. Andrews’ management of land in the first three decades of the 20th century helped to shape both residential and commercial development in the center. These commercial buildings have stood the test of time. Andrews’ attempt to separate commercial and residential properties has held to a great extent as neighbors fight the encroachment of businesses in their neighborhoods. Ironically, Dale Road, Susie’s first real residential neighborhood is almost all commercial today.

A Trip Back in Time to Westmoor Farm

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, January 2006

In 1925, Major A. Raymond Ellis bought 46 acres of land from Frank R. Scott on Flagg Road. He remodeled the barn, house and cottage to accommodate his pack of hounds to lead fox hunts at what he named Westmoor Farm. I usually think of West Hartford in 1930 as a developed suburb, but with a population of about 25,000, the town still retained some of its rural character.

The new suburban residential development was predominantly on the east side along Farmington Avenue near Hartford and along North and South Main near the center. West of Main Street from Albany Avenue to New Britain Avenue still remained pasture and cropland.

The land that the Major bought was originally the property of one of the earliest settlers in town, Thomas Merrill. Born in 1714, Merrill sold the farmland to Abijah Flagg in 1786. The land remained in the Flagg family for about 140 years; the last Flagg to own the property, Willis operated a dairy farm with 30 cows until about 1915. He grew vegetables as well and sold them at a stand he owned in nearby Bishop’s Corner. In 1922 he sold the land to Frank Scott and in 1925 Raymond Ellis bought the property.

Ellis was an architect by profession. He moved to the United States from Nova Scotia in the late 1890s and then moved to Hartford in 1908 after finishing architectural school at MIT. When he bought Flagg’s land and buildings he remodeled them to accommodate riding horses as well as his pack of dogs. Ellis served in the cavalry in World War I. He helped with the reconstruction work in France in 1918 and 1919, using his skills as an architect.

In 1922, just before he bought Westmoor, Ellis was named architectural editor of Woman’s Home Companion magazine. By 1929, over 650 houses of Ellis’ design had been built, in part because of his connection to the magazine. He designed the Park River Bridge, the main building of the Hartford Hospital, the Connecticut Institute for the Blind, and the Isolation Hospital at the McCook Memorial Hospital in Hartford.

At Westmoor, Major Ellis built a riding and jumping course. He also created what he named the “Westmoor Farms Polo Club” in a cleared field on his property. Those who had played polo at the Hartford Golf Club when it was in Hartford had been looking for a place to play since the Club moved to West Hartford around the turn of the century.

Ellis developed a fox hunt team and fox hunt. To lead a fox hunt, one needs open fields, water, and pastures for galloping horses that follow the pack of hounds. He had a pack of dogs trained and run by a man he hired. The fox hunts at Westmoor were done by “drag”: a set fox skin was dragged cross-country to leave a scent trail for the hounds. His hunt was cited in a book by A. Henry Higginson and in an English book called Bailey’s Hunting Directory from 1926 to 1930.

Ellis held two horse shows on his property to entertain those in the neighborhood and make them more friendly to the idea of the hunt. The drag hounds went out three days a week from the middle of March to the middle of May and from the middle of September until snow and ice made the area unrideable. At that time, there were only a few neighbors to win over.

Charles Allen Hunter (1874-1961) bought the land from Hartford Connecticut Trust in 1939 after the bank foreclosed on Ellis in the depths of the Depression. Hunter began to use it for a summer home starting in 1939, the year of his retirement. Hunter had been Vice President at Connecticut Bank and Trust when he retired after 45 years at age 65.

Hunter hired a German immigrant horseman named William Wouters. Wouters first worked at the Westmoor Farms Polo Club owned by architect and retired cavalry officer Major Ellis. Wouters transported horses for club members and saved enough money to buy a horse and wagon to carry building materials. In the early 1920s, Wouters opened his own boarding stables on Albany Avenue at Bishops Corner. When Hunter moved out to Westmoor in 1939, he convinced Wouters to come back to keep his business and take care of Hunter’s horses. Wouters expanded his business to board race horses from Narragansett, RI and Lincoln and Suffolk Downs in Boston. He exercised the animals at Westmoor before racing season began again in the spring.

From 1939 to the late 1960s, Wouters ran his business of breaking horses from Hunter’s stables in return for taking care of Mr. Hunter’s gelding. Wouters lived in a two bedroom apartment above the tack room in the stables. In 1984, at age 91, Wouters still lived in the stable. Wouters took care of the horses of students attending Ethel Walker School and jeweler Bill Savitt, who liked to ride.

In 1961, Hunter died. In his will, he left 56 acres to the town of West Hartford along with a large house, servants quarters, a large barn, stable, several smaller buildings, pasture, brook and pond. He was married to Leila Clark Hunter who according to his will could continue to use the property until her death. When she died in January 1973, the town had to decide what to do with the property.

By 1973, the neighborhood surrounding Westmoor Farms had changed considerably. Houses on Blue Ridge started to be built in the late 1930s through the 1950s. On Flagg Road, at least ten homes were built between 1956 and 1957. The suburban town had grown to a population of 62,382 by 1960. Neighbors had opinions about what should happen to the property.

In February 1974, the Conservation Commission in West Hartford recommended that eight acres of the land be used for an equestrian center for riding instruction and boarding horses. The indoor equestrian ring was to be about the size of the Veterans Memorial Ice Skating Rink, 85 by 185 feet on the southwest corner of the property out of sight of Flagg Road. They would build six paddocks and add some riding trails with his bequest. This they thought could provide a revenue stream for the town.

Besides the equestrian ring, the town planned to add a parking lot for about 70 cars, picnic facilities near the parking area with playground equipment, public bathrooms, a barnyard zoo, and a boardwalk and wood chip and gravel trails through the Hunter property. Hunter’s estate not only left the land, but also a sizable sum of $2.3 million to be used for maintenance of the park. The town received one-half the income from this trust, of about $130,000 per year.

The reality of 2005 shows us that the park was much less developed in the final analysis. Neighbors on Flagg Road vehemently fought the development, and the park stayed in a fairly natural state. The idea of the equestrian ring, which was truly an extension of what Wouters had been doing for about 30 years lasted but a few months before the neighbors had convinced the town that this was not in their best interests.

Today, the vestiges of horses on the farm are few, but for a developed inner ring suburb, Westmoor Park still gives a sense of those rural days less than a century ago, when most residents were farmers and there was enough open land for a fox hunt.

Read more about the fox hunt in a pamphlet written by Robert Anderson called Westmoor Hunt, 1925-30 found at the Noah Webster House. A folder in the WHPL vertical file on Westmoor Park tells the history of the park in newspaper articles.

The Life and times of Edna Purtell

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, February 2007

I first encountered Edna Purtell while writing my master’s thesis on the Connecticut Woman’s Suffrage Movement. She was known for her abilities as a speaker. In an interview, she claimed that she “never wrote any of her speeches on paper, but I could consistently captivate audiences.” When I wrote last month’s West Hartford Life article on William Purtell, a Republican Senator from West Hartford, I realized that the two were brother and sister and yet they seemed to have diametrically opposed political views.

Edna Purtell (1899-1985) was born on Albany Avenue in Hartford, the daughter of a cigar maker. Her father was a member of Samuel Gomper’s Cigarmakers Union. Her father, apprenticed at the age of nine, became a leader in the Hartford union. In 1911, he fought to allow a black man into the union because he knew that blacks, just like the whites, paid the same 5¢ for a loaf of bread. Purtell’s mother was a cigar stripper who belonged to the union as well.

Edna Purtell graduated from the night high school. She held jobs as a babysitter, clerk at the five and ten, and as a tobacco stripper at Doyle’s Tobacco Shop. At 16, she was elected secretary of the cigar strippers’ union. By age 18 she went to work at Travelers Insurance Company in the filing department. Edna’s brother William was two years older than she. While Edna identified with the working class, her brother became an entrepreneur.

In her spare time, Purtell volunteered in the woman’s suffrage movement, handing out leaflets in downtown Hartford and going door to door to get signatures on petitions. A chance encounter in 1918 in front of the Brown Thomson department store between Purtell and Katharine Hepburn (the actress’s mother), the head of the Connecticut Women’s Party led to Purtell taking the train to Washington to demonstrate. There she was arrested in front of Woodrow Wilson’s White House and fined. Purtell represented working class women, and took the train to D.C. and got arrested four separate times and was finally thrown in jail for six days and there she went on a hunger strike all in the name of woman’s suffrage. She was also arrested for climbing Lafayette’s statue and proclaiming “Lafayette, we are here.” Lafayette, a French general during the American Revolution, was a champion of liberty. The police broke two of Purtell’s fingers snatching her suffrage sash while arresting her.

When she returned to work after protesting, Travelers President Batterson called her down to his office. He said, “You know, Miss Purtell, you’re liked very well here, but we don’t want you to be talking about suffrage and so forth.” She replied, “Mr. Batterson, during work hours I’ll take care of my job. But once I get in that elevator, what I talk about is my business, not yours. And on our coffee break, that’s our coffee break, and I’ll talk about anything I want.” Batterson never said another word to her and Purtell’s characteristic honesty prevailed.

Purtell’s suffragist activity with the Connecticut Woman’s Party was more radical than the work of the Connecticut Woman’s Suffrage Association. When women won suffrage in 1920, the more conservative women from the CWSA formed the League of Women Voters. Instead, Purtell became one of the first members and a leader in the State Federation of Democratic Women’s Clubs. Even into the 1970s, when the League became a more progressive group, she never joined.

Purtell served on many committees and was often the keynote speaker for these groups. In 1924 she supported Progressive Robert LaFollette for President because he supported the initiative, the referendum and the recall. She supported the movement to free Ireland from British rule. In 1928, she helped organize a “Women for Al Smith” committee to support the Democrat running for President. In 1930, Purtell was elected Parliamentarian of the Hartford Women’s Democratic Club. She served on the legislative committee which followed bills in the state legislature. She lobbied for jury service for women, old age pensions, and improving the status of women in factories. In March 1933, at a meeting of the Connecticut Women Democrats, Purtell reported on the conditions of jails for women in Hartford County. She said the cells were unsanitary and the women did not have enough freedom. In 1936, she was an alternate to the national Democratic Convention which nominated FDR for a second term.

Her interests were wide-ranging. In May 1934, Purtell was part of a group which sponsored a symposium on Nazi book burning. She joined the pastor of the Center Church, the head of the Seminary, two rabbis and Annie Fisher, the Superintendent of one of the Hartford school districts, to raise awareness of the public.

While Purtell immersed herself in Democratic politics, her brother opened a factory called Holo-Chrome and by World War II he had bought Billings and Spencer in West Hartford. Then he began to dabble in politics himself. Hartford Courant political writer Jack Zaiman claimed he too, was a great speaker, but his view of the role of government differed from his sister. He thought that social problems should be solved through private initiative first and only then through government action.

His sister may have agreed with him about labor issues for men who tended to have strong unions, but she believed strongly that the government needed to regulate businesses.

After several years at Travelers, Edna Purtell got a job as an investigator for the Connecticut State Labor Department. She gave a speech at a rally to support a state pension plan. In 1936, she exposed a case where a dressmaking shop in a Hartford department store made women work more than a nine hour day. She worked for the department for 14 years and was a pioneer for protective labor legislation, particularly for children employed in the state tobacco fields. She wrote a pamphlet for the Labor Department in the 1940s on children in the tobacco industry. She led the fight to end child labor in Connecticut and in 1946 outlined the problems of child labor in a news article. There was no minimum age for agricultural workers and the children worked as many as ten hours per day.

In 1948, the Connecticut Democratic Women’s Convention asked Purtell to be their keynote speaker. It was thought that she might have a place on the state ticket for elective office. At that time she and the Democratic women called for an end to the regressive sales tax and for a progressive income tax. However, she never ran for political office. Senate nominee Thomas Dodd, a Democrat, named her to head his office on women’s concerns in 1956. In that role, she worked for the man who ran against her brother.

The family gathered to support Edna Purtell when she won an award commemorating her life of public service on behalf of women. Source: Purtell family.

After she retired from the state in 1956, she remained politically active. Governor Dempsey named Purtell to Connecticut’s Permanent Commission on the Status of Women in 1966. When the Equal Rights Amendment was revived in 1970, Purtell was one of the first to testify before the legislature’s Human Rights and Opportunities subcommittee headed by Gloria Shafer (who later became Connecticut’s third female Secretary of State). Purtell defined herself as “an old style militant suffragist” claiming that even after women got the right to vote, they “were still not persons.” In 1975, at age 76, Purtell was still active politically. She published a letter to the editor supporting a state income tax and supporting Homer Babbidge’s run for Governor. At that time she served on the legislative committee of West Hartford’s North End Senior Center, continuing to monitor and lobby for legislative measures.

Purtell lived more than 40 years in West Hartford, well into her 80s. While her brother’s political career took him to Washington, it lasted only six years in the U.S. Senate. Edna continued her role as an activist throughout her life, speaking for the rights of those who had the smallest voice.

Amateur Radio in West Hartford

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, August 2010

Town Councilman Steve Adler and Dr. Rick Liftig are two of the more than 175 ham radio operators who live in West Hartford. In a day of instant communication through the internet and cell phone, these amateur operators seem something of an anomaly. In June 2010, Mayor Scott Slifka presented a proclamation to representatives of the American Radio Relay League (ARRL) in recognition of West Hartford’s tie to the growth and support of this organization as he recognized amateur radio’s deep roots in West Hartford. Their communication system serves as a community service in times of disaster as well as a hobby, which three million people enjoy worldwide.

Different from the telegraph, which sent a Morse Code message by impulses over a wire, amateur radio operators send messages over the air waves. The U.S Government through the Commerce Department began licensing operators in 1912.

Hartford’s Hiram Percy Maxim founded the Amateur Radio Relay League in 1914 when he wanted to send a message from Hartford to Springfield and did not have a strong enough signal to do so. He contacted a relay in Windsor Locks and his Morse Code message made it to its intended receiver. Maxim, who invented the Maxim Silencer for guns (1909), and the car muffler, was a radio enthusiast who helped to develop a network of amateur radio operators. In 1914, he was a member of the Hartford Radio Club, but realized there would be an advantage to a wider network of hams. By September 1914, their network grew to over 230 stations. Just 15 months later, there were 600 stations and the ARRL published its first bulletin QST (meaning Calling all Radio Amateurs) to help coordinate the actions of the operators.

When the United States joined the Great War in 1917, the Department of Commerce sent a letter to all amateurs ordering them off the air. During the war, the ARRL coordinated the recruitment of operators into the armed services where they continued to hone their skills for the public good.

In 1918, at the war’s end, the U.S. Government tried to control the transmission of messages under the Department of the Navy, but the ARRL lobbied Congress to allow individuals to control their transmissions and they quashed several bills in Congress allowing them to do so. The ARRL under Maxim’s watch, provided technical advice and assistance to amateur radio enthusiasts, and regulated them before the Federal Communication Commission was founded in 1934.

With Maxim, the first ARRL headquarters inhabited “a couple of shabby rooms” on Main Street in downtown Hartford. In 1925 the staff of 18 moved to 1711 Park Street. West Hartford’s role really began in 1931, when the ARRL built its headquarters at 38 LaSalle Road, where Coldwell Banker was in 2010. This new location housed the League in a two-story building. They had a $200,000 budget and 28 full time employees.

Many amateur radio geeks moved to town who worked at ARRL headquarters. They found housing in the old Selden Hill farmhouse on top of Buena Vista. Rilla and Henry Selden lived in the house up on the bluff and their seven children had grown and moved away. Mrs. Selden posted a “Rooms for Tourists” sign down on Farmington Avenue near the Reservoir. When two men from the ARRL station looked for a place to live, they found, not only a “home,” but also a great radio location where they could experiment.

Associate Editor Ross Hull, an Australian, and Managing Editor Clark Rodimon of QST were some of the first boarders to move in. Rodimon invented the first two-way five-meter contact between Hartford and Boston –- over 100 miles in 1934 from Selden Hill. Hull was known worldwide for his pioneering work in developing the VHF and UHF spectrum for the 56, 112 and 224 MHz amateur bands. According to Rilla Selden, “they strung up a big contraption among the trees. Then Ross talked to a half a dozen fellows in Boston and none of them would believe he was in Hartford.” Hull had strung a high gain beam array in the trees. The amateur radio operators in Boston spent the next half hour “discussing that bootlegger who claims to be in Hartford.” They could not believe that the signal could be sent 100 miles. Hull proved that radio beams could go beyond the horizon and “bend” to the curvature of the earth.

The various boarders continued to experiment on Selden Hill. They scaled the old slate roof to put up transmission lines and they built sky-wires for fun on a Saturday afternoon. Even in 1944, according to an article “The Legend of Selden Hill,” in QST, remains of these structures still existed.

These amateurs were not just satisfied with experimenting with words over the airwaves. They built radio controlled gliders and airplanes. Selden Hill’s steep slope provided a great spot to use as a launch pad. One of these gliders, with a wingspan of 16 feet is at the ARRL station in Newington today.

In the early 1930s, Ross Hull experimented with television at Selden Hill. He wanted to “reduce to amateur practice” the complicated nature of sending pictures over the airwaves. He tried several television experiments in 1937 that debunked the professional opinions that the maximum range of television transmission was 30 to 40 miles. In fact, he successfully received NBC’s transmissions from the Empire State Building over 100 miles away in 1937. Hull criticized the professional television industry for their commercialism. Because the equipment was so much more expensive, amateurs had more difficulty experimenting. Hull moved to Bolton in 1938 where he accidentally contacted 6,000 volts while working on his experimental television receiver and died.

According to present day amateur radio operator Rick Liftig “Virtually all of our modern communication techniques derived from these experiments.” Almost 70 years later, amateur radio operators continue to help the public by radioing in times of emergency during natural disasters. Their dedication to public service and their dedication to their hobby symbolize the community involvement that continues to make West Hartford such a vibrant town. Perhaps an historical marker on LaSalle would help keep this 20th century history alive!

Dr. Caroline Hamilton

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, August 2012

Recently, the daughter of a good friend left for Thailand for a year’s service. Part adventurer, and part human rights activist, Katherine will be teaching English to Buddhist monks in Chang Mai, Thailand. The rise in interest in human rights issues, student exchanges, and college student travel around the globe, are all part of a 21st century global outlook. This generational shift, however, is far from new. Take a look at Caroline Hamilton.

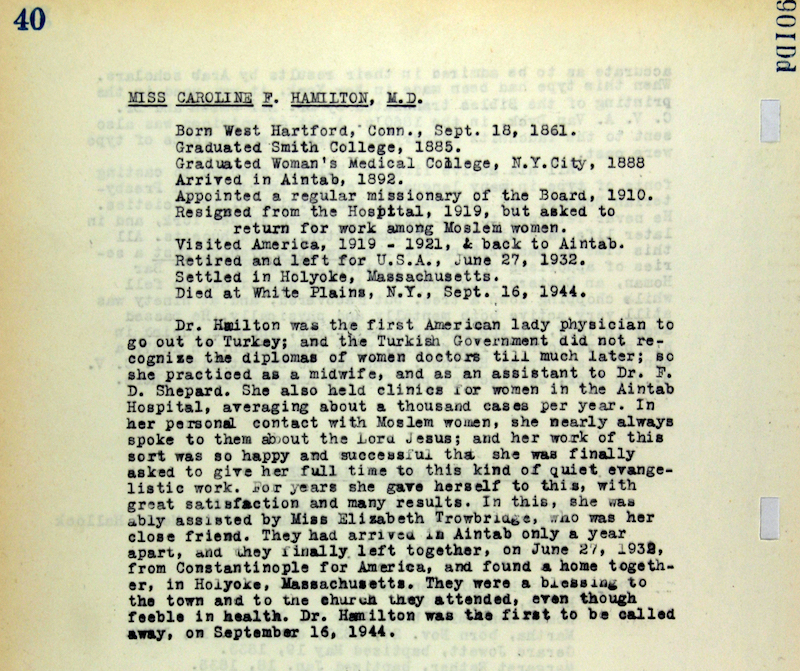

On September 12, 1944, Dr. Caroline Hamilton died at age 83. Her obituary stated that she was a native of West Hartford, a graduate of Smith College, and a graduate of the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. It went on to say that “From 1892 to her retirement in 1932, Dr. Hamilton was medical missionary at the Azariah Smith Memorial Hospital, Aintab, Turkey, in charge of medical services for Moslem women.”

In 1930, William H. Hall, West Hartford’s retired Superintendent of Schools, devoted two pages in his book West Hartford to Dr. Hamilton. In his section entitled Biographical Notes, Hall wrote about four West Hartford families, and 24 individuals, two who were women.

According to Hall, Hamilton was born to Benedict and Electa Hamilton at their home on the south side of Farmington Avenue just east of Trout Brook, on a 70 acre farm near the present site of Kingswood Oxford School. Hamilton went to the West Hartford High School after it was opened in 1872 on North Main Street as the second floor of the Center District School. She went on to graduate from Hartford High School in 1880 and then Smith College in 1885 at age 24.

Hamilton graduated from the New York Women’s Medical College (1863-1918) in 1888. She enrolled in the school when the founder Dr. Clemence S. Lozier was still running the school. Founded in 1863 with seven women, by 1888, 219 women doctors moved into practices from Maine to California. She interned at the hospital for a year, and then got involved in “college settlement work” as a physician, just at the time that Jane Addams and Lillian Wald established Settlement Houses in Chicago and New York City. Wald and other settlement workers tried to ensure that all members of society, including women and children, immigrants and the poor, and people of all ethnicities and religious groups could realize the promise of American ideals of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Hamilton also found time to teach in the Medical College where she got her degree and was a resident physician at the New York Infant Asylum which provided care for abandoned children. The Asylum also provided obstetrical care for unwed or indigent women.

She did more graduate study in New York and in 1892, at age 31, the American Board of Missions appointed her to the hospital in Aintab, Turkey where she worked from 1892 to 1932. A Hartford Courant article from September 19, 1893 quoted an article in Harper’s Bazaar saying that the Ottoman Sultan had granted permission ”for a woman physician to engage in her profession within his domain.” Caroline Hamilton was sent at the expense of a “Boston lady” and she set up a hospital for women and children in Aintab.

A memorial record for Hamilton from the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in Aintab, Turkey tells of her work for 40 years (1892 - 1932). Hamilton saw over 1000 patients per year, focusing on women’s health. The memorial tells that she was aided by Elizabeth Trowbridge, her close friend who lived with her for over 39 years in Turkey, and then they “found a home together” in Holyoke, MA, when they returned. Source: Amerikan Bord Heyeti (American Board), Istanbul, “Memorial records for Caroline F. Hamilton.”

Hamilton’s work took her beyond the walls of the hospital in Aintab to help heal the sick and needy people in all parts of the city, going to individual homes in some cases, exposing herself to great danger. She also worked for the mission church and school. She played the organ, taught Sunday School, and conducted services.

Hamilton was in what we now know as Turkey during the Armenian genocide (1915-18). When Hamilton was in Aintab, she lived through three massacres, including one in which the perpetrators came to the gates of the hospital to destroy all the inmates.

In 1915, the city of Aintab near the Syrian border had 40,000 Armenians who were Christians, and by 1922 there were only 3,000 remaining. The Turks forced the Armenians to march into the desert to the east, leaving them with no supplies and no protection. They took their belongings and some were put in concentration camps. Historians estimate that as many as one million Armenians died in the genocide and 500,000 left Turkey.

In the middle of the genocide, in October 1917, a report from a returning missionary described Hamilton’s worth to the Turks. The Turks worried that she would leave when the United States entered the Great War. Though the U.S. never fought in Turkey, we allied with the Turk’s enemies. Hamilton was not in good health as she had contracted typhus in 1915 and never fully recovered. The other missionaries tried to get her to leave, but she pledged to stay until the war ended. Some city residents tried to get her to take on citizenship so that she would not be expelled from the country. Though she stayed, she was persecuted, having stones thrown at her when she visited patients and finally she took a soldier with her when she made home visits.

Her hospital for women and children was transformed during the war into a military hospital with ties to the Red Cross. Hamilton preached Christianity to the wounded soldiers. At the same time, she had to listen to soldiers boast of their role in the genocide.

Hamilton also cared for 12,000 refugee women and children. The missionary described Hamilton sewing a woman’s nose that had been almost cut off. The patient then went on to become one of the best workers in the hospital.

On February 16, 1920, the New York Times reported that The American Committee for Relief in the Near East said that Americans had escaped from several towns where Armenians were being massacred. Armenians were destitute and many were sick and wounded. Hamilton evacuated from Aintab and was safely in Marash with 16 other missionary workers.

In that same month, Hamilton came back to the US and spoke before the Smith College Club where she argued that the U.S. had to take action and move beyond its ignorance and indifference. She claimed that the U.S. was better suited than either the French or British to carry out this military action.

President Woodrow Wilson tried to help sustain the Armenian state which was established in 1918. Opposition from the Republican Party and a lack of troops led to the Armenian state collapsing in November 1920.

Hamilton left Turkey for 18 months from August 1920 to February 1922 when the Turkish government carried out more massacres against the Armenians and her hospital had to be abandoned. At that time, she went to Beirut where she ran an orphanage for 300 children.

Throughout her 37 years abroad in Aintab, Turkey and in Lebanon, Hamilton remained a member of the First Congregational Church in West Hartford. She wrote letters to church members and received gifts of money and supplies at Christmas from the church’s Bible School. When she came back to the United States on furlough, she addressed missionary meetings, not just at the First Church, but at churches throughout the area.

Hamilton’s work, which started more than 120 years ago brought one of the first woman physicians from the U.S. to a country where she witnessed mass murder. Her motivations, probably to live the life of an independent woman, and to play an important medical role in a place where she was “other” and could have more power, may not be too different from young people’s motivation for mission trips today. Hamilton’s Christian missionary zeal sets her in a different era, but her idea to use her expertise to help those in need still holds sway today.

William H. Hall and our “Highest Duty”

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, February 2010

My friend, Trinity Professor Jack Dougherty, and I were recently debating when it was that West Hartford began promoting its successful public schools as a selling point to attract families to settle in West Hartford versus surrounding towns. He held that West Hartford did not start competing for residents via their schools until the late 1950s. It seems like the commitment to good schools as a part of the civic virtue of the town, however, starts earlier.

William H. Hall (1845-1934), In 1872, at age 27, Hall was hired as principal of the old West Hartford High School, as shown in this 1875 photo. As the town’s first historian, he wrote a history of West Hartford, and published it in 1930, when he was 83 years old. At this age he was still involved in the schools, teaching local history for an hour per week to 5th and 6th graders at larger elementary schools in town. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

A look at the schools’ history begins with one-room schoolhouses. By 1902, the town had consolidated its nine school districts. Adolph C. Sternberg was the Acting School Visitor (head of schools) until 1896. He was served in the General Assembly from 1895-6. He felt that the schools needed more skilled supervision than he could give them, and he arranged to have the Secretary of the State Board of Education, Prof. Charles D. Hine, assume the supervisor position until 1897. When Hine realized it was more than a part-time job, he hired high school principal William H. Hall and the position transformed into the Superintendent of Schools. Hall held that position for 25 years until 1922 when he was 77. Upon Hall’s retirement, Lloyd Bugbee, the Principal of the West Hartford High School, a youngster compared to Hall, stepped in and served as Superintendent until 1947.

There is some early evidence of pride in the town’s schools. In 1902, William H. Hall, wrote “A Historical Sketch of West Hartford” for the dedication of the new red brick Town Hall, in which he praised the school system. At the time, the town had about 3,000 residents and was still a farm town. Hall was the Superintendent and a town historian in his own right, and he used his speech to glorify and celebrate the town.

He related the history of West Hartford from 1679 –- the first settlement –- to 1902. He believed that to understand the present, the citizens needed to not only know the past, but also understand their indebtedness to those who came before them. From 1713 to 1796, according to Hall, the Ecclesiastical Society of the West Division supported five schools up and down Main Street. He argued, “our fathers made very wise and generous provision for the educational interests of the community,” an expression of civic virtue.

From 1796 to 1855, the state gained a role in school governance as the General Assembly established a School Fund with the proceeds from the sale of Western Reserve lands in Ohio. A state-mandated School Society managed the funds for the West Division (West Hartford). By 1885 the schools were consolidated under the town’s new government.

Hall believed that the successful town residents who went to schools here demonstrated how good the schools were. Hall listed Noah Webster, Theodore Sedgwick who became Speaker of the House and a U.S. Senator, Titus Hosmer, a member of Congress, John Woodruff a judge in New York State, Benjamin Burr who helped establish the glove industry in Gloversville, New York, James Seymour, banker, Ebenezer Belden, printer and publisher of the first daily newspaper in New York City, more than 25 ministers, including Lemuel Haynes, a “colored boy” born here and who became a successful minister in Vermont. His examples of success seem to be individuals who gave back to their communities. Hall concluded:

We certainly have good people, good homes, good churches, good schools, good laws, good officials, good roads and good public buildings. But none of these are so good that they do not admit of improvement, and it should be our constant aim to attain to that which is not simply better, but best.

Let us not forget, however, that our highest duty, our noblest endeavor, our grandest opportunity and our true success as a community are to be found in such use and improvement of all these advantages and blessings as will result in the training of our children and youth in character and life so that they may most worthily serve God and their fellowmen in their day and generation.

Hall’s priority to make educating children the “highest duty” led to big changes in the school system. As the population grew, so did his plans for the school system. West Hartford was on the cutting edge when it opened two junior high schools in 1922, only the second and third junior highs in the state. Ground had already been broken for the new high school.

When Lloyd Bugbee became Superintendent in 1922, he requested that the State Department of Education do a report on the state of West Hartford’s schools. State Commissioner A. B. Meredith spoke at Webster Hall in the Noah Webster Library, invited by the Democratic Women’s Club to deliver his report. William Hall presided over the meeting. While Supt. Bugbee praised his teachers, Meredith and the State Board criticized the town for falling behind in both its buildings and its student achievement.

Meredith pointed out the physical needs of the schools and the changes needed in the course of study. There was a desperate need for a new high school, and yet the cornerstone had already been laid. Three of the seven elementary schools were so crowded that they ran double sessions. Again, Bugbee quickly responded with the Beach Park School (1926), Morley School (1926), an eight-room addition on Smith School (1926) and Elmwood School (1928). As for student achievement, the elementary students were performing only slightly above average; the State Board felt Bugbee could expect more. Perhaps Bugbee was willing to receive the criticism and used it to his advantage to galvanize the public to support his building program.

Still, there were some anecdotal signs of good results. On February 11, 1924, the Hartford Courant headline read “West Hartford’s Schools Praised: Men Prepared there Do Well at College, Say Dartmouth Authorities.” Dartmouth College sent several commendations to the Superintendent “commenting on the splendid preparatory training received by graduates of the West Hartford Schools.”

Though its schools were not yet used to sell houses by 1925, the town leaders started to define civic virtue through caring about its schools. They did not yet provide the draw to the town that they would in the next 15 years.

Superintendent Lloyd Bugbee

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, March 2010

West Hartford’s population growth between 1910 and 1920, led to an emergency situation in the schools, as buildings were not constructed fast enough to keep up with the growing student population. At the same time, the administration couldn’t keep track of its teachers. Superintendent William H. Hall led the school system through this growth (1897-1922), but when he retired in 1922, his successor Lloyd Bugbee, jumped into action.

In 1922-3, Superintendent Bugbee asked the Connecticut State Board of Education to survey West Hartford’s schools. The 151-page survey provided Bugbee the outside pressure to accomplish much of what he may already have known needed to be done. As soon as the State Board published its survey, several towns asked for copies and the state department printed 350 copies for its own distribution.

Lloyd Bugbee was hired in 1917 at age 27 as the principal of West Hartford’s high school. He grew up in Vermont, graduated from Dartmouth College, and then did graduate work at Columbia Teacher’s College. When Bugbee took over for the 74 year old Hall, it was truly a changing of the guard.

Until 1917, William H. Hall served as both principal and superintendent and had no staff to support him. Between 1913 and 1922, high school enrollment jumped from 105 to 343. While the population grew about 84%, the high school enrollment grew over 300%. Under Hall, two new junior highs were built and construction began on the high school. Bugbee was known for both building the infrastructure and developing an innovative curriculum in West Hartford.

Bugbee had to address the overcrowding in the elementary schools. With a school population that almost doubled from 1910 to 1920 to 1,769 pupils, Bugbee had to find places for the students to attend school. Ten classrooms were so crowded that they had to go on double sessions.

Under his administration, 12 new schools opened. He added courses in the high school that included aeronautics, driver education, and nature study. And Columbia University’s Teachers’ College named the new elementary curriculum exemplary.

The State Board of Education Survey, published in 1923, recommended improved supervision along with a building program which entailed spending about $100,000 over two years. The Survey called for hiring a supervisor for the elementary schools while Bugbee would supervise the junior and senior high schools. The Board of Education hired that person. The survey called for establishing special classes for adult education. And, as schools began to take on more responsibilities than just the 3 R’s, the survey recommended West Hartford hire a school physician, dental hygienist, and director of physical education right away.

Bugbee used the report to act. In 1923, West Hartford began its adult education division by offering its first three classes at the Elmwood School. Also, Bugbee promoted the West Hartford public schools outside the town. He took on leadership roles in the region as well. In his second year as Superintendent, Bugbee chaired the fall meeting of the Connecticut State Teachers’ Association held at Hartford Public High School.

West Hartford excelled in writing elementary school curriculum. By January 1926, Teachers College at Columbia University commended Superintendent Bugbee on the new elementary curriculum. Bugbee, his elementary school supervisor Ethel Merriman and a committee of teachers designed a course of study in history and geography judged to be one of the top 25 out of several hundred submitted to the college.

West Hartford pioneered in foreign language instruction. In April 1926, Bugbee addressed a New York City conference of eastern junior high schools to describe West Hartford’s introduction of foreign languages in the eighth grade. Students spent one-semester learning word origins, six weeks of Latin, and five weeks of French, to learn the principles of words. The curriculum introduced all students to the study of language in an innovative way. Bugbee encouraged the implementation of exploratory courses for eighth graders.

The Beach Park School also helped put West Hartford on the educational map. With five acres of land donated by T. Belknap Beach in 1925, the Beach Park School was the first in West Hartford to be built in a park-like setting. Beach wrote in the deed that no trees could be cut except for park purposes. The architecture of the building was more like a home than an institution. The colonial structure and color scheme for the three-classroom building, finished in 1926, were a departure for school buildings. A national education journal wrote an article about the school and educators visited from across the country.

Bugbee’s idea was to develop a school with the “happy atmosphere and freedom which the preschool child enjoys at home. It is a place where children may live together working, playing and learning as they might do in a happy family.” The building enhanced the teachers’ abilities to reach these goals. In 1929, Bugbee wrote “This home-like and livable atmosphere is probably one of the most outstanding evidences of progressive education.”

Teachers and administrators in Connecticut viewed Bugbee as a leader. He was a regular at the state teacher’s convention. In 1927, he was elected by 200 state delegates to represent Connecticut at the National Teacher’s convention in Minneapolis.

The Hartford Courant praised Bugbee in 1929 for urging the town to buy school sites before the town was ready to build and before neighborhoods were built. Bugbee claimed this was a policy established by William H. Hall. In 1929, the town bought the site on Park Road on which Sedgwick School was built. It also bought two properties in the northern, undeveloped section of town. The Courant article claimed “Superintendent Bugbee is considered invaluable to the town by many officials because of his acute vision in school matters.”

By 1930, in his ninth year as Superintendent, Bugbee’s reputation continued to grow. Franklin E. Pierce, state supervisor of secondary education commended Bugbee for following through with a ten-year survey following high school graduates. Pierce commended the survey for following not just students who went to college but also those who went straight into the workforce. Bugbee used the survey to ascertain what advantage students got from the West Hartford.

While the Connecticut State Department’s Survey in 1923 was critical of the school system, Bugbee, at the young age of 32, used it to legitimize many of the changes he wanted to bring to the town. Bugbee’s leadership put the West Hartford schools in the vanguard in Connecticut and the nation.

The League of Women Voters: Building Leaders in a Democracy

Originally appeared in West Hartford Life, June 2002 and October 2010

In February 1920, six months before ratification of the 19th Amendment, suffragists founded the League of Women Voters on national, state and local levels to crusade for “the success of democracy.” The founders of the non-partisan organization calculated that their job would take five years to teach the 20 million new women voters how to participate in a democracy and then they would disband.

The West Hartford League formed two years after the state and national Leagues and just three years after women won the right to vote. In 1920, West Hartford’s 9,000 residents lived in a suburb. There were still farms in the north and south ends of town, but the percentage of people in town who worked in farming declined. Some residents worked in West Hartford factories like Spencer Turbine or Whitlock Coil and Pipe, while many of the new residents took the trolley to insurance jobs in Hartford. The new houses built on farmland attracted middle class families, in which wives left the workplace upon marriage and often had time for, and an interest in, volunteer work.

The West Hartford’s League of Women Voters, established in 1923, has been a vibrant community organization dedicated to building leadership and “a better informed, more intelligent electorate.” The League’s longevity and success is based on several factors. They have specific goals based on civic engagement in a democracy, they build a sense of community within the organization, and provide many different types of activities for members, taking advantage of their strengths and abilities.

Women’s political roles expanded in the 1920s and the League reflected this. At the same time, many women held onto their traditional roles in society and in the organization. The sense of community built by the League played a large role in the League’s success. Through the mid-1920s, many of the League meetings worked around an elegant tea. Attendees dressed in their best clothes including hats and white gloves. At first, luncheons were held in the Masonic Hall, and by the late 1920s, luncheon meetings were held at the West Hartford Country Club (today Buena Vista) and the Hartford Golf Club. The Hospitality Chair was one of the most important women on the Board. These luncheon meetings catered to women who, though they did not work for wages, maintained a concern about the political world. This sense of community, fostered by these luncheons, gave the League staying power.

The activist women realized that socializing did not do enough to educate new voters. League member Charlotte Lundgaard led a drive to register more voters. Only 23% of the West Hartford electorate voted in 1922, and the League took it upon itself to target West Hartford’s 2,200 women voters who had not registered. The League bought 1,100-penny postcards, at a cost of $11 and sent them to eligible voters. On registration day in 1923, they set up a tent in the center of town, provided babysitting, and served coffee. League President Mrs. E.E. Stiles, said that the league would organize a “motor corps” to drive women to the Town Hall to register to vote. The drive netted 940 new voters. The movement was non-partisan and the idea was to “waken the women to their civic responsibilities.”

At the local election in mid-March 1924, West Hartford residents cast twice as many ballots as ever before in West Hartford’s history. Lundgaard entered a contest with The Woman’s Home Companion magazine on behalf of the League and won the $150 prize! The magazine editors knew only 26% of newly enfranchised women had exercised the franchise and they encouraged groups to share their success stories. Lundgaard wrote in her application for the national award that even if not a single voter had been registered, “the labor of that enterprise would have been worth it to ascertain what League “team power” was. Our organization worked as a man that day, with magnificent esprit de corps.” Lundgaard’s definition of success in this case was working like “a man,” despite the fact that all the work was done by women. In this sense, Lundgaard bought into the male idea of success, but did it all with women power.

Once the women were registered to vote, the League offered classes to educate new voters. Members needed to know about state and local issues and chairs of committees took on the task of educating their members. In the 1920s and 1930s, the League sponsored “Citizenship Schools,” which organized speakers to talk about the problems of the day. Both men and women attended these “schools” and the League provided childcare for mothers with young children.

Those who came to the March 1924 meeting heard Mr. Christopher M. Gallup, president of the West Hartford Chamber of Commerce, talk about West Hartford elections. Gallup, an officer at Travelers Insurance Company, and a one time chair of the West Hartford Democratic Party, was one of the first advocates in West Hartford for the Council-Manager system of government and he helped make West Hartford the first in Connecticut to adopt this system in 1919. Gallup and his wife lived on Steele Road, and Mrs. Gallup served as Secretary on the Board of the League. She became involved in the national League and traveled as a delegate to several national conventions in the 1920s.

In 1924, the League sponsored an exhibit entitled “The Fair Tariff.” In June 1925, they spent $1.85 on a Child Labor Study Guide from the national organization. They set up study committees about town government, education, and planning and zoning. These committees provided leadership roles for women who had for so long been kept out of the public sphere.

League members also raised money. In the 1920s and 1930s, the League used rummage sales, bridge parties, tea dances, and yearly dues to raise money. Committees formed to organize each event.

The League served as a training ground for women who got involved in politics. In 1929, Grace (Mrs. William) Honiss, the Vice President of the League ran and won election as the first woman to the Town Council. In that same year, she was elected chair of the board of directors of the West Hartford Library. In 1931, the school board appointed Mrs. Edward Lorenz as its first woman. Louise Duffy was appointed to the school board in 1938. The Board was appointed well into the 1950s. Before entering formal political office, all three women were longtime members of the League.

This wide-ranging, bipartisan organization offered numerous opportunities for women to get involved in the political world. Though many historians see the 1920s as a time of frivolity and flappers, characterized as the “Roaring Twenties,” many women continued to pursue the reforms that had started in the Progressive Era before World War I.

Anne O’Hare McCormick, the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize in journalism, for her work as a foreign correspondent for the New York Times, was the inspiration for a pen and ink drawing of a woman with a broom on the front cover of the 1945-6 West Hartford League of Women Voters pamphlet. The League, and McCormick believed that women should find careers and not be intimidated by men. They also believed women would help clean up politics.

In this organization, women educated themselves about political issues, learned from speakers at meetings, and studied national and local political issues. They enjoyed the social activities like tea dances and fancy luncheons at the country club and used them to build support and community. For others, organizing fundraisers gave them a means to develop a sense of worth and a sense of community. For still others, the experience with the League led them into the male dominated world of politics. League women went with a broom in their hands to clean up abuses of power as they saw them, while they tried to broaden the electorate and wholeheartedly support democracy.

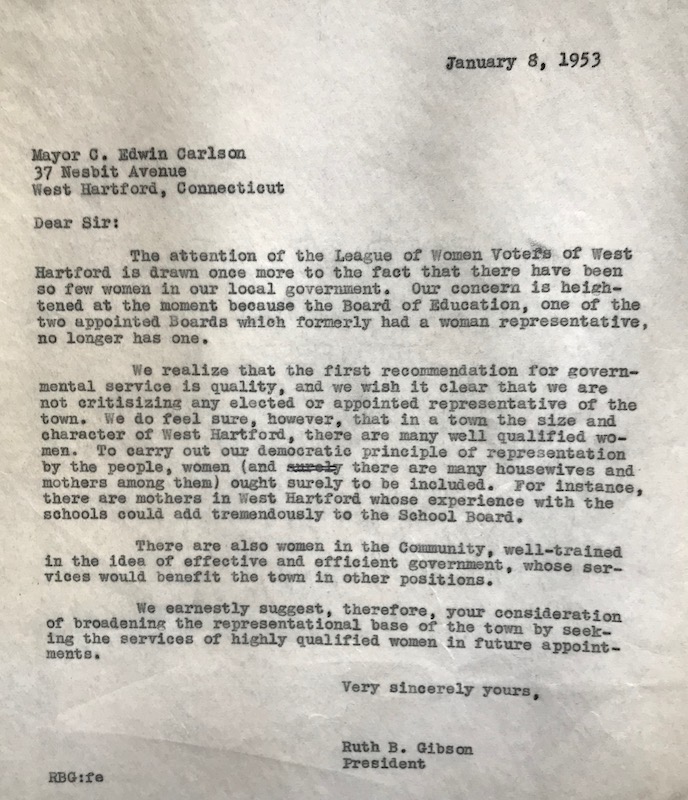

In 1953, the League continued to push for women’s representation in local government. League President Ruth B. Gibson advocated for a woman to be appointed to the Board of Education. Source: “Your Vote Your Town Folder,” Greater Hartford League of Women Voters Papers, Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

Ruth Dadourian: A Stalwart for Justice

June 2018

Connecticut is often seen as the “land of steady habits,” with a conservative base that did not take to political change very readily. This held true for the Connecticut state legislature’s lack of ability to pass the woman’s suffrage amendment until after it became a federal amendment in 1920. But in other ways, women like West Hartford’s Ruth Dadourian (1892-1983) led the way for rights for women and justice for many others.

Ruth and her husband Haroutune lived much of their adult life in Hartford. In 1950, after Prof. Dadourian retired from Trinity College, they built a house on the Old Mill Pond north of the American School for the Deaf, and moved to 177 North Main Street, West Hartford to live out their retirement years.

Ruth McIntire was born in Italy in the late 1890s, and by time she graduated from Radcliffe in 1912, she was an accomplished linguist knowing Italian, Russian and French. She took part in her first woman’s suffrage demonstration when she was a student at Radcliffe College. There she met her husband, H.H. Dadourian who became a math professor at Trinity College in the late 1910s.

Ruth Dadourian’s first job was as a publicist for the National Child Labor Committee. In 1918, Dadourian wrote a pamphlet for the National Child Labor Commission decrying child labor. She found children as young as five working in the beet fields. Dadourian’s main academic interests were in child welfare and labor, public health education and labor laws.

When she first arrived in Hartford, she didn’t know many people but brought with her a desire to work for justice. While shopping downtown, she discovered the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association headquarters. She walked in and was “greeted with open arms,” a young woman interested in suffrage. She said, before she knew it, she was on the board of the organization.

Dadourian actively participated in the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association. When the Connecticut Woman’s Party, led by Katharine Houghton Hepburn, split off from the group in 1917, there was not the same rancor between the two groups as existed on the national level. In fact, Dadourian argued that “the Woman’s Party was really the spearhead and then we (CWSA) could follow through… The more outrageous they were, the better off we were.”

When women won the right to vote, Dadourian knew the battle for women’s rights was not over. She knew that the campaign had not just been to win the vote, but women had to continue to educate both suffragists and their opponents, and make policy makers know women would actually participate in political matters. In 1920, she said, “Even if we wanted to, could we possible escape the responsibility of victory?”

On March 21, 1921, Dadourian appeared at a hearing for House Bill No. 722, providing for the extension of the personal tax to women. Assessing this $2 tax collected each year by each municipality would show that women had “equal franchise rights” with men. If men failed to pay, they were imprisoned. Male legislators seemed to think it would not be the right thing to imprison women so were hesitant to pass the bill. Dadourian, the legislative secretary of the Connecticut League of Women Voters, favored extending the personal tax to women, but suggested exemptions, possibly in the case of mothers, to demonstrate that women were, in fact, equal.

In 1923, Ruth Dadourian was instrumental in starting the West Hartford League of Women Voters. She served as the director of the state league from 1926 and then became its president and lobbyist from 1934 to 1935.

On March 19, 1927, Dadourian wrote a letter to the editor of the Hartford Courant in support of women serving on juries. She argued that hundreds of women from all over the state supported this bill and packed the hearing. The lobbying effort was thorough. Urban and rural women testified from every part of Connecticut. Women who served on juries from surrounding states testified as did judges, lawyers, and prosecuting attorneys. Dadourian wondered if those against the bill believed that Connecticut women were “inferior in intelligence and ability to women in the twenty-one states where they are now serving.”

There were those who believed that the state should hold a referendum to poll women on whether they wanted to serve on juries because the opposition claimed they did not. Dadourian argued “our representatives are elected to use their best judgment in enacting wise legislation for the State.” In 1927, Connecticut had 15 women in the legislature, more than in any other state and women had every other legal right men had.

Dadourian and her husband also weighed in on international affairs. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the United States did not recognize the new revolutionary government. In 1930, she and her husband, a native of Armenia and fluent in Turkish, Armenian, Russian and French took a seven month study tour to Europe. When they returned, the Dadourians advocated for diplomatic and commercial recognition of the Soviet government, which finally came in 1933. They praised the Soviet people for their “enthusiasm and willing sacrifice… in their efforts to attain the Communist ideals.”

Mrs. Dadourian argued that before the war, two-thirds of the Russian population were illiterate. Just 13 years later in 1930, only one-third was illiterate. The government built hospitals and nurseries for women workers. The Dadourians saw that the Russian Soviet people sacrificed greatly for the changes made by the Communist government. The institutional changes that impressed the Dadourians the most were communal apartments with communal kitchens to free thousands of women from kitchen drudgery; parks for children, and a penal system, which the Dadourians believed did not use retribution. One wonders if they felt the effects of the McCarthy questioning 20 years later.

During the New Deal, Ruth was supervisor of the Division of Women’s and Professional Projects of the Works Progress Administration in Connecticut. During Governor Wilbur Cross’s tenure, the Connecticut League of Women Voters presented the state with a memorial tablet commemorating 31 women who according to Dadourian, “built up public opinion which resulted in women winning the franchise.” Isabella Beecher Hooker, a nine-year-old great-granddaughter of Isabella Beecher Hooker unveiled the tablet. You can still find it in the south corridor of the Capitol.

In 1935, Dadourian chaired the Connecticut Committee for Ratification of the Child Labor Amendment. (She must have known Louise Duffy who supported it as well.) Dadourian wanted the National Recovery Administration Codes, which banned child labor in many occupations, and was set to expire in 1935, to continue through a constitutional amendment. This law was never passed.

In 1934, both Ruth and her husband Haroutune appeared in a publication called The Red Network: A “Who’s Who” and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots. In this book she and her husband were listed under a group called “communist recommended authors,” a group officially endorsed by the Soviet Union Review, an organ of the Soviet government in Washington D.C. The pamphlet publicized their leftist leanings, probably based on their glowing reports of the Soviet Union after their travels.

In 1941, Governor Robert Hurley (a West Hartford resident) appointed Dadourian to the Board of Trustees of the University of Connecticut. Just two months later she was appointed field representative to assist the chair of the woman’s divisions of local defense councils and volunteer offices in planning and carrying out their activities. She served as chair of the statewide conference for women in defense.

Bob Stewart, retired Trinity professor of mathematics, remembered Ruth Dadourian after she had a stroke. She invited guests over for dinner. When it was time for dinner, it took Dadourian about ten minutes to make her way from the living room to the dining room, but according to Stewart, everyone in the room knew enough not to ask her if she needed help. She was very strong willed and had few soft edges, remembered Stewart.

But people enjoyed being in her presence. They knew what she stood for and they wanted her on their side.

Louise Day Duffy

June 2018

If you enter Duffy Elementary School on any morning, you will hear the Duffy “pledge” over the loudspeaker:

As Duffy citizens,

we show respect,

demonstrate compassion,

and take responsibility for our learning and our actions.

That is a motto that Louise Day Duffy could embrace. Her matronly portrait that hangs in the hallway of Duffy Elementary School belies the active life she led as an advocate for students, the poor, women, and those without a voice. In 1949 when the Board of Education voted to name an elementary school after Duffy, they showed their support for these moral ideals and her belief in public service.

Louise Day Duffy (1885-1973) joined many politically active women in West Hartford by breaking the mold about what was acceptable for women in the first half of the 20th century. Her leadership in our town is remarkable.

When Louise Day was 11, her parents moved from Avon with their seven children to Raymond Road; her father helped develop Frederick Rockwell’s Boulevard with the median down the middle between Trout Brook and South Main Street. Her father’s contracting business, P.R. Day & Sons included two of Louise’s brothers and they built a number of homes on Raymond Road near Boulevard and on Westland Avenue. Her father served as Justice of the Peace, and as the first chairman of the Business Men’s Association (later the Chamber of Commerce). Louise Day’s father figuratively and literally built community. Later they moved to a house on Outlook Avenue when the area had a 10 hole golf course.

Louise Day graduated as the valedictorian from the West Hartford High School in 1902 in a class of four students, the first entering class at the school. She went on to study at Smith College, graduating in 1906. She taught for one year at Windsor High School until Superintendent William Hall persuaded her to come teach English and Math at her alma mater. She taught and coached there for four years, from 1908 to 1912.

The basketball photo shows a 26 year old Louise Day as the coach of one of the first girls’ basketball teams at the West Hartford High School. Just as today, her athletes had long hair secured to keep it out of their face as they played on the court. Their knickers, stockings and neck ties, variously displayed, showed the individuality of each of the young women who built the team. Though no one in the picture is smiling, they exhibit a sense of determination and pride, and respect for their coach, qualities that Louise Day carried through her life.

Coach Louise Duffy sits with her West Hartford High School girls’ basketball team in 1911-12. Source: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society.

Between 1912 and 1915, Louise Day left West Hartford to be secretary to the superintendent of the Horace Mann School in New York. When she came home, Louise married Ward Duffy (1891-1961), the year he graduated from Trinity College. She met him at the West Hartford High School where he was a 1911 graduate. Duffy’s family lived at 208 North Main Street in the John Whitman house. Ward’s father, Frederick (1864-1928) had been a high school teacher in upstate New York, but looked for a place to live where he could farm. He found their house along a section of Trout Brook which was called Whitman Falls. His wife Elizabeth grew up on a 400 acre farm just south of the Canadian border. Duffy “farmed from the book,” and grew a herd of Jersey cattle and sold milk. He ran for office and served on the first Town Council in 1921. He later became editor of the Hartford Times.

Louise and Ward Duffy had five children: two boys and three girls. Louise ran the household and raised her children (born between 1917 and the mid-1920s). She was one of the founders of the Hall High School Parent Teacher Association in 1924 and one of its first presidents.

Duffy got involved in the political world, first in the Connecticut Woman’s Suffrage Association with Katharine Houghton Hepburn, and then, in 1923, at age 38 she helped found the League of Women Voters in West Hartford. The purpose of the League, was to get women politically involved in voting and running for office.